This week MPHUTLANE WA BOFELO speaks with activist, trade unionist and writer Allan Kolski Horwitz of Botsotso Publishing and Botsotso Jesters fame.

MwB: Who is Allan Kolski Horwitz and what is his philosophy of life?

AKH: “For some too anarchistic, for some too structured; for some too extreme, for some too soft; for some too arrogant, for some too self-effacing”

There is a cliche that still holds water: afloat in human history, a tiny vessel on an ocean of timelines, an individual life, despite its intrinsic uniqueness, can seem very insignificant. When I was twenty-one, in the middle of an acid trip, I consolidated an earlier epiphany in relation to the utter relativity of our experience of the interweaving dimensions of time and space. I was looking at the brown and purple outline of Signal Hill in Cape Town, and knowing that I was one day going to die seemed not only inevitable but necessary as the giant mound of earth and rock that filled my vision seemed to lift up and crumble and fly away as the process of dissolution unfolded. The old must give way to the new. And this sense of the innate dynamism of, what we call Life is at the core of my beliefs. As such, holding on to what gives us comfort and pleasure, what stabilizes us, is important, but above all we need to embrace challenge and risk so as to live authentically and fulfill our aspirations.

No one creates him/herself alone. The family constellation, the culture, the language and above all, the class, into which we are born, shapes who we become. My acceptance of historical materialism as a key tool for understanding human societies and the individuals they produce was a seminal point in my intellectual and psychological evolution. When Freudian and Darwinian concepts were added to this, as well as those elaborated by Fanon, Einstein and Gregor Mendel, the architecture was almost complete. But not quite. The inner voices of Zen Buddhist thinkers and those of sages of other cultures (from ancient times to the present) evoked and challenged my own spirit.

And there were the presences of innumerable artists – writers, painters, playwrights and film-makers – whose works inspired within me a consciousness that seeks to unite creative, cooperative energy, both in maintaining relations with other people and in making art. As such, I have always felt that being a human rights activist and being an artist (in different disciplines and genres) are two sides of the same coin, and that both are intrinsic to the most satisfying “way to live”: namely, being open and sensitive to others, and being able to make “magic” with words and images and sounds.

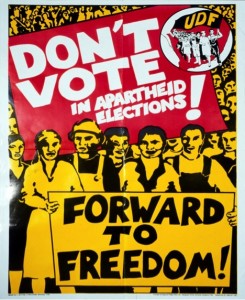

As the child of a Jewish Holocaust survivor, I know the pain my mother carried; a pain and depression that ebbed and flowed across her life, and as she aged, grew more acute. I carry that pain in my marrow. I also felt a deep love for her, not just empathy. This showed that despite the odds, living could be a fulfilling experience. And because she was also a woman whose natural vitality could not easily be suppressed, through her I felt the possibilities of creativity, the transcendent power of a spiritual life. It goes without saying that growing up in Apartheid South Africa was a major factor in shaping me. The brutality and stupidity of this system pushed me towards radicalism. Evil can only be restrained if full consciousness is reached as to our choices: whether or not to do unto others as we would have them do unto ourselves – or to live trapped in manipulative, exploitative relations.

I hope this sensibility is at the heart of my poetry: the psychological encompassing the sub-conscious, the archetypal, the hidden worlds within us; the political covering the overt social and economic spheres with all their varying relations. Power takes inward and outward expression. The harnessing of energy – to do things, to make things, but also to break the outmoded, the irrelevant – is a critical element in sustaining the life force. In relation to my current understanding of where we are located in South Africa, I must say that tragically, 20 years after the political victory of anti-apartheid forces, we have seen a withering away of commitment to egalitarian and democratic practice within these formations. We have also seen splintering of those who wished to resist the bitter analysis that Fanon delivered on the Liberation Movement elites.

South Africa’s new elite has travelled the same hypocritical road that most of Africa’s movements have travelled. Yet we are a resilient society, so despite these betrayals we will hopefully, in time, counter their destructive influence. This, of course, will necessitate confronting Big Business and other deeply entrenched interests. Only a self-conscious and “purified” working class together with the more progressive in other classes will manage to make the changes that are needed. What can my contribution be? Where possible to support genuine initiatives to build a new generation of mass democratic organization as well as to create art that continues to address the realities of our world as well as expressing the human imagination. All is not lost, but the responsibility to counter crass materialism, cynicism and escapism is clearly a never-ending struggle.

MwB: Can you share with us your experiences of working as an organiser and educator in the trade union movement?

But let me return to that revolutionary period, for despite the terrible bloodshed and suffering, it would be true to say that in terms of creativity and solidarity it was the most fertile period in South Africa’s colonial and post-colonial history. For millions, the power to control one’s life was not just an objective but an actuality and I was swept into this revolutionary tide with an enormous sense of belonging and purposefulness. Finally I was no longer on the social and political margins but an active participant in a great movement – the political and the personal were perfectly harmonised. In particular, as a middle-class, white man who does not speak any of the vernacular languages, it was a very liberating and educational experience. I would sit for hours in meetings listening to workers debate and discuss in their home languages. Slowly but surely I picked up words and phrases and began to decipher the body language that accompanies torrents of expression. Having lived overseas for so long had helped me to overcome the cruder forms of racism but being immersed in the trade union movement carried me beyond the last vestiges of the apartheid barriers.

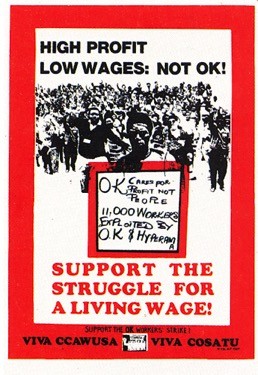

Once in the trade union, without any training or knowledge of labour law, I entered the maelstrom of dismissals, grievances, recognition struggles and wage bargaining. Employers regarded hospitality workers as little more than domestic servants. Wages and conditions of work were accordingly extremely low, many workers lived in unsanitary, badly built, over-crowded hostels or compounds, there was no skills training, no procedures to regulate employer-worker relations. However, in a period of just five years we – a group of four full-time organizers and several dozen shop stewards – organised over 14,000 workers into the Hotel and Restaurant Workers Union (HARWU) and created national alliances with a range of other unions.

We instituted fair procedures and took up campaigns for a living wage and other rights including centralised bargaining in the various provincial structures. This also extended to pension/provident funds and other benefit schemes. At another level it was a privilege to participate in the development of Cosatu into a giant of working class leadership. To be sure there was another darker side – being thrust into the very bruising and destructive CCAWUSA split between Charterist and independent socialist factions in 1989/1990 was a traumatic experience and gave me a taste of the no-holds-barred struggle among the different liberation movements – but the overall experience of participating in Cosatu CEC’s, commissions and congresses was massively enriching and rewarding. We worked long hours for very low wages but this was a small price to pay for being part of a historic movement.

In HARWU I had done everything – organizsng new members, coordinating wage negotiations, running shop steward training, being a trustee of pension funds, consulting with lawyers and liaising with international trade union organisations. In SACCAWU, the union that came into being to heal the CCAWUSA split, I became the national catering coordinator but after two years decided to leave as the organisational tensions and hostility to catering workers became too much to bear. The disintegration and corruption of SACCAWU over the past 20 years has proven my analysis correct. Political blindness , seen in the union’s support for the ANC/SACP , tolerance of dishonesty are a toxic combination that has left workers in the retail and catering sectors defenseless against neo-liberalism.

Organising is hard work, often tedious. Dealing with both workers and employers one needs to cultivate different skills. The environment in the 80’s was such that most workers were very open to unions, if sometimes afraid of their bosses. The bosses on the other hand were by and large hostile but were aware that the tide was turning and that black workers had rights that could not easily be denied. This did not mean that they welcomed the union with open arms but it did mean that, in most cases, we won recognition and were able to almost immediately secure tangible gains. This meant that the union established itself and could grow and develop its membership. Training shop stewards, giving them the confidence to manage most disciplinary and grievance issues was paramount and in terms of such education, COSATU affiliates did a fantastic job. Sadly over the past 20years this legacy of thorough empowerment of the shop floor leadership has largely died.

Today most unions have grossly inadequate education departments and many shop stewards are at sea when it comes to performing their basic responsibilities. The need to revive mass worker education has never been more important but tragically it does not appear that this is about to happen. A key element of worker organisation is political education. This covers the workings of the capitalist economy, the history of human evolution, the nature of class struggle and the integration of the spiritual and material in our lives. Given the degeneration of most struggles for socialism it is clear that only a deep and thorough program to develop a new co-operative, democratic consciousness will see the withering away of violence, ignorance and exploitation as human conditions. Sadly, the organisations that currently exist are not providing such a path for workers.

MwB: You are part of Botsotso Publishing, which among other things published the literary magazine; Botsotso and of Botsotso Jesters together with Ike Mboneni Muila and Sphiwe KA Ngwenya. Please give us some insights about these projects.

AHK: The best description of Botsotso is captured in its mission statement.

“Botsotso is a grouping of poets, writers and artists who wish to both create art as well as to generate the means for its public communication and appreciation. We speak particularly of art that is of and about the varied cultures and life experiences of people in South Africa – as expressed in all our many languages. Botsotso is committed to a proliferation of styles and a multiplicity of themes and characters. Multidisciplinary art forms and performances are similarly embraced. The transition from a closed, authoritarian society to a pluralistic and democratic one offers artists an opportunity to explore the truths of our inner and social lives with a freedom that has not existed before. Flowing from this, the consequences and lessons of Apartheid must still be examined while the challenges of the current period throw up their difficulties, their complexities. Botsotso works with inter-action: the different elements of the South African mosaic colliding, synthesizing – affected both by social forces and the individual’s uniqueness.”

Here is a glimpse into the writing and performance of the Botsotso Jesters:

POETIC SCRIPT

SIPHIWE: Pensioner standing in a queue

ragged animals in the zoo

yawning toothless lions

ALLAN: I am fire burning the shack

no jobs and drink lead the attack

hey, sweetie – get flat on your back!

IKE: Soul food binder stay free

silaphanje nge mum for men

eat your heart and lungs out

SIPHIWE: Listen to my voice at the shop door

listen as you walk to the sounds of war

umngena ndlini mama, umngena ndlini baba

ALLAN: Stink of scam in the State

bureaucrat shuffle while you wait

nepotists scoop the honey

IKE: Stripper lelohembe asidlali

nkhetheni ke wa ponto le sheleng

sendela ngeno kanna legetleng

SIPHIWE: Shebeen tables black with booze

girls caress beards of their fathers

mothers bump and grind with their sons

ALLAN: I’m the bull running this kraal

don’t pull my ring if you’re skraal

roll up – Sun City extra!

IKE: Hout kop petty crime is a taboo

shame on you daaso a ni hembi

guys ni hava nchumu jokes aside

SIPHIWE: Darkness shadow in the slums

pockets cold with a stainless knife

pass the bucks or I’ll take your life

ALLAN:

Total Onslaught amnesty

even Wit Wolf walks out free

forgive and forget history?

IKE: Ginger face butters no record to trace

ready stomach digests sound of my words

no bubblegum music in my verse

Ike I am skinny bowler wind skeleton touch

spoko mathambo by virtue of birth

I can read the scareness in your eyes

Allan mps travel two by two in four by four style

corporates build a serious bonus pile

in the ghetto kids become suicide projectiles

Siphiwe I have an urge like burning fire

let me release this flood of desire

on every woman I meet before I spit

Ike bully bull brand beef stalk in your face

prima facie redtape windhoek hushpuppy doll

check it rubber neck bell ringing moo more school in

Allan Affirmative Action with a touch of class

line up for directorships and down a full glass

while US aid covers your arse

Siphiwe I am a hawker in a jozi street

cops stole the fish on my dish

but haai! I have not lost my jester speech

Ike to my health supervisor ringas before suffer gate

mummy blue skatie pass the dice

deal with the root of poor health poverty

Allan I am the man with the golden tan

don’t pull at my skin or scratch

- cause underneath the gold is an umlungu whose met his match

Siphiwe I raise a Diepsloot fire because of rumor

from MaMgobhozi’s bitter sense of humor

poking the government’s brain tumor

Mphutlane wa Bofelo is a South African poet and essayist; cultural worker and social critic who is influenced and inspired by Black Consciousness, Sufism and radical humanism and socialist humanism. He holds regular conversations with the nation’s anarchists, rebels and dissidents.

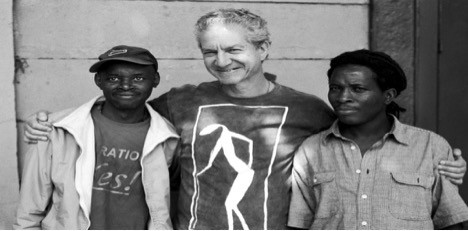

![Allan Horwitz [slider]](https://www.thedailyvox.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/Allan-Horwitz-slider.jpg)