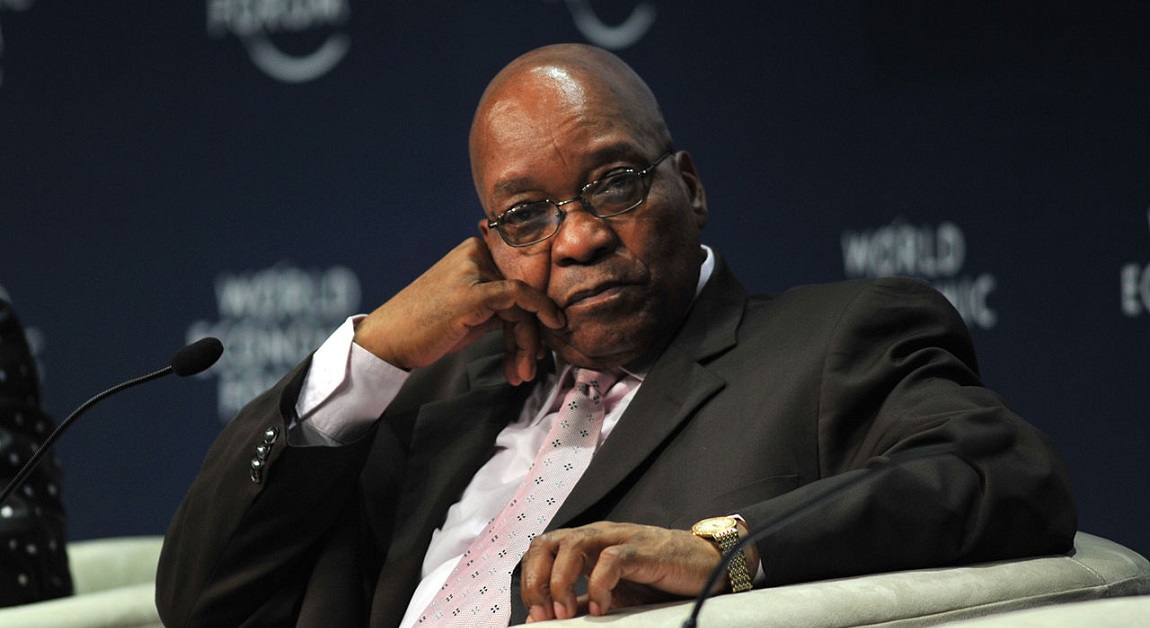

On 14 September, the Supreme Court of Appeal finally heard an appeal which will decide whether the corruption charges against President Jacob Zuma will be reinstated. But how significant is this appeal? Safura Abdool Karim explains.Â

In April 2009, then-acting head of the National Prosecuting Authority (NPA), Mokotedi Mpshe made the decision to withdraw over 700 charges of corruption against Zuma. The Democratic Alliance appealed this and in April 2016 the High Court in Pretoria found that Mpshe’s decision was irrational and invalidated it.

The effect of this ruling was to reinstate the charges against Zuma as if they had never been withdrawn. However, no prosecution was forthcoming. The NPA appealed the High Court’s decision first at the High Court (which was dismissed) and then at the Supreme Court of Appeal.

The NPA and Zuma’s appeals dealt with two questions. The first was whether the decision to withdraw the corruption charges was invalid and secondly, if it was, what should happen to the charges.

During the hearing last week, counsel for the NPA, Advocate Hilton Epstein argued that Mpshe’s decision was not invalid on two grounds. The first argument was that the charges and the entire prosecutorial process against Zuma had been tainted by political interference.

The political interference relied on was a transcript of a tape which showed that Leonard McCarthy, while heard of the Scorpions, had influenced the timing of the charges against Zuma in an effort to ensure Thabo Mbeki would be elected president of the ANC at the party’s 2007 Polokwane conference.

However, questions from the judges, and eventual concession from the lawyers involved, indicated that this political interference was not enough to invalidate the entire prosecution of President Zuma.

The second argument was around whether Mpshe had the authority to withdraw the charges. It was agreed that Mpshe had relied on the wrong legislation when withdrawing the charges. Epstein initially argued that this mistake did not necessarily invalidate Mpshe’s decision.

During the hearing, after substantial probing from the court (particularly Justices Mahomed Navsa and Azhar Cachalia), Zuma’s counsel, Advocate Kemp J Kemp, conceded that Mpshe’s decision was irrational.

This concession, in practical terms, means that Zuma agrees that Mpshe’s decision was invalid and thus should have been set aside. After this, Epstein admitted that a previous decision from the Constitutional Court directly contradicted his arguments on Mpshe’s mistake.

These two concessions all but resolved the first question of whether Mpshe’s decision should be invalidated.

Following this, Kemp changed strategy, attempting to argue that even if the decision is invalid, the charges should not be reinstated automatically. Ordinarily, if a decision is set aside, it is as if the decision never took place. In this case, invalidating the withdrawal of the charges would mean that the charges would be reinstated.

However, Kemp argued that President Zuma should have the opportunity to make representations to the NPA and that the NPA should first decide on these representations before the charges could be reinstated. The NPA also argued against the SCA reinstating the charges, suggesting that there be some intermediary step, such as issuing summons, before the case against Zuma proceeds.

Under the National Prosecuting Authority Act, anyone who is charged with a crime can present reasons to a director of the NPA to motivate why the charges should be withdrawn and not proceed. It is important to note that under the Criminal Procedure Act, these representations and the decision to withdraw charges can happen any time before a trial commences.

This means that even if the corruption charges were reinstated by the SCA, Zuma would still have an opportunity to make representations. As a result, Kemp’s arguments to allow Zuma to make representations before the charges are reinstated make little sense from a legal standpoint.

However, from a political perspective, Kemp’s request makes slightly more sense. For starters, allowing representations would leave the decision of whether to charge Zuma in the hands of the NPA rather than allowing a court to decide. Beyond allowing the NPA to decide on whether charges should proceed, allowing representations to be made could also be used to delay the reinstatement of charges since Zuma would need to be afforded time to make them and the NPA would, in turn, then need time to decide on them. Given that eight years have passed since the charges were initially filed, there is a real possibility that the representations process will be used to delay the case against Zuma.

While it is possible that the SCAÂ will return the baton to the NPA for a decision to be made on whether the charges should be reinstated, it is unlikely.