Sitting in the lounge of a relative’s home in Klerksdorp, a small town in the North West, I listened as another visitor regaled us with her plans for retirement. The other women in the room, many of them older than her, expressed some concern. Wasn’t she too young to consider retirement? Wouldn’t she be bored? She listened to these questions patiently, and then settled back in her seat.

“You see,†she said to group of women seated in the large room, “Our shop is in a black area.â€

I looked at her, appalled. It’s 2014, we still have black areas? But it was about to get worse.

“I just can’t handle these black people anymore, and the comments they keep making about us Indians. You know, they hate us?”

Someone chirps up, before I’ve overcome my shock.

“Where is your shop?â€

“It’s in Natalspruit (outside of Johannesburg).â€

As she continued, my sister nudged me, my mother looked at me quizzically, I dug my nails into the palm of my hand, in an attempt to restrain myself.

Hers is the type of discourse that does not need to be peppered with derogatory terms to betray its racist bias. Â The way she spoke about her interactions with black people in and around her store in Natalspruit showed very clearly that she believed there to be an inherent inequality between black people and her. It is, to her, an Indian South African, an inequality that allows her to profit from the situations of black people in Natalspruit, people who she sees as lazy, envious, and entirely reliant on her taxes, while entitling her to a position that further entrenches her own privilege.

In her diatribe, she revealed the extent to which she sees an us and them. It revealed the extent to which she perceives herself as apart, superior to black people, as others.

And make no mistake, her words, casually delivered as they were, enunciate a violence, that is so deep seated, that it is perfectly acceptable to be spoken about in a lounge in Klerksdorp, while a group of women nod their heads and murmur in apparent agreement – while others, like me, restrain themselves from calling her out, lest it breach the carefully constructed code of politeness in place.

And while I never did do anything but appear aghast by her grand soliloquy, I was also left feeling disoriented and bruised, as though I’d just knocked my head.

It’s not that I’m impervious to the fact that these attitudes exist, I know too well that they do, but facing such an attitude with its volume turned up this high, was jarring.

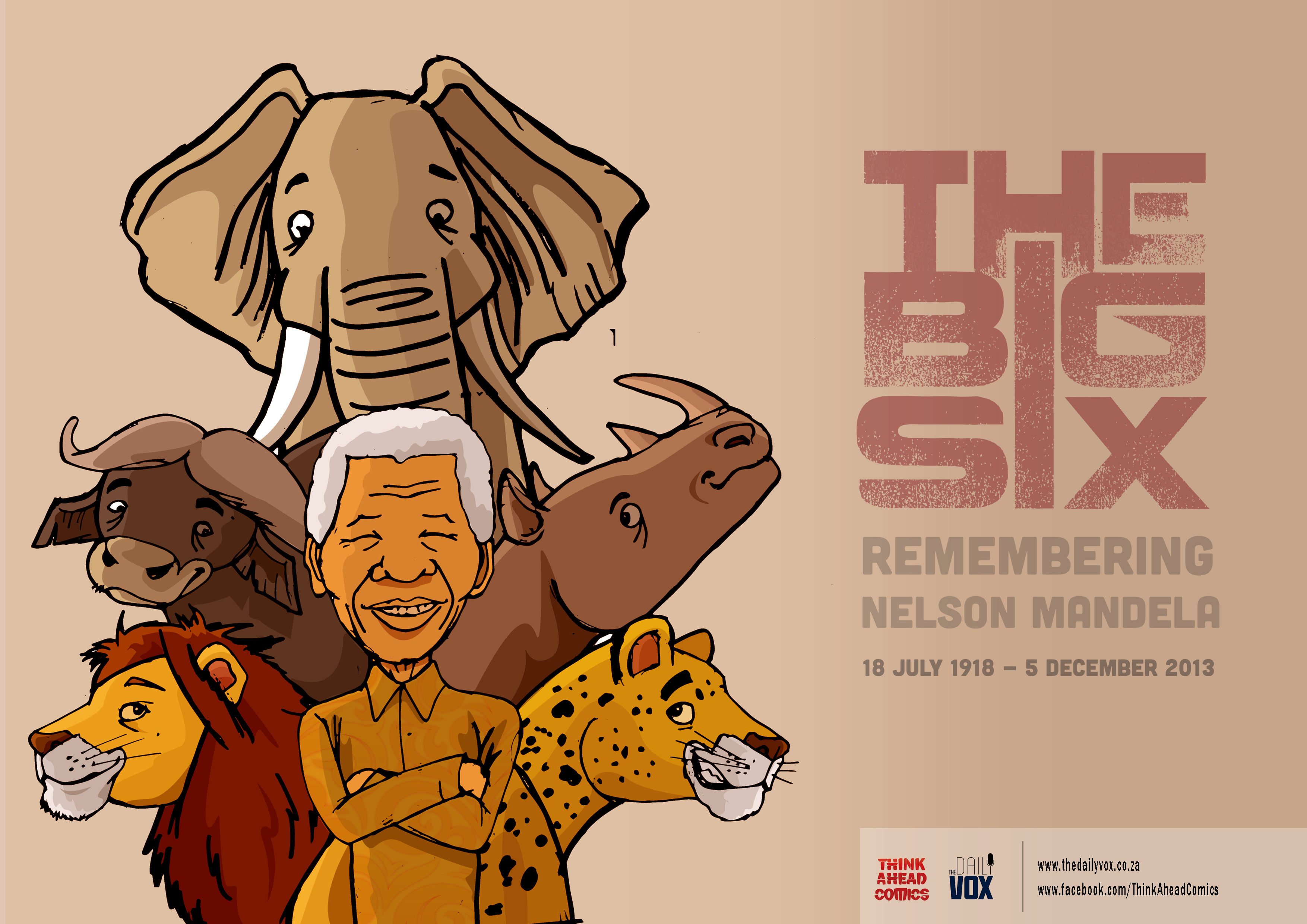

On Friday, in suitably sombre tones a plethora of news reports will remind us that it is one year since the death of Nelson Mandela. To the haters, the naysayers, the disbelievers, we showed ‘em that we wouldn’t go to war just ‘cause Madiba died.

But then, the problem is that we have come to see reconciliation in South Africa in the physical being of Nelson Mandela.

And yet, just because we haven’t picked up arms in a race war in the year Madiba has been laid to rest, does not mean that racial tensions do not exist. They do. And they are festering. But they are not a new development.

This week, a special edition of the Reconciliation Barometer showed that, “The period between 2010 and 2013 witnessed the steepest decline in citizens’ desire for a united South Africa”.

Speaking to The Daily Vox’s Ra’eesa Pather in Cape Town about the report, 29-year-old Siyasanga Zonke said, “ A lot of people aren’t even aware that they’re being racist because it suits their norm. We’re still stuck in the past, and 20 years into this so-called democracy, our job is to find ways to change the perception of black people.â€

Recognising that these problems exist however remains the easy part.

We know that these are the systemic challenges to our progress as a people. But what do we do about it? How do we get the Aunty with the shop in Natalspruit to look beyond herself, to recognise that supporting charities in the area is small change towards achieving real equality? How do we get her to even understand that her positions are entirely untenable?

And perhaps it is at times like these when we are looking for answers, searching for direction that we miss Madiba, and indeed others like him.

Far beyond the comforting narrative of South Africa’s miracle transition, Mandela is ultimately seen as a reconciler of a society that is fundamentally unequal, and entirely unreconciled.

Friday also marks 90 years to the day, the great Robert Sobukwe was born. And perhaps this too is an apt moment to reflect on Sobukwe, and his push for an Africanist agenda, especially when the ANC has failed to improve the quality of life of the majority of black people in South Africa.

And it would do us well to remember as well that Madiba was just a man, a mortal.

In his mortality we must also take strength. Just as he was a man who rose against oppression, and then forgave his oppressors, inspiring the idea of harmony and reconciliation, so too, we must find, within ourselves, the energy to confront the realities among which we live. Until we confront the structural imbalances of this country, imbalances from which many of us still draw our comfort, reconciliation will remain an idea, a dream deferred.

“It’s a mindset – people’s minds are still entrapped and imprisoned by the whole apartheid regime. The greats fought for us and I don’t think they fought for us to still be stuck in that time,†Zonke says.