The UN has described the Ebola outbreak in West Africa as a “war†that might only be contained in six months’ time while Ebola exports and aid organisations like Doctors Without Borders (MSF) and the Samaritan’s Purse have weighed in calling the international response to Ebola a “failureâ€.

So, how has the international community – particularly the global North – responded to this “overwhelming crisis�

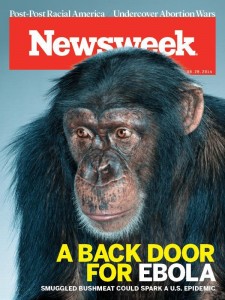

American magazine Newsweek drew ire for its cover story on Ebola which featured an image of a monkey with the headline: “A Back Door for Ebola: Smuggled Bushmeat Could Spark a U.S. Epidemicâ€.  The article claimed that America could be hit with an Ebola outbreak if “bushmeat†– such as chimpanzees – was smuggled into the country by African immigrants.

Evidently, the writer forgot to do his research. While rumours have circulated that game meat could be the source of the outbreak, these have so far been unfounded. Instead, what emerged was fearmongering, anti-immigrant bias and creeping racism.

“The authors of the piece andthe editorial decision to use chimpanzee imagery on the cover have placed Newsweek squarely in the center of a long and ugly tradition of treating Africans as savage animals and the African continent as a dirty, diseased place to be feared,†said the authors of a blog post on the Washington Post.

2. Giving Ebola the American treatment

Or at least giving Americans the Ebola treatment.

Never mind the thousands of Africans suffering from Ebola, two Americans and a Spanish priest were the first people to receive an experimental drug that could potentially cure Ebola. The Americans survived, but the priest died.

But the debate now is more about access to medication than anything else, namely, why did the Americans and the Spaniard have first choice of the drugs, when over 1 000 people living in Liberia, Sierra Leone, and Guinea have died from the disease since March?

An article in The Nation asks “What’s Behind the Media’s Ebola Sensationalism?†and challenges the media flurry that followed American doctor Kent Brantley as he returned to America for treatment.  Ultimately, despite the fact that the disease had been tearing through West Africa for months, Ebola only became Ebola when Americans were affected.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) has said administration of the experimental drug ZMapp was ethical so long as patients gave their informed consent, and some have argued that only health workers can give informed consent, because they fully understand the risks involved.

But even so, why wait for American health workers to get ill in August, when doctors in Africa have been dying since March?

Just over a week ago, two signs went up in a popular pub in Seoul, South Korea, banning Africans from entering the establishment – not just Africans from Guinnea, Liberia and Sierra Leone but anyone of African descent.

There was outrage on social media after an image of the signs was posted on Facebook. The picture went viral, and the pub owner – who put up the signs – was denounced as a racist in need of a reality check. In the end, the owner posted a new sign apologising for his actions and calling it “horribly inappropriateâ€.  Stigmatising an entire racial group is never a good business move.

4. Restricting flights to affected countries

As the outbreak continues its rampage, countries are bordering up to prevent the disease from seeping into their homes. Many countries around the African continent, including South Africa, Ivory Coast, and Kenya, have closed their borders to countries where the outbreak is centred. British Airways and Emirates Airlines have cancelled flights to Sierra Leone and Liberia, while 700 employees at Air France have petitioned the airline to get out of Sierra Leone and Guinea.

Flight restrictions to and from the affected countries are understandable, but also detrimental. Ebola is only communicable through infected animals or contact with a patient’s body fluids – it is not airborne - and flight restrictions are “not an optimal measure for controlling the import of Ebola virus diseaseâ€, according to the UN’s Stephane Dujarric.

Ultimately, flight restrictions are hampering the fight against the disease, as critically-needed medical supplies and health personnel cannot be transported to affected counties. They simply leave people wanting to leave or enter the affected countries nervously re-checking their flight plans.

5. Ignoring the real problem

In five months Ebola has killed 1,427 people in West Africa, and officials admit that this number may be “vastly underestimatedâ€. The WHO estimates that in each of the three epicentres of the outbreak – Sierra Leone, Guinea and Liberia – only two doctors are available to treat 100,000 patients. Already, 120 health workers have died, 240 more are infected, and prominent doctors who are thought to be experts on the disease have lost their lives. On Tuesday the WHO announced that is was removing its response teams from Sierra Leone after a health worker contracted the disease.

The Ebola outbreak has been made worse by “poor infrastructure, limited health research, and inadequate scientific advice†in the three affected regions, which means it’s probably a good time for more fortunate members of the international community to lend some support.

Last week, MSF’s Brice de la Vigne said the international community was more focused on protecting its own borders, than fighting the spread of the virus. “We are completely amazed by the lack of willingness and professionalism and co-ordination to tackle this epidemic. We have been screaming for months,†he said.

So the question now is, when will African lives start to matter?

![ebola cartoon [resized]](https://www.thedailyvox.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/ebola-cartoon-resized.jpg)