Beats of the Antonov documents the ongoing civil conflict between the Sudan Revolutionary Front and the Sudanese government in the Nuba Mountains and the Blue Nile, largely through the community’s relationship with music. The documentary, directed and produced by Hajooj Kuka, paints a vivid picture of culture and identity in times of war. Review by ANDREW KAGGWA.

Beats of the Antonov derives its name from the fighter planes we see dropping bombs on villages in the opening scene. The film begins by showing families running to take cover after their village is hit, then moves to depicting how people in the Blue Nile celebrate surviving death; in short, they laugh it off.

Before we fully get used to the situation, we are immediately immersed in the sounds of the people. We meet the village’s artists, hear their ambitions and aspirations, and learn why music means so much to them. While the war dictates the rhythm of their lives, the resilience of the community – and their music making – shines through.

The community is portrayed as one that has become used to the bombings; they are so much a part of the routine that they even wait for them – the youth sing and dance in the night as they wait for the planes to arrive on their bombing run.

“If a plane attacked while people are sleeping, it would be devastating,†says the narrator. But it is the music that keeps them alert throughout the night.

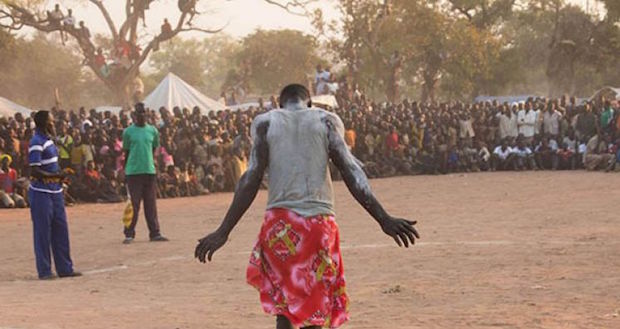

Kuka has said that the importance of using music, dance and laughter was to show the world that despite what Sudan has gone through, its people can still afford happiness. Their high-spirited resilience is depicted in most parts of the film – through the wrestling celebrations and various jam sessions where music comes from instruments made out of metallic pipes, saucepans and plastic bags.

The film doesn’t dwell on the fighting, but focuses rather on the way communities react to the crisis – in this case, through music.

Music is considered as tool of resistance against Arabisation that many people in the film blame on Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir in the north.

“Our songs are dedicated to the people of the blue Nile and all the displaced in Sudan from the Nuba Mountains to Darfur,†says a musician.

In one scene, Sarah Mohamed, a Sudanese ethnomusicologist notes that in Khartoum the identities they bare are fake but Blue Nile is the truth: “This is a Sudan that is happy and lives a normal life.â€