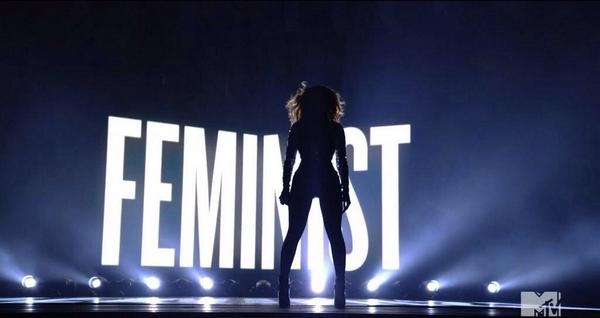

Feminism, the “other F-wordâ€, is making a comeback in mainstream media. Over the last year many (female) celebrities were bombarded with the question “Are you feminist?†and Beyoncé’s “Flawless” collaboration with author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, which questioned ideas of what a feminist should look like or behave, caused a stir. But questions about the exclusion of women of colour from feminist debate remain.

This is what inspired filmmaker, writer and gender activist Paromita Vohra to pen a brief, yet necessary, open letter to white feminist filmmakers, concerning the white messiah complex underlying the controversial documentary India’s Daughter, directed by the BBC’s Leslee Udwin.

“What is the reason you are still making such primitive ‘documentaries’? Is your patriarchal society, with its belief in objectivity and poor re-enactments … also editing out leading questions, stifling your expression?†she begins.

The documentary, which concerns the brutal gang rape and murder of medical student Jyoti Singh in Delhi in 2012, was banned in India, purportedly because it would incite further violence against women. It was broadcast earlier this month in the UK.

Vohra argues that Udwin makes “essentialist explanations about other societies to undermine feminist solidarity and political engagement†through her narrative.

She isn’t alone in her criticism of the documentary. Kavita Krishnan, the secretary of the All India Progressive Women’s Association, who has been leading protests since the rape happened in 2012 found that the documentary treads the thin line of respectability politics.

“In the film we are told she had permission from her parents to go out that night. I wonder why the filmmaker thought this was important. After all she was an adult woman. Why should she seek permission? Would she have been any less of a victim had she not taken permission, had she been unapologetic about having the right to go out?†she told NPR.

Udwin’s pointing out that Singh sought permission to go out plays into stereotypes of “good girls†vs “bad girls†and also implies that her brutal rape would have been legitimised by Indian society had she not sought or been granted permission.

Tanvi Misra,writing for the Atlantic, lists narrow perceptions of Indian women – as modest, virtuous and virginal – and the narrow focus on Singh’s role as a daughter as among the film’s flaws.

“Jyoti, the person, was probably much, much more when she was alive,†she writes.

Vohra’s open letter, and the comments from Indian feminists and others who have distanced themselves from the documentary while standing in solidarity with Indian women’s struggles for justice and equality, stems from growing frustration with a feminism that fails to recognise the intersection of race, class and sexism, or what is referred to as intersectionality.