On Wednesday, France’s new president, Emmanuel Macron, caused a wave of excitement when he appointed a cabinet that was made up of 50% of women. The cabinet is also politically diverse, with people chosen from both the left and right. (None, however, are from the far-right National Front, led by Marine Le Pen, who Macron beat in the election.)

The Daily Vox team looked at women’s political participation around the world to see how it stacks up.

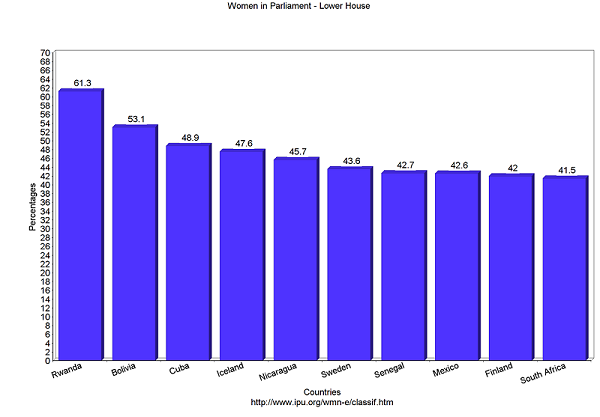

In recent years, several governments have tried to improve gender representation in parliaments.

Rwanda requires at least 30% of all parliamentary seats to be held by women. Since 2010, Bolivia has required an equal number of male and female candidates on the candidate lists for elections.

In South Africa, women make up 41% of all members of parliaments and 35% of our ministers are women.

However, sheer numbers don’t always translate to equal power. South Africa has several female ministers but several of them them have been accused of supporting patriarchal policies. A case in point would be the tepid response to increasing violence against women from Minister of Women in the Presidency, Susan Shabangu.

The same can be seen in Rwanda, which despite having more women in politics, still has many patriarchal policies. One example is a policy to reduce maternity leave from three months to six weeks, which was widely criticised by women’s rights activists in the country. Efforts to implement national policies regarding gender equality have also been met with resistance.

In Bolivia, several women’s empowerment organisations involved in policy change and lawmaking have made gains in political representation. Still, in 2012 when an attempt was made to pass a law protecting women from political violence based on gender, it still wasn’t passed in parliament despite the high numbers of women represented. And while the law was later passed, implementation is still sorely lacking.

A United Nations report on women in parliament notes that most women ministers oversee social sectors, such as education and the family. Macron however has appointed a female defence minister. (For the record, South Africa also has a female defence minister in the cabinet.)

There’s a good reason to include more women in government – impact. This is seen most clearly at local government level, according to the same report. In India’s local government, women-led councils oversaw 62% more drinking water projects than men-led councils. And in Norway, a direct relationship was found between the presence of women in municipal councils and childcare.

While the percentage of women in national legislatures is usually the standard measure of a country’s achievements in women’s political participation, disparities still exist. These discrepancies directly affect women’s political rights and can restrict rights in other areas.

The UN Women says that to ensure better policy formulation for gender equality there should be:

- more women leaders and representatives in parliaments;

- laws and policies in place which promote gender equality;

- better policies for women; and

- leadership programmes for women at grassroots levels

In El Salvador, UN Women helped mobilise women from advocacy groups, parliament and the country’s supreme court to create laws to make public institutions more gender-responsive.

And in Moldova, where there weren’t enough women district councillors and mayors to make women’s political agendas a priority, the country formed an organisation – the Women’s Network of Mayors and Local Councillors – as part of the Congress of Local Authorities to help make gender equality a priority.

It is encouraging to see Macron’s new women-friendly cabinet on paper. However, more work is required for meaningful women’s political participation. Moreover, there’s a need for a women-centered national agenda.