The topics of violence, non-violence and questions of what “legitimate†violence looks like have marked discussion about the #FeesMustFall protests.

The general public – whether student, official, parent or academic – has been calling for students to practise non-violent tactics in their call for free education. This falls in line with SA’s recent history, the legacy of Nelson Mandela and, as Sisonke Msimang points out, the compromises of 1994 to ensure that there would be no bloodshed.

In turn, students have challenged us to see that violence means more than physical harm to individual or property – that the poverty, discrimination, exclusion, neglect, inequality and the many issues most of us have come to accept as “normal†in South Africa, are in fact pervasive forms of violence. Their actions, the students often argue, are responses to violence.

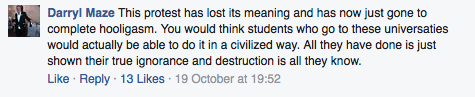

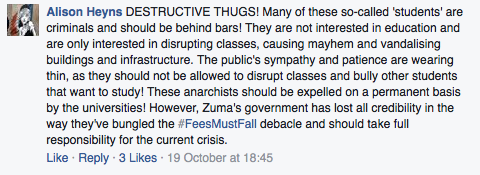

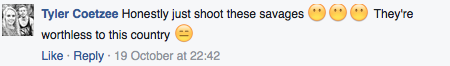

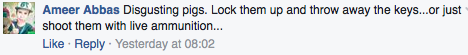

Yet, separate from this legitimate debate is another predominant narrative relating to violence. A vile, dehumanising narrative that casts students as lacking intellect, and only understanding destruction.

This narrative is not unfamiliar. While it makes no reference to race, the idea presented follows the same mindset we’ve become used to encountering in SA. It’s the tired story of black people as naturally inclined to violence, “stupidity†and indirectly being responsible for the downturn of the country. It’s an interesting mixture of fear of the swart gevaar, “things were better during apartheid†nostalgia and a deep resentment towards the ANC.

Racism aside though, this narrative is also intellectually lazy. It tries to take the complex issue of violence and make it a one dimensional problem. Take this recent video from Times Live showing UCT protesters assaulting a security official.

Now according to a strand of armchair analysts, the issue here is simple. The students are unreasonably violent and need to be dealt with as they’re clearly a destructive force in SA. The video, in fact, proves what they already knew.

This tendency to interpret new information as confirmation of what you already believed, is what’s called “confirmation biasâ€. It’s dangerous because it hampers our ability to learn beyond what we think we know – it stops us asking critical questions.

For example, if many of these armchair analysts weren’t lost in their own confirmation bias, they might have attempted to look further into why the security guard was singled out as is seen in the video. A little bit of digging would have shown that the security guard who was attacked was the same man who used excessive force on one of the students earlier that week.

According to students, the security guard was specifically targeted because he grabbed a woman by her hair from the library she was illegally occupying, to the point that her braids were forcefully ripped out.

@helenzille same terrified security guard! I’m guessing you support woman abuse as long as it fits your agenda of demonising black students pic.twitter.com/LuT5m1feQY

— Azania eNsundu (@ReturnOurLand) October 20, 2016

While this does not justify the violence met on the security guard – it does give context and provide understanding to why the students attacked him. It also casts doubt on the notion that students are irrationally violent. Of course, the jury’s still out on the second guard who had a rock dropped on him and was hospitalised as a result – yet, again, it’s lazy and telling to assume such action is due to some inherent deficiency of protesters.

There’s no denying that student protests have been marked with violence – from all sides – but it’s very rarely, irrational violence. A lot of the time it’s motivated by an internal sense of justice, or retribution, or emotionally backed, but that’s still reasonable. This is an important distinction to make.

It’s the difference between the caricature of the unthinking, barbarian mentioned earlier, and acknowledging a conscious actor driven to, or choosing violence, as a tactic – for reasons we may or may not agree with. The former is akin to the describing someone as a wild animal – and that dehumanising line of thinking is dangerous.

When one makes the distinction – when one sees that it’s possible to strongly disagree, be outraged over a situation, without having to rob people of their humanity – the conversation then moves to the legitimate debate of non-violence and questions of ethical tactics. We can then begin addressing issues of the unequal use of force in protest situations, what legitimates the use of violence – if anything at all – and how to move forward in addressing the currently existing social injustices in SA. Maybe, if we’re brave enough, we might even look to what causes people to resort to violence.

This is the kind of discussion South Africa needs to be having. Not the nonsense below. It’s 2016 for God’s sake – it’s time we grow up as a society.

![[slider] mcebo-dlamini-wits-feesmustfall-protests-slider](https://www.thedailyvox.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/Mcebo-dlamini-wits-feesmustfall-protests-slider.jpg)