It is young people, in India, as in South Africa, who may be our last hope. As the fervour of revolt spreads, it is as if history has begun to take shape. And those who decry the apathy of youth should take note. In the ongoing collusion of big capital and the State, it is young people who have picked up the baton of protest, argues AZAD ESSA.

In Delhi, the story begins with a protest. On February 9 student activists mark the trial and execution of a Kashmiri Muslim man charged for his role in the attack on India’s parliament in 2001. Afzal Guru’s case has divided opinion, with human rights activists questioning the judgment.

But many on social media and some prominent Indian TV journalists were quick to brand the protests as anti-national, and what followed was an unprecedented police crackdown on students of Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU). The protests were squashed thoroughly.

And they were squashed, with impunity.

The attempt to muzzle truths and criminalise speech with the label of anti-India is not new. India has been repeatedly accused of repressing free speech, its new government nurturing extreme Hindu nationalism. Under Narendra Modi, this nationalism has turned toxic.

ABVP planning a massive rally today to protest against ‘anti-India activities’ of communist brigade in JNU pic.twitter.com/gV7u9lKHe1

— CNN-IBN News (@ibnlive) February 24, 2016

Ari Sitas, sociology professor from UCT currently on an academic visit to JNU, described India as entering “a dangerous phase”. Palagummi Sainath, former rural editor of The Hindu, told JNU students that while they were allowed to be shocked by the attack on freedom of speech, they were not entitled to surprise.

“It is the criminalisation of dissent that is what you are fighting. It is to make criminals of dissidents. That is the process you are fighting … Welcome to the rest of India,” he said.

The cataclysm of dissent demonstrated at JNU over the past month is no coincidence. If dissent was to make its way to the urban centres, it was always likely to find its way between Ganga Dhaba and the admin block. It’s where urban dissent in India has always lived. Dissent is the smog that clings on to the cheap maroon pullovers and navy woollen scarfs of the chai wallahs (tea sellers), academics and future conspirators in this iconic talk shop. But India has since changed, or shown its true self. Dissent is unwelcome. This is a country slowly becoming attuned to unwelcome posts disappearing off Facebook pages and celebrated writivists like Arundhati Roy facing treason charges for little more than disturbing words.

While the outrage has moved to other campuses across the country, JNU remains under potent scrutiny. In the eyes of the ruling right-wing BJP and the RSS, a paramilitary organisation modelled on European fascist parties of old, this university has managed to resist their national Hindutva project for far too long. Considered the last bastion of progressive thought in the country, Hindutva ideology has found it difficult take root here. And it’s not the first time student refusal to accept the state narrative has been labeled as anti-national.

This deviance, as Sitas puts it, is all too familiar to South Africans hit by a wave of student-led protests over the past six months.

“The student insurgencies are different. In India, it is to defend something; in South Africa, it is to change the status quo,” Sitas said.

In fact, the rage in JNU and its immediate rebuttal in the main is the story of a two-step, performed incredulously by a generation of students across the globe. From Delhi to Addis Ababa to Durban, students have recognised that a grand collusion of capital and state is in the process of destroying their futures. The status quo is untenable.

In India, the rage manifests itself against caste inequalities, misogyny, communalism, and rising Hindu authoritarianism that hides itself under an agenda of “development” and “Make in India” or “India shining”.

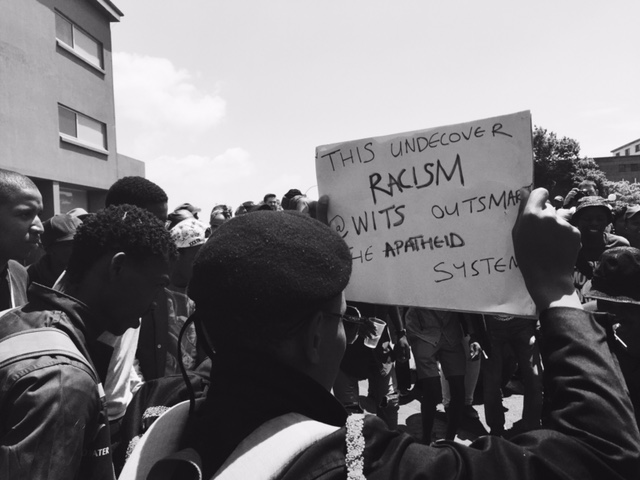

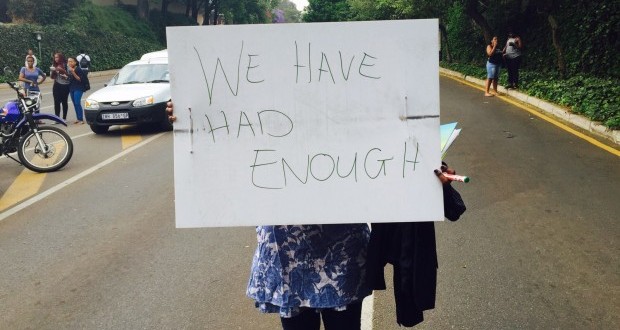

In South Africa, the rage seen over the past six months over tuition fees and outsourcing, is a refusal to accept continued economic apartheid that excludes the majority of black South Africans under the guise of the “rainbow nation” and “non-racialism”.

“Most South Africans should now be able to accept that our country has been muddling through a superficial peace,” Sisonke Msimang said last week in the Daily Maverick.

The numbing legacy of colonial constructs and endless apparitions of progress in both India and South Africa remain obstacles to progress.

The student movement, born from #RhodesMustFall to #FeesMustFall has become the biggest critic of post-apartheid South Africa, not unlike the critics of liberalisation in India.

Freedom’s children, the born-frees, are adamant that economic apartheid end as political apartheid, which had to be debated, ultimately unraveled. Whereas the Freedom Charter of 1955 promised “The Doors of Learning and Culture Shall be Opened!”, and the ANC said it would be so, education is still the territory of the rich. But dissent is not just restricted to education fees – students are demanding a decolonisation of syllabus, language, and the very ways in which knowledge has become a tool to keep people from thinking.

Take this account by Kalim Rajab, who describes using part of his time as a scholar* raising money to refurbish the statue of Cecil John Rhodes statue in Oxford. Rajab acknowledges that Rhodes “inflict[ed] some of the deepest psychological scars on my country’s psyche”, but suggests it’s time to “let go” of the past.

Whereas Rajab, like so many others, chose to decorate a statue (even as he talks about letting go of the past), today’s Mandela Rhodes scholars in Oxford are facing up to their dead benefactor, recognising historical torment, and asking tougher questions about the future. It is this type of shallow readings of #RhodesMustFall movement (despite their shortcomings) and post-liberalisation India that has been borne out the “rainbow nation” and “Shining India” myths propagated by those obsessed with maintaining their privilege.

Besides, the very laws being used to silence dissent in India today are the same British laws used to criminalise dissent of India’s first revolutionaries. Mahatma Gandhi himself was in jail for six years because of articles he wrote for a weekly journal “Young India.”

Rajab can talk about “letting go”, but that’s easy if you’re thinking only about yourself.

Rise of majoritarianism

A culture of dissent has descended upon the young, who feel disempowered by their representation, angry over trapping inequalities, frustrated by their subservience of their parents, and yet empowered by their decision to lead themselves. The stage is new, and they will at times deviate. And it must be so.

The rise of majoritarianism politics in India has left the country back-pedalling into a dangerous and abysmal pit of intolerance. By October 2015, some 35 poets and writers had returned their national awards to protest the move to shape secular India as per the whims and whims of the Hindu majority. In November, despite its zany reference to global investments, the New York Times Editorial Board said the “plain truth is that India is being riven by hatred and held hostage to the intolerant demands of some Hindu hard-liners”. The quelling of dissent is part of this patronage to the new India.

Despite the attempts of South Africa’s National Student Financial Aid Scheme (NSFAS), parental wealth remains the real guarantor of a child’s access to higher education, and this means that it is still the black child who must face the brunt of the past: systematic exclusion and poverty created by 300 years of colonialism and apartheid. If education is sold as the escape from subservience, then education cannot be exclusive, or inaccessible. It is also only the first stage of a greater struggle.

“We live like pigs, in Alexandra, in Langa. We have no land. That’s the first thing we need to do. Expropriate the land so we can bring back the dignity of our people. There is no one who can have dignity and confidence if you do not own a piece of property,” EFF CIC Julius Malema said at the Chamber of Commerce debate on the economy.

And the response?

In South Africa, on discussion forums across the net, privileged white and brown voices talk of “inconveniences”. The lower middle classes are squeezed, but they are certainly not the ones with the biggest gripes. On some of South Africa’s most elite campuses, private security have been deployed to police black rage. Court orders and interdicts and vague charges now guard the university’s honour from “disruption”. In Durban, or Johannesburg, or Pretoria, the mainstream media continues to peddle state labels of “illegal” protests, “disruptive” and “trespassing” students. Following protests for the dismantling of Afrikaans as a medium of instruction at the University of Pretoria in February, the government’s retort was that “fringe elements are trying to destabilise the institutions.”

I honestly do not understand Min. Blade Nzimande. Why not just deal with the students and let the “fringe elements” reveal themselves?

— Ntsika Scott (@MnrNtsikaScott) March 1, 2016

In India, the government and its media pander to the state narrative that describes dissent as “anti-national” or “anti-India”. Holding an opinion at variance with those deemed acceptable by the establishment, especially when it comes to the story of Kashmir, is terrorism. Pankaj Mishra says that the Indian state’s “multi-pronged assault on JNU students [showcased how] a long, savage but largely invisible war on India’s margins is finally coming home”.

And how.

Featured image by Lizeka Maduna

Editor’s Note: A previous version described Kalim Rajab as a Mandela-Rhodes scholar when in fact he was an Oppenheimer scholar at Oxford. We regret the error.

![JNU FMF collage [slider]](https://www.thedailyvox.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/JNU-collage.jpg)