South Africans are excessively familiar with the history of Mahatma Gandhi for many reasons.

The historic train incident that happened at a railway station in Pietermaritzburg, South Africa is described as Gandhi’s “aha” moment. He gave up all worldly attachments to become the half-naked politician that preached the ideals of Satyagraha.

The greats like Madiba, Barack Obama, Martin Luther King all quote the great Gandhi. But how great was Mohandas?

Over the past two years, I’ve experienced a sense of confusion and hurt that clouded my historic belief in the man we know in South Africa as “Bapuji”.

The persona of the great soul that Mohandas took on assumed the right political outfit by preaching the official national culture of India, which remains exactly the same today. Indian national culture is casteist, vegetarian, spiritual and xenophobic. Gandhi claimed this as humanitarian, peaceful, and moral charisma by further invoking a mythologised father of Indian national identity.

If one had to ask me if I would hang up a portrait of Gandhi at home or one of Madiba, I would choose the latter.

My belief is that Madiba gave us South Africans the long awaited freedom from the oppressors of apartheid, NOT Gandhi. Recent calls for statues to fall in South Africa have included Gandhi; Ghana has also refused to honour him.

I turned a blind eye too long to the accusations as I was not ready to accept that Gandhi was/is a bad person. The shock of knowing that Gandhi used the term “kaffir†struck a chord of anger in me. The word “coolie” also stirred an equal amount of anger.

Using the word “kaffir” enraged me.

You see, that word resonated with me in relation the atrocities that blacks in South Africa had to endure. When one keeps an open mind over the mysticism around Gandhi, one will learn that he played a political game on both sides of the equation. I would even go as far as stating that Gandhi’s strategy continues to live on in politics of today.

The late Amichand Rajbansi is an example of Gandhi and also was branded a sellout when he became part of the tricameral system and invoked Gandhi and Pandit Nehru to justify his participation in the tricameral system.

Another problematic fact about Gandhi is that he fought for controlled environment settings for Indians during the colonial era. Racial segregation was a belief that Gandhi strived towards within the bubble of the British Raj (British colonial rule) of South Africa. His strategy worked to some degree to shape the politics of India and also here in South Africa.

One of the first struggles in South Africa that Gandhi fought for was the implementation of the third queue at Post offices such that Indians did not need to use the queue designated for “kaffirs”.

The other act of treason against black South Africa, Gandhi cheered the British war effort during the “Bambatha Uprising“, urging Indians to send care packages to the soldiers “in order to express their sympathy.” He suggested these packages include “fruits, tobacco, warm clothing and other things that they might need.” In his words, “It is our duty.”

Later, his life mission in South Africa was not to campaign for the human rights of Indians but for the business class of Indians.

Why is it so important to challenge the ideals of Gandhi?

While the concept of Satyagraha developed, the Gandhi camp saw the value of political strategy inside this beautiful struggle policy that could elevate their position in the status quo to above South African blacks. This was Gandhi’s logic that Indians of the “business class” were above the “savages”.

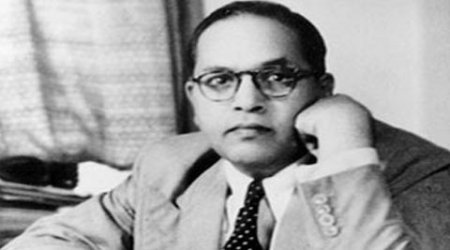

But back in India, three years prior, the Mahad Satyagraha by politician and social reformer B.R. Ambedkar occurred to allow untouchables to use water in a public tank in a village called Mahad.

“The Mahad satyagraha (non-violent movement) is comparable to Mahatma Gandhi’s Dandi march and Martin Luther King’s Selma march,” said Anna Bhau, a Dalit campaigner. “It represents the collective articulation of our rights and our decision to assert them but in India, the word satyagraha means Gandhi.”

But every Dalit in Mahad remembers Ambedkar’s contribution and his memory stays in images, books, flags, banners, and even brochures of life insurance policies that carry a small picture of the marginalised people’s icon that wrote the Constitution.

Gandhi never supported Ambedkar as this broke all logic of the caste based strategy, but he found it fitting to use the element of passive resistance to drum up his political status as the great Mahatma.

In July 2014, Arundhati Roy stirred outrage that the generally accepted image of Mahatma Gandhi was a lie. Speaking at the University of Kerala, Thiruvananthapuram, she also called for institutions bearing his name to be renamed. The Booker prize-winning author’s comments rekindled a long-running historical argument over Gandhi’s views on caste and catapulted hot debate.

The assassination of Gandhi and his namesake legacy over the years was a blessing in disguise, but it wasn’t enough.

The Dalits of India are still contained in a caste-based policy. They are considered untouchable; they remain the “kaffirs” of India but they are rising. Their legacy of caste-based politics of India is reaching a tipping point and Modi’s Gaurakshaks (cow patrols) will be lynched soon.

As the history of Gandhi unfolds, some will deny some truths and some will attribute that later in his historic life Gandhi had changed his position and stance on politics of caste. The call for #GandhiForComeDown might be harsh but it is a truth we need to address.

I am of the opinion that South Africans of Indian descent should not claim that we sent back a Mahatma to India. It seems we sent back a monster.

Sources

1. Annihilation of Caste is an undelivered speech written in 1936 by B. R. Ambedkar, an Indian who fought against the country’s concept of untouchability.

2. Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi, Vol. 5, p. 259, June 9, 1906

3. The Doctor and the Saint by Arundhati Roy

4. Nathuram Godse: Why I Killed Gandhi

5. What did Mahatma Gandhi think of black people? Washington Post

This piece was originally published on the Naufal Khan’s blog and is republished here with permission.