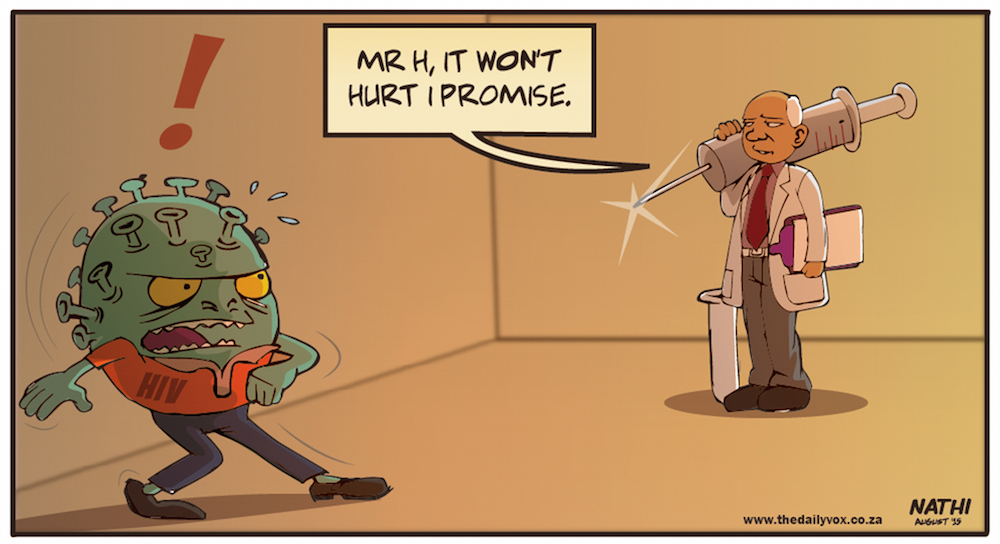

It might come as a surprise to you but doctors are sometimes terrified of their patients. DR THOMAS GRAY explains why.

Many people associate doctors with the notorious “injectionâ€. Parents in particular love the association: “Behave or else I’ll take you to the doctor for an injection!†For a doctor, needles are a part of daily life. They come in different shapes and sizes. The types we use are generally hollow and used for intravenous access, allowing us to deliver medication or draw fluid.

Doctors may be a dull bunch, but we’re cool enough to identify our needles by colour. The big grey or orange ones are huge, used mainly for trauma patients who have lost a lot of blood and are in need of life-saving fluids. The green or pink ones are workhorses, used for most adult patients. The blue ones are smaller and made for smaller and younger patients. The yellow ones are tiny, and used for newborns and young children.

We encounter other potentially hazardous materials on a daily basis – suture needles used to sew together bodily tissues; blades to cut into skin and body cavities; and, of particular importance in South Africa, the knives, pangas, broken bottles and other sharp objects that often present lodged in the bodies of patients who walk into trauma units.

All of these – needles, blades, and bleeding injuries – put us at risk of one of the biggest daily fears of every healthcare worker in the world: HIV.

Why are doctors at risk?

HIV is a virus transmitted by mixing of bodily fluids. The virus alters the affected person’s immune system, making them more susceptible to infections and illness and further hindering the body’s ability to deal with it. The advanced stage of the disease known as AIDS (Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome) can be catastrophic.

Most of those who have served in South African public hospitals during the last decade or two have been witness to the HIV epidemic.

Thanks to the advancements made in the treatment of the disease, most people with HIV can now live a near normal life. But a cure for the virus still remains elusive and fear and anxiety surround the mere mention of the disease.

The nature of our work puts us in direct contact with body fluids and the virus, turning such fears into a daily reality. An accidental needle prick or a splash of blood in the eyes can be all it takes to transmit the disease to a healthcare worker on the front lines of medical care.

Fortunately research has shown that the danger of accidental exposure can be largely mitigated with the use of post exposure prophylaxis (PEP). This involves having the person who was exposed to the disease start on a course of antiretrovirals (ARVs) as soon as possible after exposure to reduce their chances of contracting the disease. Unfortunately this is a bit more complicated than it sounds.

All doctors have, at some point, been the victim of a needle stick or an eye splash. Often it happens at 3am when you’ve been working for way too many hours and your judgment is severely altered; or it happens with students or interns who are still naïve to the fact that patients often jump when poked with a needle.

RELATED: Why doctors do what we do

Let me take you through the experience.

The prick or blood splash usually happens when you least expect it. It only takes seconds for you to let your guard down, whether it’s forgetting to slip your goggles down your forehead before taking a peek into a wound or doing the last few sutures on a routine wound closure.

It’s quite a surreal experience, especially the first time. Your first instinct is deny it: “I don’t think the needle tore through the glove,†you tell yourself, “I don’t think it quite went into my eyeâ€.

Protocol dictates that we irrigate the wound or the eyes as an initial precaution. This is usually when you notice a small blob of blood extruding from your fingertip, and the reality hits you. Panic sets in and you begin making frantic calls to your nearest colleague.

Once you’ve managed to come to your senses, so begins the laborious process involved in PEP – opening up a hospital file, getting a colleague to draw blood from you and from the patient for testing, and getting your starter pack of ARVs.

This is where things can get a little interesting.

The HIV test

Now most of us are fairly certain as to whether we have the virus or have the potential to have the virus (HIV is spread mainly through sexual activity). But there’s always a significant level of anxiety involved in doing an HIV test. This anxiety goes to a whole new level when one is married or involved in a relationship.

Not all HIV tests are foolproof, and sometimes they can give you what’s called a false positive result. This means that the test says you are HIV positive when in fact you aren’t! Further, more specific (and expensive) tests, if done, can later refute the false positive result.

But just imagine the shock of being given a false positive result after an already very stressful experience – and the awkward conversation that must then be had with your spouse.

The ARV experience

If the patient’s HIV status is confirmed as positive, one has to complete 28 days of ARV treatment. These aren’t your average Panados or antibiotics. These drugs have serious side effects, which can vary from person to person. The most common are:

- severe nausea and vomiting. According to women, this puts morning sickness to shame.

- damage to your liver. This serious complication can land you in hospital, glowing in the dark with skin as yellow as a banana.

- damage to your pancreas. In addition to the kind of stomach pain that will leave you crying like a baby, you have the risk of developing diabetes.

- damage to your kidneys. There’s no better way of appreciating that golden stream than when it’s gone.

- psychiatric problems like depression and insomnia.

Enough said.

Once you’ve been on ARVs you’re always reluctant to go back on them. Just the thought of them makes you sick, which is why you’ll stop at nothing to avoid them - a luxury not available to those who have confirmed HIV.

At the same time, it’s a very humbling experience. Getting first hand experience of what a patient has to endure every day of their life can only instill more empathy and understanding in a doctor.

While research into a cure continues, the problem of HIV and the risk to healthcare practitioners remains a worrying reality.

Please share your experiences with us below in the comments section.

![Pediatric doctors review cases [wikimedia commons]](https://www.thedailyvox.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Pediatric-doctors-review-cases-wikimedia-commons.jpg)