The University of London’s School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) is the world’s leading institution for the study of Africa, Asia and the Middle East. The School was established in 1916 and tasked with development of colonial officials and administrators in order to strengthen Britain’s colonial interests across the world. In the post-colonial era, SOAS continued its focus on the former colonies and Britain’s past and present zones of geopolitical, economic, security and other interests.

SOAS has also become home to a powerful decolonisation movement and, in April 2017, Savo Heleta interviewed two members of the SOAS Students’ Union about their work. Neelam Chhara and Ali Habib were in South Africa to visit a number of university campuses and to engage with South African student activists.

Why are you campaigning to decolonise SOAS?

SOAS is currently celebrating 100 years of existence. Instead of celebrating its history, we should be challenging it – especially the institution’s contribution to colonial exploitation and oppression. The main aim of the Decolonising SOAS campaign has been to pressure the institution to acknowledge its colonial past and its contribution in the exploitation of so many countries. It also needs to widely and critically engage on its difficult legacy and to fundamentally change as we go forward.

SOAS has a high proportion of black and brown minority students. Its teaching and research focuses on Asia, Africa and the Middle East. The education in the UK, up to the university level, provides students with Eurocentric views and opinions that largely celebrate the empire and its accomplishments.

Those who feel disenfranchised by mainstream education and want to engage in critical education that goes beyond the description of colonialism as a force of “mostly good” look at SOAS as a space that is, in the eyes of many, an institution that critically interrogates the history of British colonialism. However, once they get there, they realise that the curriculum at SOAS – while more progressive than anywhere else in the UK – is still Eurocentric.

We are learning about Asia, Africa and the Middle East mainly from the Eurocentric and Western perspectives. We read white writers, philosophers and thinkers and their works about the “Other” in the former colonies. The thinkers and writers from the global South are ignored. This is why we have begun questioning what we are learning at SOAS. Most importantly, we are not calling for the removal of white philosophers and thinkers from the curriculum but for a greater representation of the thinkers and writers from other parts of the world – and particularly Africa, the Middle East and Asia.

What is the aim of the Decolonising Our Minds society?

We started the Decolonising Our Minds society at SOAS in 2014. Our focus was on organising events and creating spaces where students, academics and anyone else could engage on the issues related to the kinds of knowledge that are produced and promoted at universities in the UK. We also wanted to highlight the knowledges and thinkers that continue to be silenced and neglected.

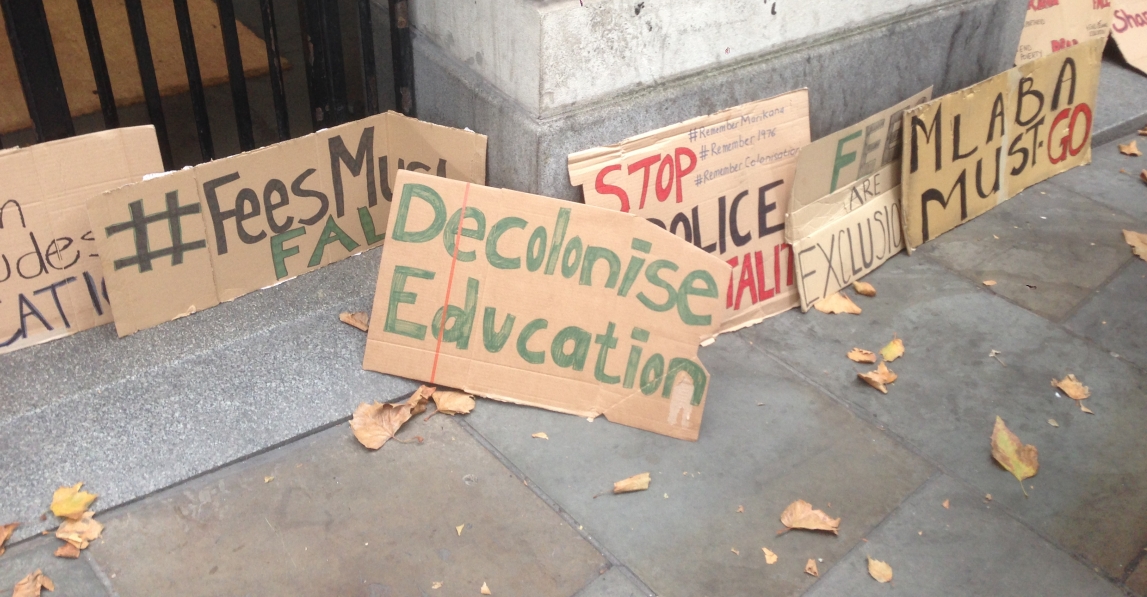

The #RhodesMustFall and #FeesMustFall movements that started in South Africa in 2015 had a big influence on our thinking and focus. Until then we hadn’t cared much about trying to transform our university. We didn’t think we would get anywhere trying to challenge the entrenched Eurocentric hegemony. Instead, our focus was on decolonising our own minds to think beyond the Eurocentrism within the curriculum and university. The developments in South Africa inspired us to change our focus and start putting pressure on our own institution to change.

The Decolonising SOAS campaign has attracted a lot of attention from the British media and media in some other countries. Most of it was negative, portraying us as “crackpot” student activists who want to get rid of white philosophers and writers. While most of the media coverage was negative, it was still beneficial to us and our cause. It highlighted our work and got people thinking and asking questions that were not being asked before.

You had opportunities to engage with students from different institutions in South Africa. What is your impression of the country’s student activism?

A lot has been achieved in a short period of time in South Africa. Students were able to start a public dialogue about government’s lack of support for higher education, the Eurocentric curriculum, lack of transformation and exploitation of outsourced workers by universities. Student activism also managed to remove the statue of Cecil Rhodes at the University of Cape Town. None of this would happen without their activism.

We have had constructive and inspirational engagement with students at a number of universities. The student activists we met in South Africa are definitely on a higher intellectual level when it comes to their thinking and articulation of demands than any students we have met anywhere else.

We just had a powerful meeting with the co-founders of @RhodesMustFall #decolonisesoas pic.twitter.com/7UKGl8Hqzv

— Ali Habib (@Habibiline) April 20, 2017

At the same time, we realised that there are deep divisions among South Africa’s student movements. Many of these divisions are based on political, ideological and class differences. There are also issues of intersectionality and patriarchy. These divisions are negatively affecting the movement’s ability to operate and engage and are playing into the hands of those who want to maintain the current oppressive system.

Despite all the challenges, we are witnessing social awakening among young people – from South Africa to the UK, the United States and many other countries. They don’t accept the status quo and are not afraid to campaign for change. This won’t stop just because the authorities and university leaders want it to stop. It will only stop if there is real, fundamental change of the status quo. But change won’t happen overnight. We need to accept this, plan accordingly and keep going.

Featured image by Philip Owira