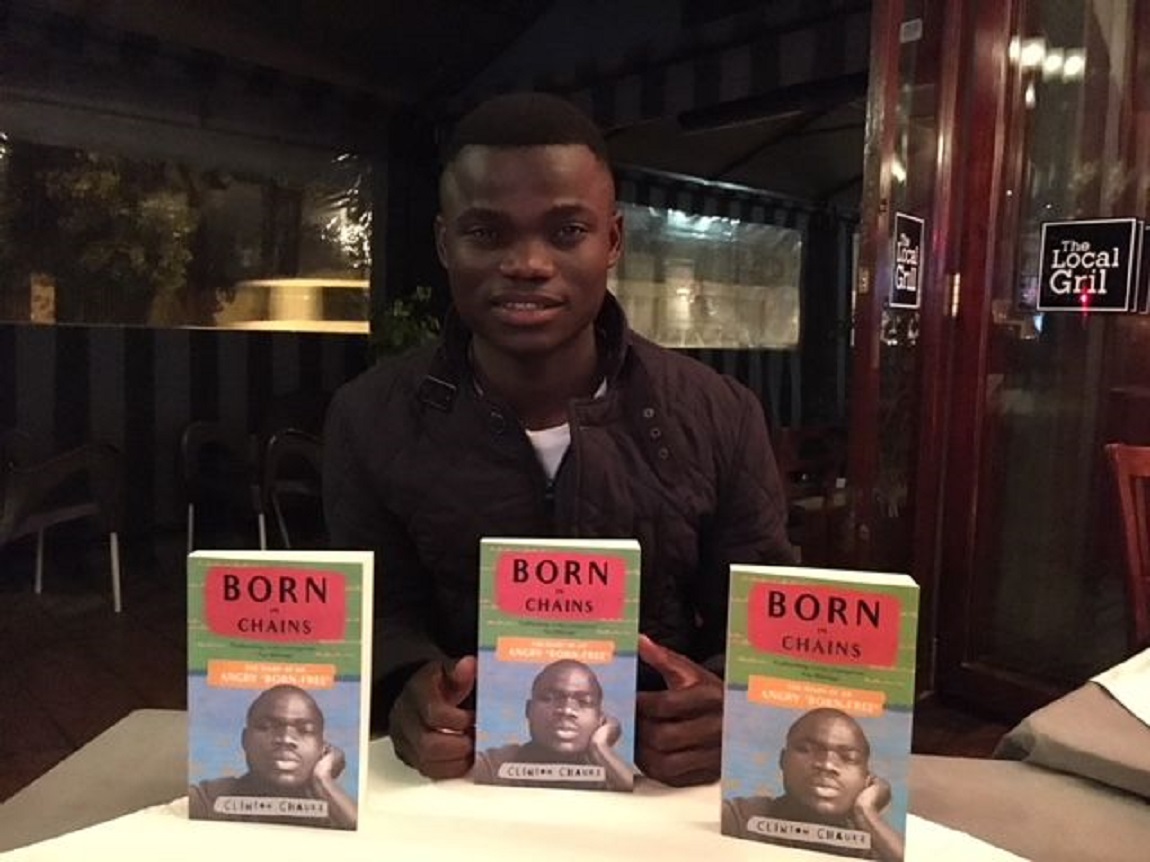

There’s a lot of things Clinton Chauke would describe himself as: social critic, fierce debater, Pan-Africanist. But despite being born in 1994, one label he flatly rejects is that of “born free”. Chauke is also the author of Born In Chains: The Diary Of An Angry “Born Free” where he writes about what it’s like to be young and black and poor. The Daily Vox chatted to Chauke about his book.

Why did you write this book?

I wanted to share the story of growing up as a black folk in South Africa. It’s the story that’s common but never shared. It’s a personal memoir. I aimed to find identity for myself, but I also tried to open that room for other young people as well who could see themselves in my story. I’m telling my story but at the same time I’m telling their story of life as a South African. It’s my story but it’s also their story.

Tell me about the title of the book Born In Chains: The Diary Of An Angry Born Free?

The title was inspired by Professor Tinyiko Maluleke, who is at the University of Pretoria, when he was reviewing the book of Malaika wa Azania and his title was something along those lines. Malaika wa Azania is this young kid, she was born free but still living in chains. I was like wow, that resonates with me. I chose to use that title. Then as I was writing the book I realised it was more of a diary entry. Then I said I would subtitle it The Diary Of An Angry Born Free.

Your book is the antithesis to the myth of the born free in South Africa. Why do you say you are born in chains?

As a born-free, I am optimistic. But the truth is, some of us live in poverty. In my book, I’m not trying to romanticise poverty. I’m not trying to romanticise the conditions that I grew up in. It took years to build the system that we are in right now. When we get political freedom as black people, the project won’t make us economically free overnight. We need to be careful with that, and keep the vision. In my book, I’m trying to say that poverty is real no matter how much the government or anyone who is optimistic would like to say we’ve moved forward. The inequality is there. The poverty is still there. Even the system of discrimination is still there. We need to talk about these things and then maybe we can find a way of solving them.

What has writing this book taught you?

Writing the book has taught me a lot of things. It has taught me to be vulnerable, and allowing myself to be a human being without bottling emotions or hiding any weakness that I may have. As human beings, we are all flawed. As much as we’ve got strengths we’ve also got weaknesses and in my book I talk about my weaknesses. In doing that, I’m trying to show that I’m a human being – I’m relatable. I’m not larger than life. It taught me humility, not treat people with respect and dignity because we’re all human before anything else.

How was your writing process?

The process has been an emotional one. I wanted the book to be a motivational book but then I realised everybody can say work hard and so on. I needed to be specific so I turned the book into a memoir to let the reader draw out the inspiration and the motivation. For the reader, I wanted them to be inspired unconsciously by my text. I wrote the book over the course of two years, from the day that I began writing up until the last day I was changing it.

What has the response to your book been so far?

The response has been great so far. They have welcomed the story. Some may not agree with the things that I wrote in the book, but they appreciate the fact that I wrote and voiced my opinion. Most of the people are more motivated their own stories because I’m just a normal South African. I just had a story and I wanted to share it.

As a young South African, do you feel like your voice is valid? Are the voices of young South Africans valid?

As young people, our voices are valid. Even though the people in power, they tend to not fear our voices. If you check history, it’s been young people who have carried us through the darkest times. If you talk about 1976, the Soweto Uprising, it was young people. In 2015, the Fees Must Fall generation, it’s young people. As young people, our voices are being heard against all odds.

What is your hope for the youth of South Africa?

I hope that the youth get involved in politics. One way or the other, they must be politicised. There’s no such thing as not being interested in politics. That’s also a kind of politics that says, I don’t care about you so go kill yourself. I advise South African youth to be more interested in politics so they can realise how they can contribute. It might be doing stand-up comedy, it might be singing, it might be acting. Once you are aware of the political power that you hold, you are bound to fight for social justice and change. That’s how our country can move forward.

So, are you saying the youth don’t have to join a political party to get involved in politics?

Well, some of them must join political parties as well because we need young people there. There are old timers sitting in the Parliament. I know they are not fans of that institution but they must use their voices in all the different ways available to them.

Some people might say that you’re too young to write a memoir or a book. How do you respond to that?

If you are a young person, you’ve got the whole world waiting for you. Even if you make mistakes, you can still get up. You still have time to bounce back. This is an experimental stage. Whatever you want to try out, you should try out. If you fail then you realise in your 30s and 40s that you tried to write a book but it wasn’t accepted by publishers. Or you tried to make music but your career didn’t work out. You must live life with no regrets. Have fun. If you want to give this freedom a chance, we must do whatever it is we are free to do. And what a wonderful time it is to be young, black and talented.