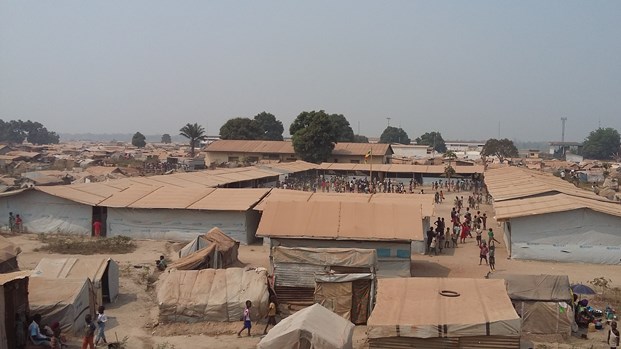

Over 20, 000 refugees who have fled violence in  the Central African Republic (CAR) still inhabit the Mpoko refugee camp at the Bangui airport. DONAIG LE DU describes what life is like for the 6,000 children who attend daily classes inside the camp.

“Most children here really have a bad mindset. You know, they have heard a lot of gunfire, so now they keep drawing weapons, and all they want to do is fight and shoot guns. I feel bad for them, because their former life was nothing of the kindâ€.

Veva, 14, is sitting with her parents in front of their “home†– a small tent, made of tarpaulin, which can hardly accommodate their small mattresses and few belongings. This is all they have left.

In December 2013, when violence shook Bangui, Veva and her family fled their house in town and sought refuge in Mpoko, the capital’s international airport, which was quickly becoming Bangui’s largest camp for internally displaced people. At the peak of the crisis, 130,000 people gathered there, their makeshift huts spilling onto the tarmac. Now Mpoko is still home to over 20,000 people – those who have nowhere else to go.

It is a desperate place. During the dry season, dust is everywhere. During the rainy season, the whole camp becomes a field of mud, and despite people digging trenches, the water always finds its way inside the tents. A few families live in wrecked planes, and the airstrip turns into a soccer field in between plane landings and take-offs.

Veva’s only occupation is going to school. She is one of over 6,000 children attending daily classes in the camp. UNICEF, with European Union funding and the help of the local NGO REMOD, has set up temporary learning and child protection spaces on the site.

“I love school,†says Veva. “It’s my future. If I do not go to school, what will become of me?â€

Every morning, Veva puts on clean clothes and joins her classmates under the tents. She will be sitting for an exam next month, hoping to make it to high school.

“School makes me forget all the bad things, all the bad memoriesâ€, says Veva.

Her face lights up when she explains she wants to become an administrator. “I see the administrators here on the IDP site, they work well. So I want to be able to manage an administration, and school will allow me to do that, because I learn a lotâ€.

Of course, the road will be long before Veva can get a degree in administration. But in the future, she says, she will need to get a good job, because she wants to help her parents.

“I ask God to keep mum and dad safe, because they work hard to protect me, so that I can succeed until today.â€

Veva’s father, Léon, a former accountant now unemployed, is worried about the behaviour of many of the camp’s children. So he keeps a close eye on his daughter and her friends. Most of the schoolteachers in Mpoko are themselves displaced and live on site. They have to deal with violence on a daily basis.

“Sometimes children come to school with knives, they put them in their schoolbags,†says Chancelle Willy Bono, the headmaster. “So every morning we search their bags, and sometimes we find things. When we do, we take the child aside, in my office, and we talk to him, we try to put him back on the right track.â€

UNICEF and partners have begun giving teachers training on psycho-social support, so they can deal with traumatized schoolkids, some of them formerly associated with armed groups, some of them orphans, all of them having seen and experienced things no child should go through.

Enabling displaced children to go to school is not only a matter of giving them an education, of course. It is also about restoring a sense of normalcy and hope, in the bleakest of environments.

Over 30,000 children are currently attending emergency schools throughout the Central African Republic. The hope, of course, is to have them close their doors soon. But with 10% of the population still internally displaced, there is very little chance of this happening anytime soon.

“Of course I want to leave this place,†says Veva, eyes brimming with tears. “I used to have a nice house, with five bedrooms, a terrace, and gardens all around. That house does not exist anymore, it has been completely destroyed by the fighting. You know, life is not easy here. I don’t like it.â€

Watch UNICEF’s interview of Veva’s here:

Donaig Le Du is a former journalist and current chief of communications at UNICEF Central African Republic.