President Jacob Zuma’s Presidential Commission into the introduction of free higher education in South Africa held its final sitting of 2016 on the 29th of November. The final arguments were heard from Thusanani Foundation, whose presentation rejected widely held views on free higher education including Sizwe Nxasana’s proposed Ikusasa Student Financial Aid Programme (ISFAP). This is an edited version of that presentation.

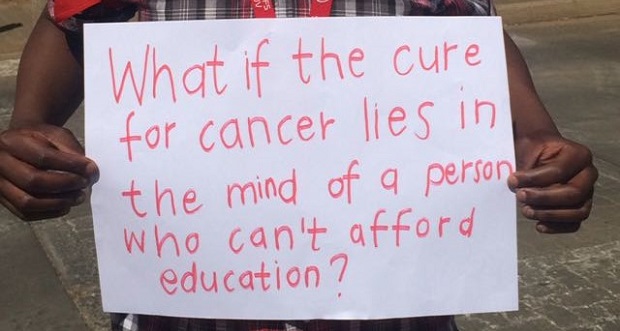

Despite a strong national policy commitment to making higher education accessible to poor and working class youth, a post-1994 neoliberal approach to education has underpinned the continued commodification of higher education as a private good increasingly inaccessible to millions of poor and working class youth. It is this approach to higher education, in a rapidly modernising economy, that has led to an unmitigated socio-economic genocide on the dreams and aspirations of millions of poor and working class youth, laying a solid foundation for the higher education funding crisis facing South Africa today.

Central to the South African higher education funding crisis is a university system that is grossly underfunded, small in size and increasingly sold like a commodity in the market place, with the financial burden increasingly transferred to individual students over the past two decades. Whilst the negative consequences of this higher education system have been felt across the social spectrum, they have particularly paralysed the educational and social mobility of youth from low income households and communities, permanently condemning millions into the NEET (Not in Employment, Education or Training) cycle of poverty, inequality and unemployment.

We put forward to the commission that, given her history and the current socio-economic reality of our country, a just and sustainable solution to the current higher education funding crisis is only attainable when higher education is declared and viewed through the lens of a public and cultural good whose equitable accessibility is a necessary pre-condition to South Africa’s future socio-political stability and national security.

Our universities increasingly occupy the role of a smokescreen that facilitates the undetected perpetuation of social inequality by enabling the normalisation of structures of socio-economic domination in patterns of educational attainment and society in general under the pretence of academic neutrality.

Out of every 100 students who enroll for grade 1, only 60 students reach grade 12. Of the 12 students with university exemption, nine of them come from adequately resourced privileged quintile five schools; the poor in quintile 1,2 and 3 schools scramble for the remaining three places. Nationally, of the 984, 000 students enrolled at 26 public universities, only 180, 000 (18.2%) are funded through a mixture of loans and grants from National Students Financial aid scheme (NSFAS). The rest are left to scramble for external bursaries and assistance from loan sharks preying on the poor. At an institutional level, of the 20, 000 financial aid applications received by Wits University only 3, 100 returning students and 400 new entrants were awarded financial aid packages. In other words, out of 6, 000 first time entrants enrolled at Wits University during the 2015 academic year, only 400 students received NSFAS financial aid packages.

Higher Education Ministry’s 0% and Nxasana’s proposed Ikusasa Student Financial Aid Programme

With the above picture in mind, we submit to the commission that the position adopted and presented by the Department of Higher Education and Training (DHET) and the Council on Higher Education (CHE) with regard to the 2017 university fees amount to a gross underestimation of the impact that the ever-rising cost of study has had on students coming from low-income households and communities over the past two decades. The narrative that “the poor are being taken care of at universitiesâ€, as advanced by the DHET and some university managers is not only misleading but also largely responsible for the resurgence of protest action across campuses. Evidence from national and institutional data point to the contrary of this narrative, particularly at elite institutions.

Government’s failure to maintain a moratorium on university fees until the anticipated inclusive funding model of this commission could be finalised, as well as contradictory messages from various government departments and university managers regarding the future of higher education funding in South Africa, not only primarily sparked and fuelled student protests but further threaten the legitimacy this very commission. Contrary to its expressed intentions, the “2017 0% increment for the poor†committed by the DHET has actually taken away from the poor by cross-subsidising the continued commodification of higher education by university managers in that government is still paying for the difference/shortfall between 2016 university fees and the permitted 8% increment resulting from University Councils’ discretion.

By handing the power to determine the cost of study back to university managers before the anticipated model of this fees commission could be finalised, the government has effectively undermined its political responsibility to deliver higher education as a public good, a cultural good and, most importantly, an apex priority of government. By failing to maintain the moratorium on university fees whilst this commission probes the current anatomy of university fees and comes up with an inclusive funding model, the DHET, contrary to its expressed intentions, has, in reality, endorsed and legitimised the continued commodification of higher education by university managers under the hoax of institutional autonomy.

Furthermore, it is our strong resolve that the posture and content of the “Nxasana ministerial task team†and its proposed ISFAP not only continues on the neo-liberal and meritocratic trajectory of the current higher education funding model that has brought us to the crisis we are in today, but is also reflective and littered with the interests of the private banking and legal sector masked under a proposed Public-Private-Partnership (PPP). At times, this posture appears contradictory to government’s efforts to widening participation in higher education.

For example, the task team not only suggest the replacing of the current NSFAS model with a privately managed “Ikusasa Student Financial Aid Programmeâ€, but further recommends the integration of private banks’ student loan products into the proposed “Ikusasa†funding model. Private banks’ student loans have a globally acknowledged exploitative reputation which is contrary to government’s policy on higher education policy. What is particularly concerning with ISFAP is that the contribution of big business towards the funding of low-income students is largely left voluntary. We further propose that ISFAP’s proposed BBB-EE skills levy, as a source of alternative funding for higher education, be further probed as it presents a possible window for big business to avoid the transformative ideals of the BBB-EE act in so far as the transformation of patterns of ownership and control of the economy are concerned. Our position is that students must outright reject ISFAP as nothing but a bad attempt at rebranding limitations of NSFAS under a worse privately run scheme.

We further submit to the commission that the current state of higher education funding model is inconsistent with section 29 (1)(b) of the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa which state that “everyone has the right to further education, which the state, through reasonable measures, must make progressively available and accessibleâ€. All evidence point to the fact that the state is currently in possession of reasonable means necessary to realise the immediate introduction of fee-free higher education and training for youth coming from low-income households, failure of which threatens the legitimacy of a hard-won democracy and our future stability.

The meaning and content of “free higher education and training”

All previous commissions and task teams on the feasibility of higher education and, sadly, the interim report of this very commission all define “poor and working class students†as “Students from poor households with an annual income below R122, 000 per annum based on current NSFAS rulesâ€. We submit to the commission that this definition of “poor and working class students†is exactly what is fundamentally flawed and problematic with the current as well as their newly proposed student funding models.

Firstly, the annual household income of R122, 000 as criteria for one to be declared “poor and working class†has remained unchanged for almost two decades despite the cost of study and that of living having more than doubled in the past decade alone.

We find the definition of “missing middle†by the Nxasana ministerial task team and the interim report of this very commission equally flawed and problematic. Given the socio-economic profile of South African households, students who have been defined as “missing middle†are in actual fact nowhere near “middle class†when measured by household income. In a country with a Gini coefficient of 0.7, it is grossly inaccurate to brand a daughter of parents with an individual income of R61, 000 per annum (or R5, 166 per month) as anything that resembles “middle class†and therefore not eligible to qualify for a fully subsidised full cost of study at higher education institutions. In determining one’s class position in an economy similar to ours, it is unjust to evaluate the value one’s household income in isolation from the cost of living (in this case, cost of studying).

Keeping in mind the recent history of rapidly escalating full cost of study, the socio-economic profile of South African households and the income inequalities in our country, guided by the principle of redistributive justice and in pursuit of collective social mobility and justice, Thusanani Foundation submit that the commission revise and adopt the definition of “woor and Working class students†to refer to students coming from households with an annual income of not more that R 300, 000. Having amended the definition of “poor and working class studentsâ€, Thusanani Foundation calls for the immediate introduction of free (i.e. fully subsidised full cost of study) higher education for all poor and working class students in the form of government grants. We submit that full cost of study includes tuition fees, accommodation, meals, transport, and all study material.

It is our estimation that the R300, 000 per annum cut-off will benefit well over 80% of South African households including: The unemployed (27%); 16 million social grant recipients (45% of households); employees earning below taxable income (70% of the labour force), civil servants such as: teachers, nurses, social workers, garbage collectors, artisans and other low income earners such as farm workers, domestic workers, mineworkers and security guards. Adopting this definition will mark a bold step in South Africa’s efforts to break with the socio-economic legacy of colonialism and apartheid that continue to polarise our country along class lines.

The estimated cost of introducing free higher education for poor and working class students

The Nxasana task Team and PricewaterhouseCoopers have estimated the cost of introducing grants and loans for “poor and working class students†and “missing middle†at around R50 billion. Having accounted for variations in cost between contact and distance students, historically disadvantaged universities and elite institutions, we have estimated the cost of introducing free higher education for students from households with an annual income below R300, 000 between a conservative R35 billion and R40 billion.

The current higher education funding model continues to play a major role in enabling affluent sections of society to transfer a host of social, cultural and economic advantages through generations whilst achieving the opposite amongst low income households and communities. Should the current higher education funding model not undergo bold and deliberate reform, it will not only halt efforts to advance the struggle for social justice in South Africa but will further exacerbate the spread socially unequal patterns of educational attainment across future generations. This commission is entrusted with a rare opportunity at this very moment in history to meaningfully correct the ills of our past whilst laying a solid foundation for a more just and humane future of our country.

Mukovhe Morris Masutha is the founder and executive chairman of the Thusanani Foundation.