Aubrey Matshiqi is a rockstar columnist, political analyst and researcher. He’s written a fantastic paper ahead of this year’s elections, on the false dichotomy between rationality and identity. It’s a mouthful, we know. So we read it for you, and here is our TL;DR version.

The filter bubble

You only have to look at this past weekend’s stadium wars aka final campaign rallies to understand the tendency to reduce voters’ views, interests and preferences to caricatures.

Voters, unlike what the party propaganda machines will tell you, are not simple beings, and their electioneering ignores the real complexity driving people’s politics.

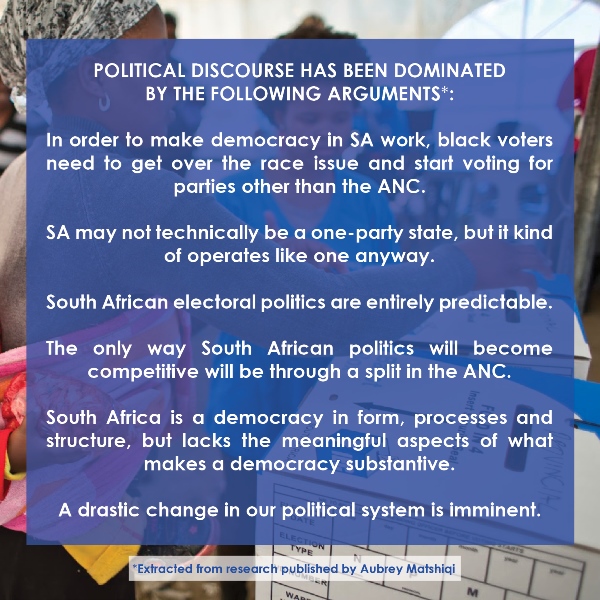

And here, we’ve got to fault what we call “political analysis” in South Africa. There is a tendency to draw on the same people, with the same world views. It’s sort of like how all your Facebook friends like the same stuff, so Facebook only brings you stuff in your newsfeed that it thinks you’ll like. It’s what the cool kids are calling the filter bubble.

Our exposure is restricted to people with similar thoughts, feelings, experiences and worldviews.

The more religiously devoted one becomes to these group sentiments, the less likely those views are to be critical or thoughtful. So what this then translates to in SA, is the formation of isolated groupings, with views that never fully engage with anything outside of it. Our political discourse then is sometimes thoughtless, lacking in nuance and complexity because it is never challenged or interrogated with exposure to fully developed contrarian views.

Please, don’t even

South Africans have been unable to imagine a future of SA without the ANC and DA. This has caused some to see the issue of our electoral politics as an “either/or” matter between the two parties and what they represent. Among these people are those who believe that the quality of SA’s democracy will improve the day most of the black population vote for the DA.

Related to this idea is the argument that ANC supporters vote with their hearts. The assumption is that a vote for the DA is a rational decision, rather than an emotive one.

But that argument misses the point because:

1. White voters kept the National Party, with increasing majorities, in power for forty-six years.

2. This means that for the past 68 years, South Africa has not had a strong opposition – of course we’re excluding the decades of struggle against white minority rule.

3. In the space of just a decade or three general elections, between 2004 and 2014, the ANC lost thirty seats in the National Assembly.

It’s cold outside the party

There is an over-reliance in South Africa on party politics.

The irony is that this may be one of the by-products of the “liberation movement model” approach to understanding current South African politics: the people are the “liberation movement” and the “liberation movement” is the people.

For the opposition, therefore, the only means by which change can be achieved is through the removal of the liberation movement – which in our democratic setting, is embodied by the ANC. This means that success in this narrative of the democratic project is dependent on opposition forces joining forces around the dominant opposition party – which is currently the DA.

Success, under this understanding, is about the alternation of power between two dominant parties fighting for control, over the same “motive force”. As the ANC argues, “the people”, particularly those who are not just “black in general” but are also “African in particular”, constitute the motive force for the National Democratic Revolution, of which the anti-apartheid struggle was simply one part of.

By limiting the legitimacy of the political sphere to party politics, efforts to push for social change through other means are often overlooked as realistic avenues for change.

The challenge for political parties then, is to avoid the error of thinking that those who vote for the ANC have a fixed identity and recognise the fact that politics in general, and electoral politics in particular, will be shaped by the evolving identities and complexities of citizens in their lives as voters and nonvoters.

![DA-RALLY-SOWETO-IH-19 [slider]](https://www.thedailyvox.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/DA-RALLY-SOWETO-IH-19-slider.jpg)