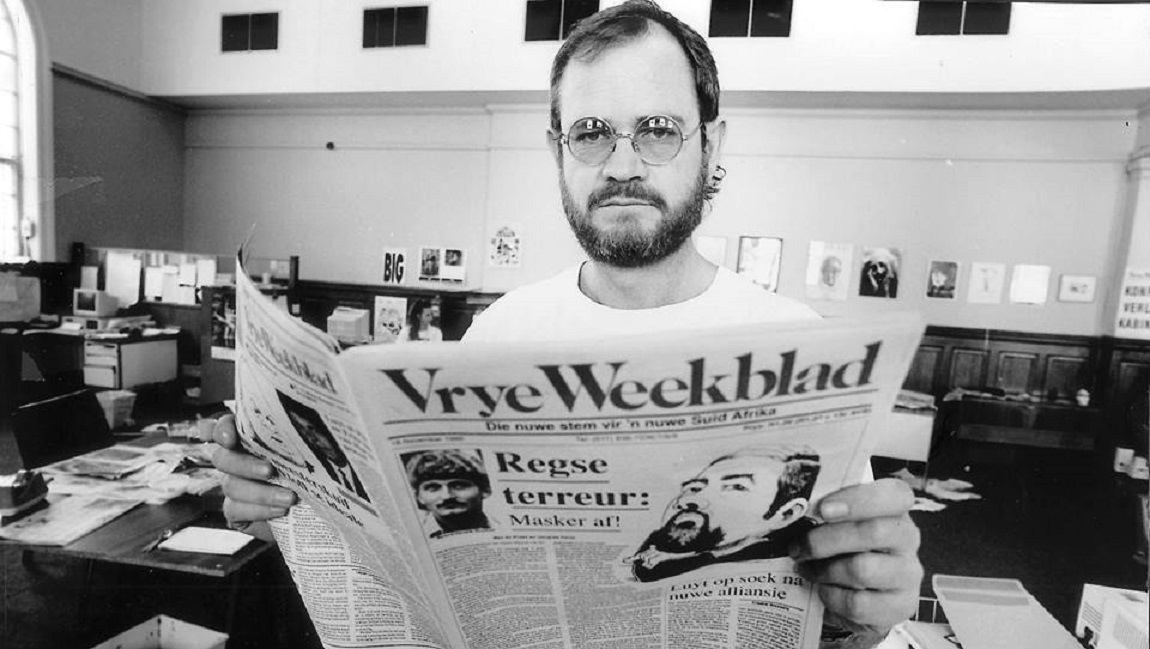

From the late 70s to the early 90s, South Africa saw some truly turbulent times. Journalist and social commentator Max Du Preez was at the forefront of exposing the apartheid government’s evil schemes from the death squads to the scientifically-formulated potions designed to kill activists. Du Preez ran these exposes in an independent Afrikaans newspaper called Vrye Weekblad. The Daily Vox chatted to Max Du Preez about his career as a reporter – and about everything in between from Vrye Weekblad and Stratcom to his perceptions of young people’s knowledge of the struggle.

You started your career working at Beeld and then moved on to other papers like the Financial Mail and the Sunday Times. What was it like working for newspapers supporting apartheid?

I went to Stellenbosch University and my mother tongue is Afrikaans, so it was a natural thing for me to work for an Afrikaans newspaper. It became clear to me pretty quickly that I could not serve an Afrikaans newspaper at the time – in the 70s – because of the slavish support of the National Party, of apartheid, and often of the wars in neighbouring states. It was a great relief in the early 80s to burn the bridges and say I cannot be a part of this. I went to work first for the Financial Mail and then for the Sunday Times because I had this in my head that the problem was with Afrikaans newspapers and if I moved to English language papers I would be able to serve my profession properly. When I got to the Financial Mail I realised the talk was different but the attitude was nominally the same – and so I started bumping heads with the editor at the Financial Mail. And that’s the way it went. Broadly speaking The Financial Mail and the Sunday Times at the time supported the status quo.

How did you start Vrye Weekblad?

In 1986 I got involved in an initiative to take Afrikaans-speaking opinion-formers to meet with the African National Congress in exile in Dakar, Senegal. We took 60 odd people over there and met with the ANC. We met with President Thomas Sankara in Burkina Faso and Jerry Rawlings in Ghana. For that I was fired from the Business Day where I worked at the time. The editor said I had shown my true colours as an ANC supporter. I was sitting at the Dakar meeting with Beyers Naude, Van Zyl Slabbert, and Breyten Breytenbach and we were talking about the negative reporting in South Africa about our initiative to break the deadlock and to start a culture of negotiation in South Africa. I said the media in South Africa is just disgusting and they challenged me and said, why don’t you start an anti-apartheid newspaper in the Afrikaans language that would give voice to those whose voices were banned and expose apartheid as a violent, evil ideology rather than some fancy separate development of nations. I took on that challenge and started the Vrye Weekblad in 1988 with no money and a small number of very committed people.

What were some of the challenges to setting it up?

Firstly, financial. No advertiser would touch it. We could not go to anyone who would compromise our project. It started by my selling my art collection, cashing in my pension and insurance policies. After that we got little bits of money here and there, we got money from the European Union for trading journalists, cheated a little bit and took money for the printer. But we had financial problems all the time.

The second problem was the state. It was a law at the time that you had to register every newspaper at the post office. They came to us and said they refused to support the newspaper because they suspected we were going to be supporting the enemy and why don’t you pay R50 000? They knew we didn’t have that kind of money. We went ahead and published without registering and so they took me to court on a criminal charge of publishing an unregistered newspaper. It became worse when the state realised exactly what we had set out to do: when we exposed the apartheid death squads, Vlakplaas, the civil cooperation bureau of the military, Stratcom, the third force in KwaZulu-Natal. I was taken to court 17 times in four years. I spent more time in court than in the newsroom. It was meant to financially ruin us because it wasn’t considered good strategy for the Afrikaner-led national government to jail an Afrikaans editors or close down the newspaper so they went about it with other ways. When it didn’t work they bombed our office in July of 1990; they tried to kill me twice. In the end we had to close down because of a court case.

What was the court case about?

When we exposed the death squad at Vlakplaas, we also exposed the goings on at the National Forensics Laboratory. The head of the laboratory was General Lothar Neethling and we had definitive evidence that he developed poison to kill activist and knock them out with what they called “knockout drops”. General Neethling, with the help of the state, sued us for defamation. That case lasted five years and was a massive drain on our finances. Eventually, in January 1994, we had to close our doors as a bankrupt company.

What were the reactions to the paper from the Afrikaans community?

The reaction was sometimes extreme and it was very negative. I was completely alienated from my own family. What we did was considered a betrayal of Afrikanerdom.

What do you think the importance of the Vrye Weekblad was?

The Vrye Weekblad was a small newspaper, its circulation was 25 000. It served as an important thing for two reason. For one, it put things like Vlakplaas on the record so people couldn’t turn back and say they could not know. We published it week after week for six years. The other was to set an agenda for the media and change what newsrooms were concerned about. We had sister newspapers: The Weekly Mail, New Nation, and South were our sister newspapers and we operated together as the so-called alternative media. One last thing – and I found this out afterwards – is that it was an inspiration for white and coloured Afrikaans-speaking people who were deeply troubled by the injustice of apartheid. It said to them: you are right, you are not alone and be strong. That sense of solidarity with the white left was important.

Let’s speak about Stratcom – from your perspective as someone who lived through it.

Stratcom is short for Strategic Communications and was the propaganda arm of the operation by the security police of the 1980s. PW Botha declared there was a “Total Onslaught on the civilisation in South Africa”. He said we needed a Total Strategy to counter the Total Onslaught. This meant there had to be a state security council, and not Parliament, who would run the country and it meant these operatives could break the law. They lived outside the law and that’s how death squads, torture, and assassinations happened.

They blew up Cosatu House and blamed the ANC. The head of the Coloured Parliament in the tricameral Parliament went to swim on a white beach as a sign of defiance, we had evidence that the state sent a security policeman to throw a hand grenade at his front door. The media reported that it was an attack by Umkhonto we Sizwe. That’s the kind of false flag operations they had.

So Stratcom planted journalists?

There were two or three categories of journalists. There were security policemen who paraded as journalists. There were a few journalists on the payroll approached by the security state who planted stories and got information from them. Then there were journalists in favour of the apartheid regime and willingly participated in propaganda campaigns.

Was it difficult to know which journalists were working for the state?

Sometimes we had our doubts but we couldn’t prove anything so we’d just be careful. Sometimes it was clearer. By the late 80s, early 90s, most of us had a suspicion of who these were but if you don’t have evidence it’s tough to confront someone and get them fired.

What do you perceive of young people’s knowledge of what had taken place in the 80s and 90s?

What I saw after the passing of Winnie Madikizela-Mandela was absolutely shocking. The level of ignorance about our past from young people including Julius Malema and Floyd Shivambu. The way they rubbished the United Democratic Front (UDF), saying the UDF were reactionaries not realising what the UDF was an organisation of more than 400 community organisations. It was an absolutely magnificent mass movement and it’s my contention that the UDF did more to force the apartheid regime to the negotiating table than the MK or ANC in exile. They made the country ungovernable and held mass rallies in turbulent times. For young people, if you only know the glorified history of the ANC is Lusaka then that’s a big gap. The demonisation of Desmond Tutu falls into the the same category. Desmond Tutu was a patron of the UDF, an inspiration to young people to take up the struggle, take risks, and fight apartheid. Now he is regarded as some kind of a sellout – and that is absolutely shocking.

Featured image via Facebook