A commute by taxi may be cramped but is also filled with colour and character. Daily Vox Durban correspondent SHIMEI GANESH took a trip from Howard College to Warwick Junction. This is what he found.

In order to successfully carry out an expedition from the local taxi rank to Howard College Campus and back home, at least three things are necessary: a minimum of thirty-seven South African rands in my wallet; a mind that is prepared for any hurdles that a routine commute in Durban may place in front of me; and a vague knowledge of which hand-signs I should employ to ensure that I’m picked up by the correct taxi. The third involves knowing which of my digits to hold out, and in what shape. A combination of these two factors determines my destination.

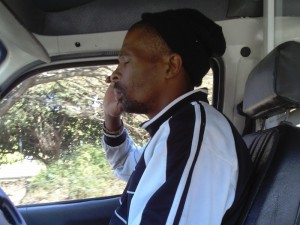

On this particular occasion, an upward-pointing index finger signals a rusting, white Hiace to stop only a few feet away from the pavement I am standing on. I’m greeted by Nipho, a middle-aged black man wearing an Orlando Pirates beanie, a pair of worn-in Dakotas that have certainly seen him through many years of serving in the taxi industry, and a bag under each of his eyes that tell a story of exhaustion. Nipho tells me that a typical work-day commences at roughly 4am. He travels between the Durban and Pinetown CBDs at least seven or eight times a day, and returns to his home at roughly 8pm every night.

He’s a little uncomfortable with being bombarded with so many questions, so I remind him that I’m simply trying to learn a little more about the life of a taxi driver. While thinking about a tactful answer to my question about whether he is married, Nipho rolls my R10 note into the shape of a cigarette and fits it snugly between the horizontal pieces of what was once an air conditioning vent, adding to a collection of notes that are as meticulously rolled up. His hands carry no fewer bruises than his old, brick-like Nokia.

Our short meeting itself is brought to a dramatic end when our entrance into the vicinity of Warwick Junction – popular for being one of Durban’s most dangerous locations – is met with shrill shrieks. Our taxi is stopped in the middle of the road by a mob of somewhat angry men. Doing my research on the public transport system in Durban, what are the chances of finding myself at the very epicentre of a taxi strike? Members of the angry mob, who had started off by shaking their index fingers at Nipho as a warning, proceed to reach through the window on my left and past my face to reprimand him further. His surprisingly casual reaction implied that he knew they had no intention of harming him, but rather of taking his taxi off the road in order to ensure their strike’s effectiveness.

Surprised as I am to find them guiding me out of the vehicle without the use of brute force, I struggle to process the sight of an audibly disconcerted mob helping an elderly woman carry her Checkers packets to the side of the road. A young black man wearing dreadlocks and an Elton John-like gap between his two front teeth tells me that “they are stopping all the taxis with people in them,†but isn’t able to provide any further insight on the matter.

Walking roughly two kilometres from Warwick Junction to the landmark Workshop, I am met by young men washing and cleaning taxis, streams of people queued alongside taxi ranks that I pass through, and a big-bellied, dark-skinned coloured man raving to his friends that “they tried to moer [him] off the road!â€

He introduces himself as Vusi, a father of three who resides in township. Describing himself as “self-employedâ€, Vusi explains to me that township refers to KwaMashu, where he runs a “mini-shopâ€.  From the agreeable smile that lights up his face when I ask about the success of his business, I gather that Vusi’s mini-shop has been good to him. “I’m not worried about the taxis because we have our own car,†he explains to me while watching over three curious little faces at his side. “Today I take the taxi so I can show my childrens around eThekwini.†He politely declines my request to take a picture of him and his family and sends me on my way with a friendly “hamba kahleâ€.

It is protocol to wait for the Howard taxi to fill up to – and in some cases, above – carrying capacity before the vehicle departs from the Durban taxi rank. When jumping on any taxi that travels between the Workshop and Howard College, the trick is to avoid sitting next to the driver. It is the generally accepted task of the passenger occupying this seat to help out with the collection of taxi fares. Such a procedure entails understanding what is meant by three threes and four fours, ensuring that the correct amount of change is sent back to the rest of the passengers, and most importantly, handing the correct amount of money to the driver.

Sheelavathi, an elderly Indian woman who disembarks with me, identifies herself as a Hare Krishna devotee. She is dressed in a pink sari, wears a red dot between her eyebrows and carries the pleasant fragrance of an incense stick. She tells me that she is from Chatsworth, and that “her initiated name has transcendental meaningâ€. When I ask whether she travels via taxi on a regular basis, Sheelavathi’s reaction is an immediate “No, no, no!”

“I was stranded yesterday and today, but someone usually drops me off,†she tells me. I get the impression that public transport is a last resort for people as fortunate as her. This is a departure from the realities of many commuters who have no other choice. “You must come to our temple and we will give you nice input for your article,†she says before making her way to a seminar that she is helping out with.

“Personally, I hate public transport,†declares Nizam, a young coloured gentleman who works at Adams Booksellers & Stationers. He travels via taxi on a daily basis, but admits that if he could get in a car and travel to work, he certainly would. He jokingly adds: “Heck, if I could get in a car to go to the toilet, I would.†When I ask for his opinion on the advantages of travelling via taxi, Nizam tells me that it provides a good forum for meeting people and making new friends. “Two girlfriends through taxis,†he proudly shares while holding up two of his fingers. “It’s not that it’s a bad thing, it’s just some of the kombis as well. They still got these doors that fall off, holes underneath your feet like, okay – I’m seeing the road now. That’s not right. Travelling by taxi has its ups and downs. I just wish they would take al die krap kombis off the road, you know?â€

Owing to the taxi strike, I’m forced to travel home by bus – a mode of transport that I am unfamiliar with. I watch an elderly, white man take a generous swig from the nip of Mellow-Wood brandy that he keeps in the inside pocket of his worn-in anorak It is roughly 4pm, and the faces of fellow passengers tell the story of fatigue, but not discontent, after a long day of work.

Nipho still has at least another four hours to go before making his way home.