There’s a hole in the border fence that you can crouch and crawl through. Another that is tall enough for a grown man to walk through. The fence is a metal mesh and my first thought is: “Hell, these wouldn’t be hard to fix.†I tell this to the astute man driving me around, Jacob Matakanye – he’s the head paralegal and activist at the advice office in Musina (a town 10km from South Africa’s border with Zimbabwe). He says: “There is no point. The next day the holes appear againâ€.

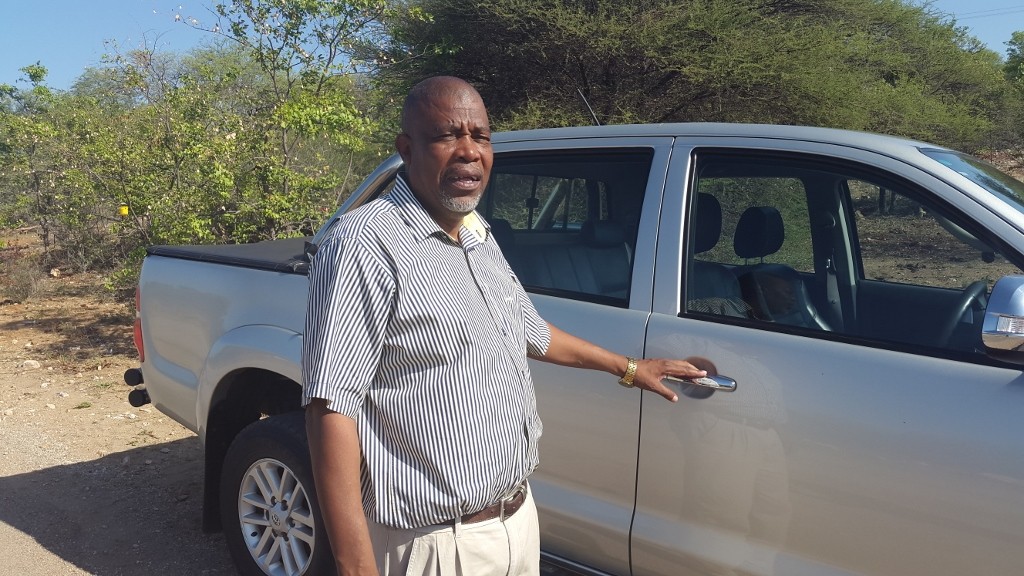

There are established camps of South African army officials opposite these fence holes: men and women in berets with guns policing the border. We even get stopped by a soldier and Jacob is questioned in Sotho. I ask him, after we’ve been allowed to drive on, if the soldier thought we were smuggling in Zimbabweans. He says: “No, cigarettes.†The soldier thought we were using Jacob’s twin-cab to smuggle in smokes from Zimbabwe. My second thought is: “We should just tear down the fence, sell the metal for scrap and deploy these poor, bored army troops elsewhere. Africa is one country, isn’t that right?†I tell Jacob this and he shrugs politely. He has also heard this before. Basically, my grip on our border situation lacks originality. I take dozens of photos of the fence and the holes as if I’m at a tourist attraction like Victoria Falls and then we drive back into town.

Jacob and his team at the community advice office in Musina have an intimate understanding of the concerns here, like the rights of foreign nationals. They make me realise why a journalist like me swooping in and producing these stories is not ideal. The community advice team, with their constant assistance of foreign nationals in South Africa, are going to add value to The Citizen Justice Network. CJN is a new innovation I started as an off-shoot of Wits Justice Project and The Wits Radio Academy. We train community paralegals to be radio journalists. We empower them with the journalism skills and technology necessary and carefully guide them so they can produce and broadcast their radio stories on their local community radio stations.

So far 10 community paralegals have been recruited by CJN across five advice offices. We are in Orange Farm (in Gauteng), Hennenman (in The Free State), Kwaggafontein (in Mpumalanga), Lebowakgomo (in Limpopo) and Musina. In each territory we have partnered with a community radio station that sees the value of these types of stories.

Our community paralegals are people like Jacob: established, trusted activists and fighters for social change in their communities.

Musina has plenty of wall-painted adverts for places offering deals for cheap calls home. The surrounding farms offer opportunities for work. Some Zimbabweans even commute over the border every day so they can stay at home and still earn South African currency. In 2009, Musina saw 1,000 foreign nationals enter the town every day, but that number has since dropped drastically.

Crystal Baloyi, a member of Jacob’s team and our CJN junior journalist, visits the detention centres daily and checks if any foreign nationals need medical attention. They make sure men or women haven’t been detained for immigration reasons for longer than 48 hours (they can be held for longer if there is a plan to deport them).

CJN’s final stage is community development. Our strategy of holding government accountable is to be collaborative. We see our goals as raising awareness, exposing dishonesty and providing a solution to government. This could take the form of an efficient information workshop: a day where government representatives provide community members with free legal advice around a particular concern that arose from several of our stories nationwide.

Local radio stations are incredibly popular, but local reporting is scarce. Most community radio stations do not have reporters or journalists. Members of radio stations often copy and translate news from national news sites for their bulletins. CJN is introducing the power of original radio documentary and narrative storytelling to community radio in South Africa.

Crystal says: “We are producing radio stories and these will be broadcast over the border and into Zimbabwe as well.†This is true: Musina FM (our partner radio station) has a reach into the surrounding area and into the adjacent country. “In this case we should be sure to produce stories for Zimbabweans who are thinking of coming to South Africa illegally. We want to warn them of the dangers,†she says. Zimbabweans making the trip can be mugged and raped by thugs who hide in the veld between the two countries. Crystal’s idea of using CJN to not simply produce stories for South Africans about immigration as a “problemâ€, but to include Zimbabweans in the conversation as a potential audience and addressing their difficulties is pretty wonderful.

Jacob and Crystal’s community advice office and Musina FM are partners of The Citizen justice Network. Read more on the project that’s training paralegals to be radio journalists at www.citizenjusticenetwork.org.

Paul McNally is the founding director of the Citizen Justice Network.Â