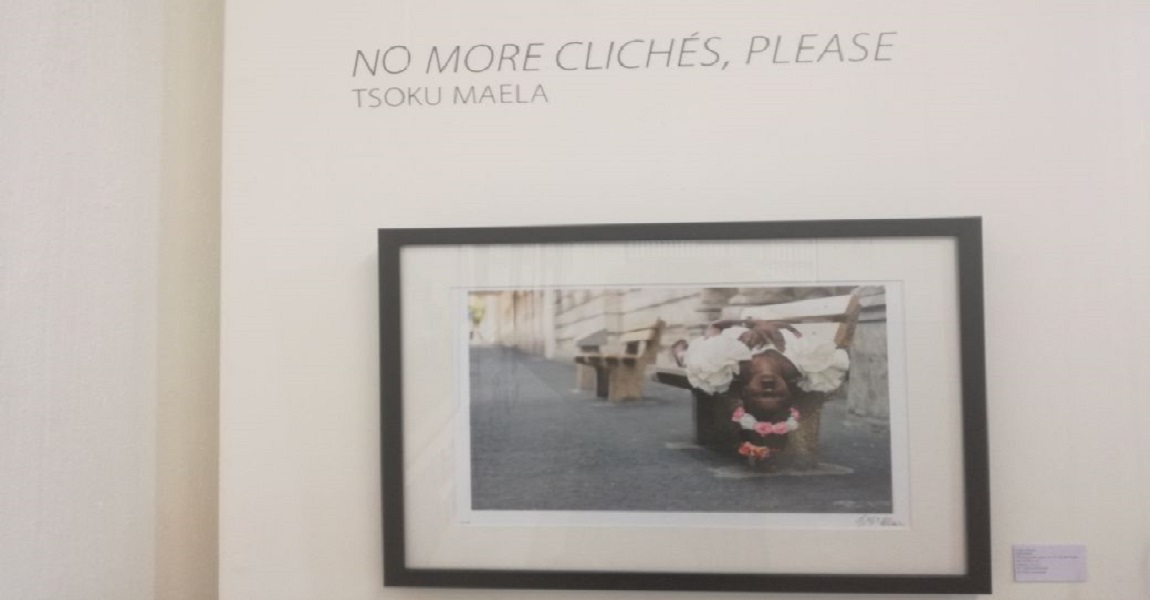

With No More Cliches, Please artist Tsoku Maela endeavours to capture the resistance of brown women and to address the clichés associated with resistance and the brown female figure. Maela’s body of work melds imagery, poetry, and protest in a carefully curated array of photographs, poems, emails, tweets, and recordings of conversation and song. The exhibition is a conversation about the cliché of resistance often encapsulated in the contours and shapes the brown female figure. The Daily Vox spoke to Maela and visited the exhibition.

The body of work is a new exhibition in itself. It’s my first solo in Johannesburg. I decided to go with a different collection of work looking at the female form, more specifically the brown femme form.

I’ve been shooting these images since about 2016. It’s like a curation of all the awesome work of brown femmes who have given me consent to use images I’ve taken of them. It’s a study of the brown femme form.

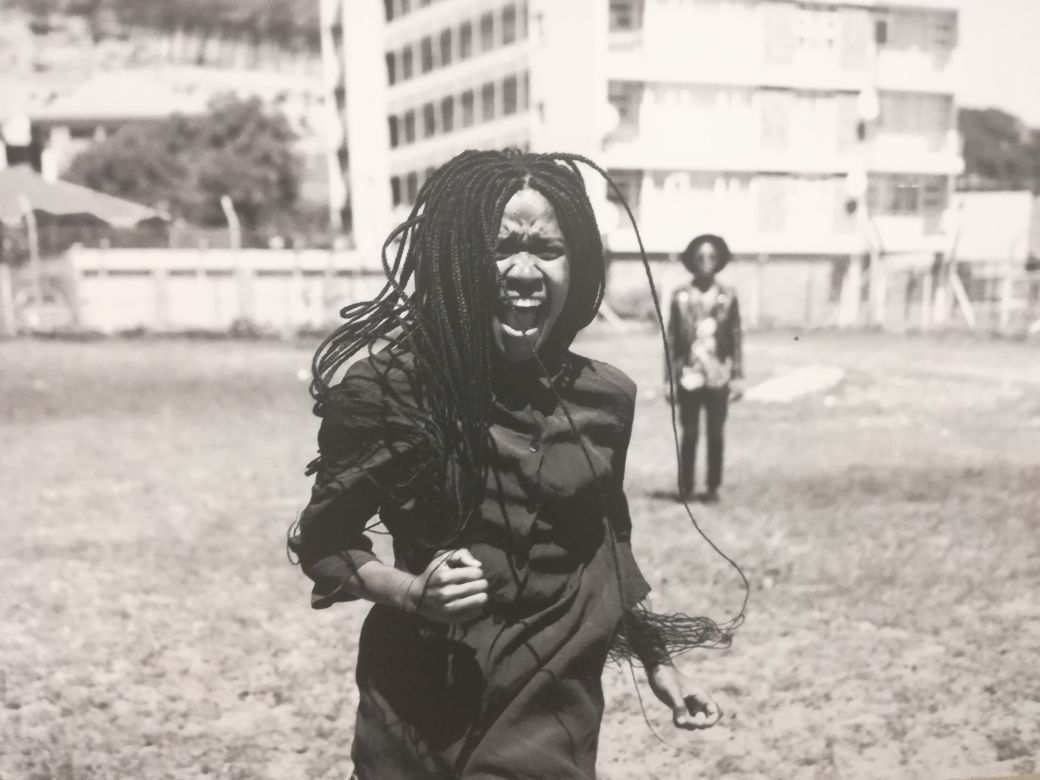

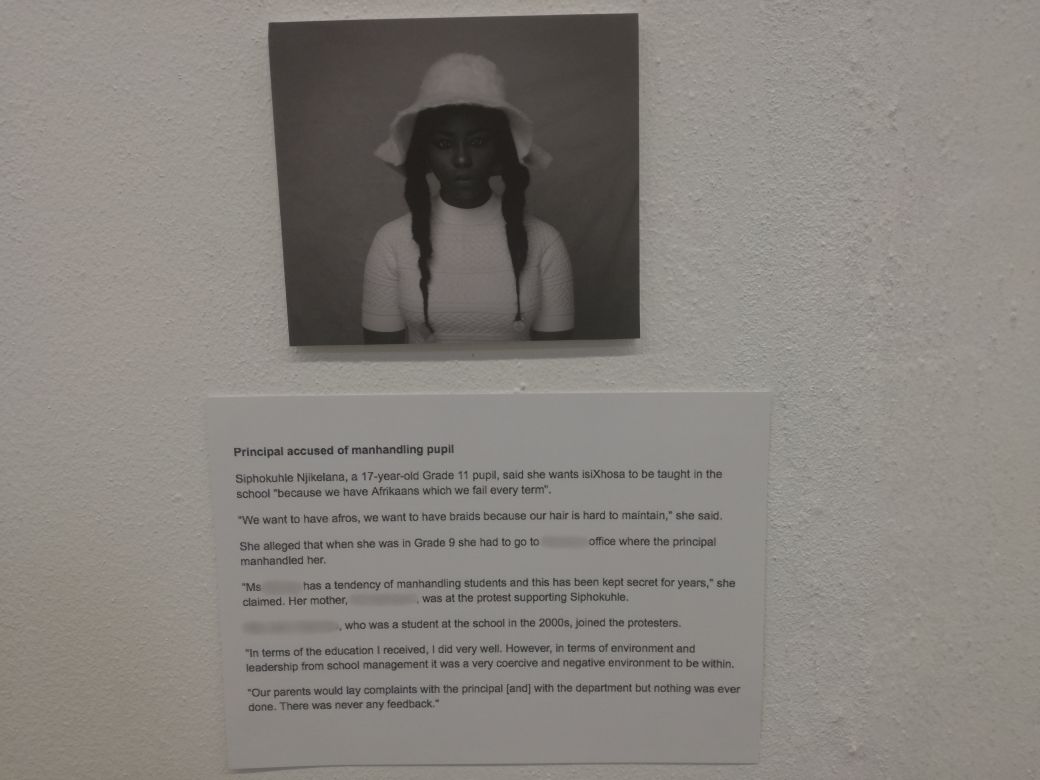

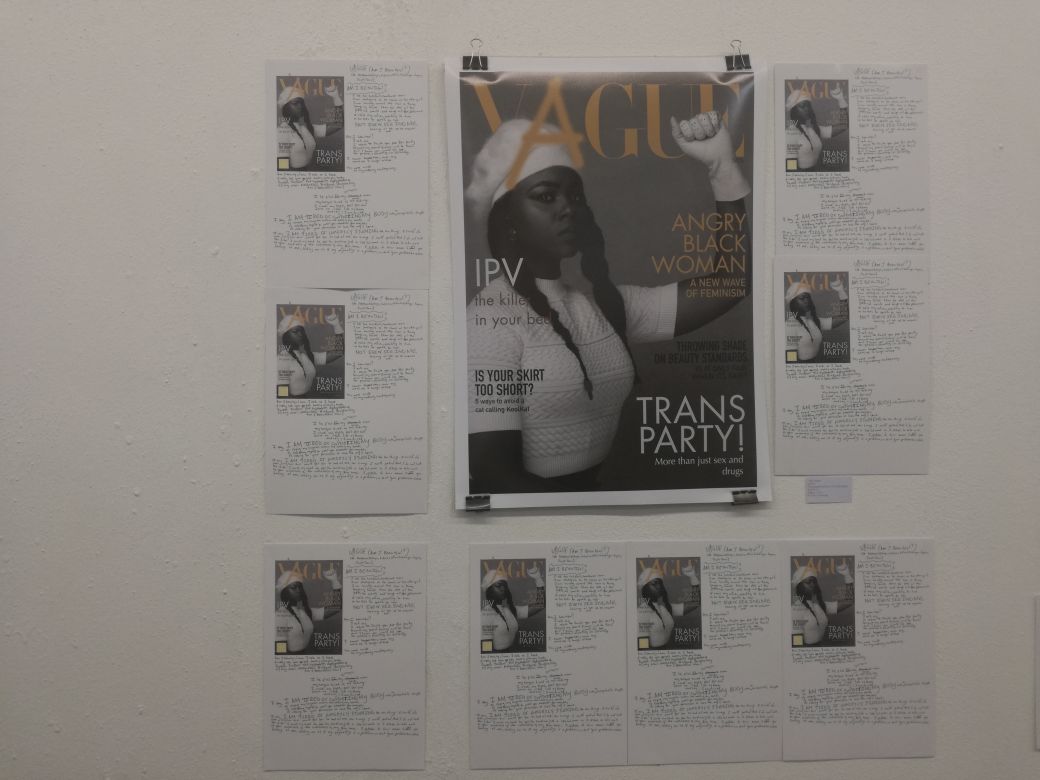

Resistance could be anything that subjugate your will to be free. I’m interested in looking at the idea of how brown femmes are considered to resist struggles or depicted in the media on things like femicide, interpersonal violence or domestic violence. It’s not necessarily toyi-toying in the street saying free education for all. Resistance is choosing your way over society’s way. A black women who stands up and says my brown skin is beautiful, that for me is resistance. You’re choosing your way. I choose self love as a form of resistance for a brown femme form because its seen as inferior to whiteness.

I’m trying to reframe the concept of resistance that stems from a sense of self love and just love in general for other brown femmes and for other human beings alike. That’s how I conceptualise the brown femme form’s resistance in the world – not this idea of angry people but this idea that we love so we are willing to die and fight for it.

I say femme instead of female because I’m trying to be inclusive of transwomen and males that consider themselves to be a she. A femme has nothing to do with gender, it has to do with how you perceive yourself as a person. Femininity and masculinity as concepts have nothing to do with gender. Gender is a social construct. I contextualise myself as a non-binary person, I don’t subscribe to the concept of a he or a she. Femininity and masculinity for me are energy concepts. It has everything to do with the state of mind, a level of consciousness as opposed to the physical mind. They exist on a spectrum where femininity has more to do with creativity and masculinity with those things that are more structural. I’m trying to frame femininity in this context as a shade of love that we should all aspire to.

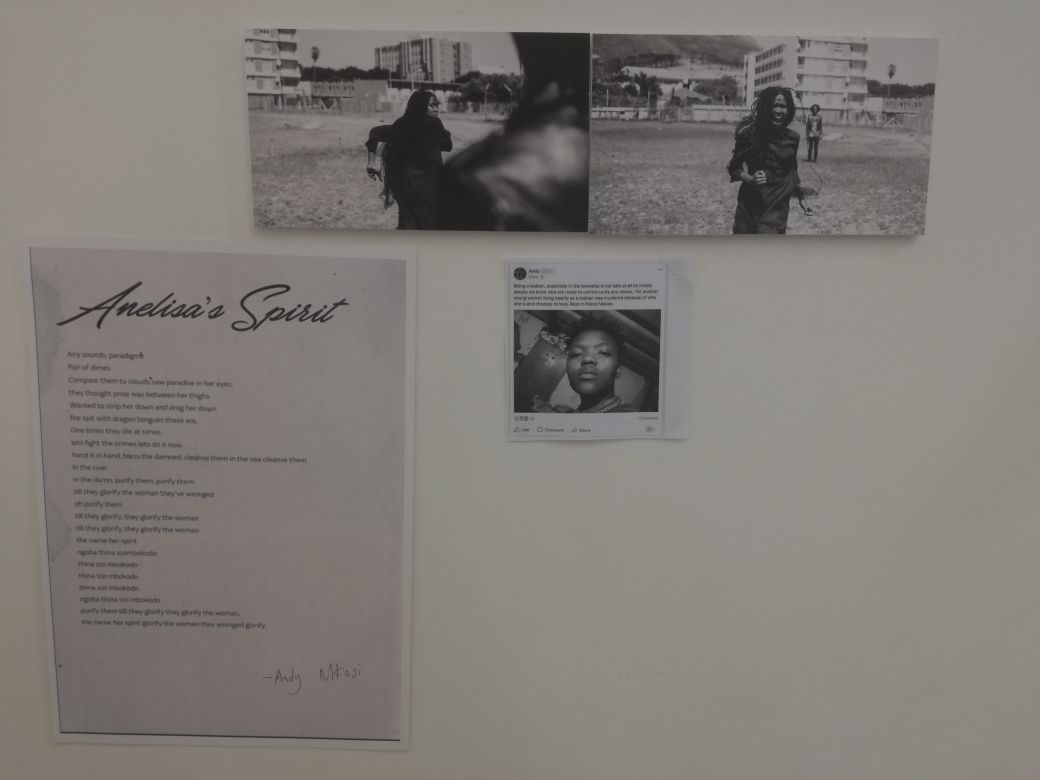

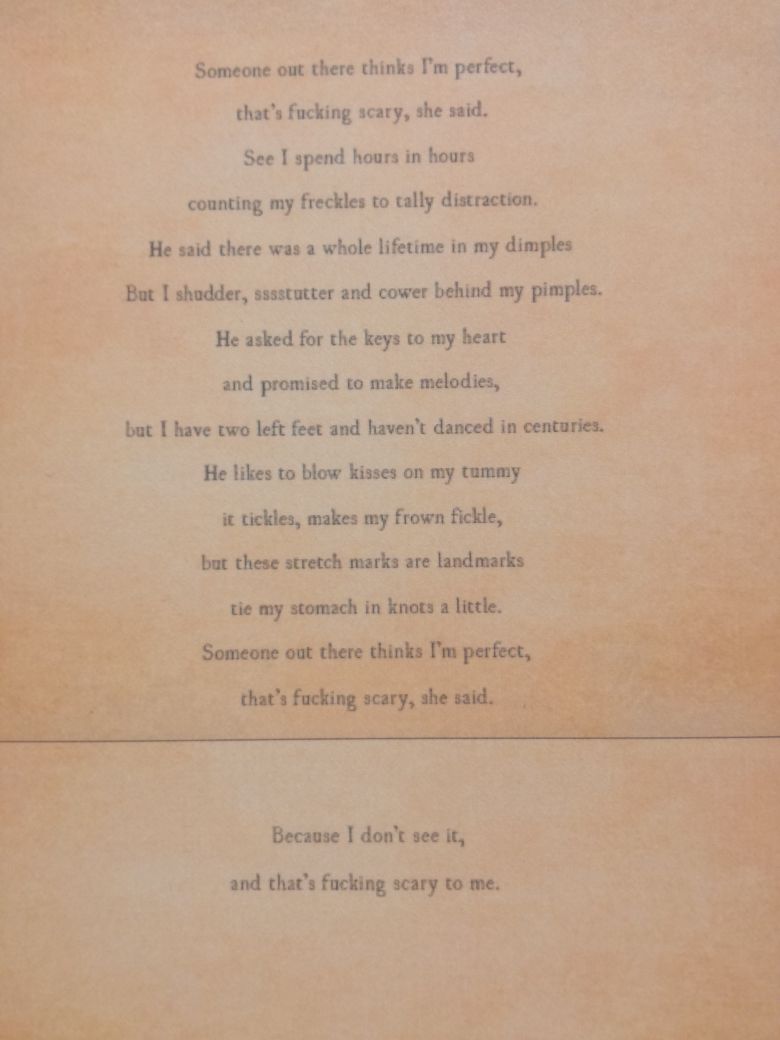

Every single one of those women in the recordings – the conversations you hear in the audio were sent to me as voice recordings and voice notes which I’ve recreated (not Nina Simone of course) – the photographs are all my friends, my family. The recordings femmes are speaking to frivolous shit, political stuff, about everything. Males do that too but why do we think it’s so different? We’re having the same conversations, we have the same aspirations. All the poems and photographs that I’ve chosen are based on the conversations in the recordings. The headlines on the cover image, the vague cover image, those are topics that are being negated in mainstream media.

I’ve spoken in depth with the women in my art about femme identity, that’s where I get a lot of my understanding barring the fact that I was only raised by women as well. It doesn’t give me the leeway to be empathetic about femme identity. I can other be sympathetic about it because I don’t really understand what it’s like to be a woman, I can only understand from a human point of view. If someone says they were bullied in school for the colour of their skin, I could relate to that but if someone says men were catcalling me in the street I could never relate to that because as a male I’ve had the privilege of not being catcalled in the street.

I’m using my presence as a male black body – which is often seen as a destructive force – as a constructive force. I am part of the problem, I’d like to be part of the solution. You can’t have a conversation about femicide without speaking of the preconditioning of young men to be violent. As a black male body, I’m being conditioned to hate you but I’m trying to love you. If I’m not being destructive in the conversation, I don’t see how I’m consuming the brown femme experience.

What calmed my anxieties of being a black male form photographing brown femmes is how I saw them. How I captured them showed me how I thought about them – in a tenderness, a gentleness, as royalty. That helped me think it wasn’t that bad to be part of the conversation as a black male body.

Lizamore & Associates is currently showcasing three photographic solo exhibitions by Manyatsa Monyamane, Justin Dingwall and Tsoku Maela – all interrogating socio-political issues around brown and black female identity. The exhibition opened on 1 March and will run until 28 March 2018.