South Africa’s education system is considered to be one of the worst in the world. A 2015 study by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development ranks South Africa 75th out of 76 countries in terms of mathematics and science. With Africa projected to experience an upsurge in its youth population over the coming decade, there are growing fears that the country is not doing enough to prepare scholars for the jobs of the future.

According to the United Nations Children’s Fund (Unicef), Africa’s growing child population will require the care of at least 11 million skilled professionals by the year 2030. This includes the 5.8 million skilled teachers needed to help educate this growing youth population and 5.6 million more medical practitioners to care for them.

But with less than half of the 1.2 million pupils who enrol in grade one making it to grade 12, questions must be asked about where South Africa will find the doctors and teachers needed to care for the young people who have yet to be born.

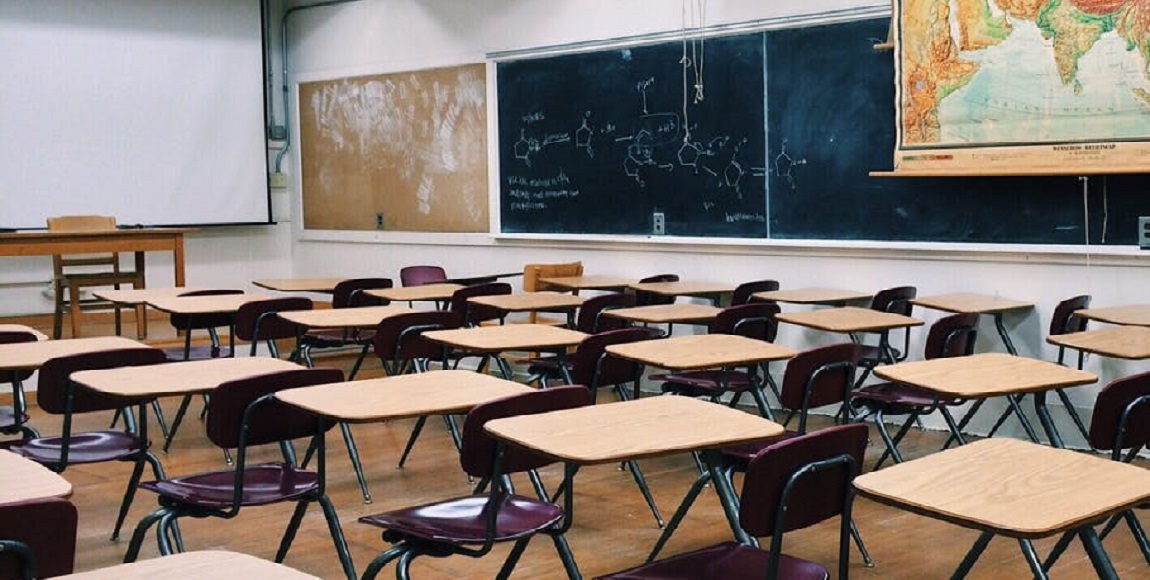

South African schools continue to replicate the apartheid-era divides among schools, which saw white schools well resourced and black schools neglected by government. Formerly black-only schools are still poorly resourced today and offer a poor quality of education compared to formerly white-only schools.

Heather Jacklin, a senior lecturer in the University of Cape Town’s School of Education, said the main problem with the country’s education system was inequality, which was not properly addressed after apartheid ended. “We just stepped down to a post-94 future where inequalities are not challenged by our labour market or in schooling,†she said. Jacklin said solving the problems with basic education could only be done by addressing social and economic inequality, and envisioning the kind of future we want to prepare learners for. For Jacklin, this is “a future in jobs but also a future as participants in civil society where they are able to engage, and a future where their chances are not stratified by the inequalities of the schooling system and inequalities of the labour market.â€

Sarita Ramsaroop, a lecturer from the University of Johannesburg’s Childhood Development Centre, said another way to future-proof school kids is to place greater emphasis on reading and writing in the foundation phase. Ramsaroop said that if children don’t have these skills, other types of knowledge, for example technology skills, would be unattainable. She said we also need to improve teaching skills, and develop better teachers’ networks – or “communities of practice†– so teachers could share their knowledge and improve their teaching to help find more engaging ways of teaching. “We can take from developed countries and apply the ways in which teachers are being trained to make an improvement in 21st century skills,†she said.

Brahm Fleisch, an education policy lecturer at the Wits University School of Education agreed that our education system should place greater emphasis on the early years of school in order to set children from all backgrounds up for success. Fleisch said many of the problems in our education system stem from the first three years of schooling. “We know that working-class kids, kids in rural areas, kids in township schools are not learning to read fluently by the end of grade three, which is required by the curriculum,†he said. This then negatively impacts how pupils make use of resources provided in secondary schools, he said.

The experts agree that that government must invest more in school infrastructure and teacher training. Fleisch said under-qualified and under-trained teachers were another key challenge. “The teachers haven’t necessarily gotten the right tools, resources and training and they don’t have right ongoing support,†he said. According to the national education department, approximately 5 139 teachers, most of whom are in rural KwaZulu Natal, are either unqualified or underqualified. “The district offices of provinces need to drive the processes, reprioritise their budget to make sure that their budget is being spent to ensure that learners are actually achieving the outcome,†said Fleisch.

Many companies are already feeling the effects of South Africa’s failing education system. In a 2013 survey, 80% of 200 companies polled said they were experiencing a skills crisis. The unemployment rate was 27.7% in the third quarter of 2017, and doesn’t seem to be improving.

Additional reporting by Ethel Nshakira