Srinagar, Indian administered Kashmir – My home, Kashmir, was hit with the worst floods in 100 years when the Jhelum River broke its banks on 7 September this year. It was a month after the floods before I was able to get to Kashmir. At first it was impossible to reach my home as our suburb, Nowgam, was still under water and inaccessible. Later, I was involved in relief work from Delhi, where I now live, and felt I couldn’t leave with a job half done.

Even though I knew what the damage looked like from television and social media, nothing could prepare me for the scene I was faced with when I finally traveled home.

It is strange how deceptively normal the earth looks from the sky. Very little seemed out of place as I watched from the sky on my flight into Srinagar’s airport. But when we landed and I exited the airport, I could smell the devastation in the air. The flood waters had now mostly dried, leaving a trail of dust in its wake. The air was no longer perfumed by its freshness.

On the way to home, I saw dirty water marks on the walls of damaged houses; the cars were painted with dried sludge.

My friend dropped me off outside my home. When I finally opened the main gate, what I found was shocking and heartbreaking.

Our garden had been evergreen. Flowers, fruits and all kinds of vegetables used to welcome me. Now there was nothing but a trail of dust, mud and dirt that the floods had left behind.

The greenery was missing from the lawn, which was now colourless. The ground floor of the house was empty. Fungus had completely covered the interior walls. The rooms once furnished with carpets and rugs were bare and damp. The whole house told the story of the horror it had faced.

I could not bear to see my home like this and went straight to my room on the first floor. But I found it had been transformed into a store room, with household good stacked in corners and lying haphazardly on the floor. The flood had changed everything.

The next day I started working on an assignment for Al Jazeera.

I have done many stories before but this one was different. I wanted the world to know about the magnitude of the disaster that this flood had caused but I wanted it to be different. One story in particular left me heartbroken.

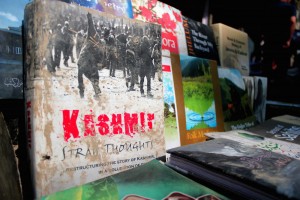

The books.

I visited Srinagar’s college libraries and book stores to find that the water had swamped over history and turned the pages into damp heaps of garbage. College and school libraries had lost tens of thousands, even hundreds of thousands, of books. It was unimaginable

At the library of one college, thousands of books were scattered across the floor, destroyed by the flood.

Kashmir was not only devastated economically; its history has also been tampered with. This realisation filled my heart with a deep sadness.

Pavements, roads, lawns, and drains were filled with disfigured manuscripts. It was difficult even to read their titles.

People desperately placed books full of mud and dirt out in the sun to dry. Many book sellers were now selling their damaged books on more than a 90% discount. One of the book sellers located in the heart of the city told people to take damaged books free of cost. He did it just to clean his shop.

I met a retired professor in Srinagar, who told me that we might rebuild the infrastructure in a century or so but we might have lost our history recorded in these books, forever.

While in Kashmir I heard heartbreaking stories, blissful stories, terrible ones and good stories first hand. The story of Kashmir’s lost books and lost histories is one of it’s many tragedies.

![Kashmir books [slider]](https://www.thedailyvox.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/Kashmir-books-slider.jpg)