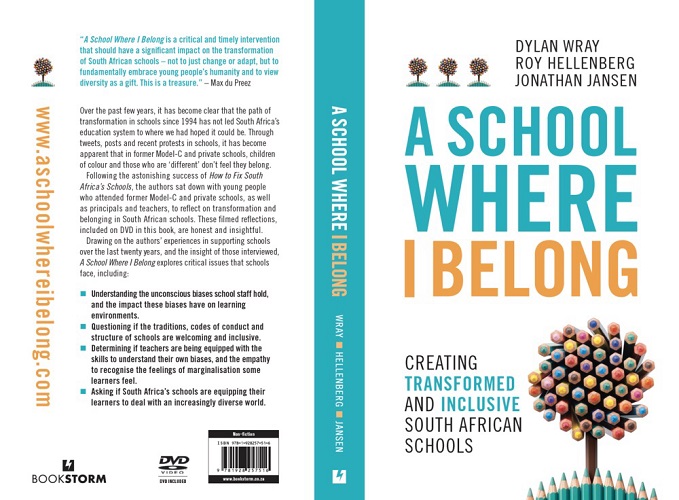

A School Where I Belong, written by Roy Hellenberg, Dylan Wray and Professor Jonathan Jansen, was launched at the Cape Town Central Library last week. A book that attempts to challenge unconscious bias in schools and create schools where all learners belong, ASWIB also leads workshops for schools’ three primary groups: learners, staff and parents. All three men have decades of experience in education in a myriad of capacities. Professor Jansen currently teaches at Stellenbosch University and Hellenberg and Wray, former high school teachers, have committed to ASWIB on a full-time basis.

In collaboration with Shikaya – a local organisation that supports teachers and school leaders to help ensure young people leave schools thinking critically as well as engaged in public life as democratic citizens – and Facing History and Ourselves – an American organisation that helps students learn about hatred and bigotry so they can stop them from happening in the future – ASWIB engage in hands-on work to tackle the issue of inclusion in schools. They ensure that the school communities they engage with both ask and grapple with difficult questions and Hellenberg asserts that unconscious bias is one of their primary focuses.

“We’ve been doing this for just over two years and we’ve worked with enough schools to be able to make an educated assumption of where the impact is. I believe the impact is really around the educators and leadership of the school and for many of them we’re not talking about overt racism where they are calling kids monkeys and the k-word. It’s the unconscious bias, that’s the most debilitating and destructive issue that we’ve had to contend with and making people aware of that and how it plays out in schools has been the biggest impact that we’ve had to this point in time,” said Hellenberg, a former teacher at Groenvlei Senior Secondary, Silverstream Secondary and Rondebosch Boys’ High.”

“At least 60% of the teachers at the schools we’ve gone to had never thought about their actions as being, in any way, bias against other racial groups. And of course that would be true because it’s unconscious, it’s implicit bias, it’s in the tone of voice, it’s in the smiles or lack of smiles, it’s in the proximity that you stand to the person, how many times you ask them questions, all of those things. If you’re not even aware of it, why would you deal with something that doesn’t exist,” said Hellenberg.

This year, the department of basic education was given a budget of R246.8 billion after the minister of finance explicated that it formed one of three national priorities for the year. However South African schools are not only critically underperforming in maths, sciences and literacy, but, according to Wray, are reproducing many of the ills the country is plagued with, like racial bias. Wray, the former head of history at Wynberg Girls’, stressed that schools are the ideal place to address these biases.

“I think after Pretoria Girls’ stood up and let their voices be heard, it was clear that definitely model-C and private schools have been believing that they’re doing things right and that there are no problems. What Pretoria Girls’ showed was that at the vast majority of schools where integration happens, and we know that’s in a minority of schools in South Africa, but in those schools where it does happens there’s been an overarching bias towards assimilation to the school culture. Very little conscious effort has been put into ensuring that schools actually adapt to the changing dynamics and demographics of their learner-body. Schools haven’t done that. I think schools for a large part have felt immune to what was happening around in society, while businesses, for example, have been forced to adopt employment equity positions and they’ve had to embrace, even if unwillingly,” said Wray, founder of Shikaya.

Although businesses, as alluded to by Wray, can get away with a lack of sincerity in creating and promoting equitable employment and hiring options, schools hold the very future of the country in their hands. ASWIB’s research has shown that not only is racial integration occuring in a minority of schools but also often in majority white schools – which make up most of South Africa’s private and infamous former model-C schools. Upward social mobility has seen many who were excluded from these schools during apartheid attempt to get their children into them. However, these are not the only schools where integration happens, as Hellenberg explained that he’d conducted workshops at a previously coloured-majority school in Cape Town that has seen significant growth in its black student population. What is clear is that people have been schooled in racial silos and the results thereof are desperately in need of undoing going forward.

“It doesn’t help when a school is becoming increasingly racially diverse but the core group who controls the school is still feeding a westernised culture to the students. Then you’re turning black people into ‘coconuts’ or ‘better blacks’ and it’s not fair to them and it’s not fair to their parents. Transform the space and make everyone, staff and learners, feel comfortable in the space,” said Sizwe Malinga, who attended an all-boys school in Durban.

Jansen, who was not at the event, adds further expertise to ASWIB’s ambition of creating transformed schools. “I have always worked with schools struggling to deal with race and racism,” the former University of the Free State Vice-Chancellor said, “this time we decided to put our knowledge and experience into book form so that many more could benefit from listening to other schools who are ‘doing change’ and perhaps benefit from our own journeys as change agents in and for schools […] This is the first book that takes on issues of race, identity and difference head-on in former white schools using the voices of students, teachers and leaders in doing so. There is no doubt that the crises around these issues that erupted at schools like Pretoria Girls, Sans Souci and St Johns, among many others, have inclined the more privileged schools to sit up and take notice that change either comes to you in a disruptive way or you can lead for change and anticipate and deal with some of these pressing issues.”

Should you wish to arrange a workshop at your school or purchase a copy of A School Where I Belong, you can find a copy here.