HIV/AIDS continues to be one of the greatest challenges of our time. Yet there is a sinister silence on HIV/AIDS in our public dialogue. Any real discussion about the lives of people with HIV/AIDS appears to be contained to conferences like the one currently underway in Durban.

The failure to prioritise a scaled-up response to HIV/AIDS in public policy is an indictment on our politics, yes, but it is also an indictment on a culture of the media that fails to reflect the reality of the world if it is not packaged neatly into a spectacle.

We cannot wait to be shocked into action. We cannot wait for searing images of suffering, or a rousing speech at this conference to jolt us out of complacency. We must understand that behind the statistics lie people living with HIV/AIDS. We must understand that behind the statistics lie people who have the right to quality healthcare.

And yet, 18 people die of Aids every hour in South Africa.

Read that again.

Eighteen people die of Aids every hour in South Africa.

And it’s not a uniquely South African problem.

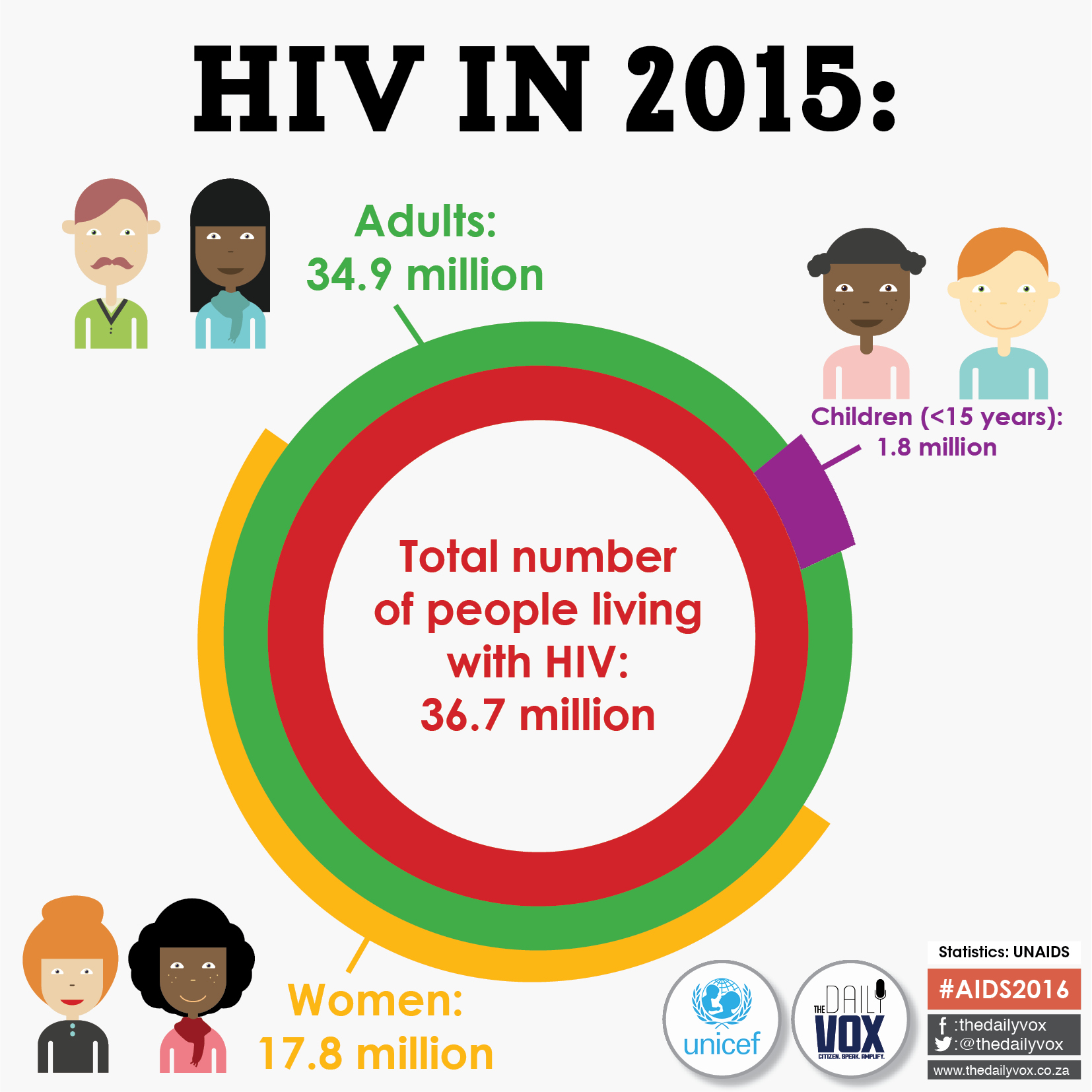

There are currently 37 million people living with HIV around the world.

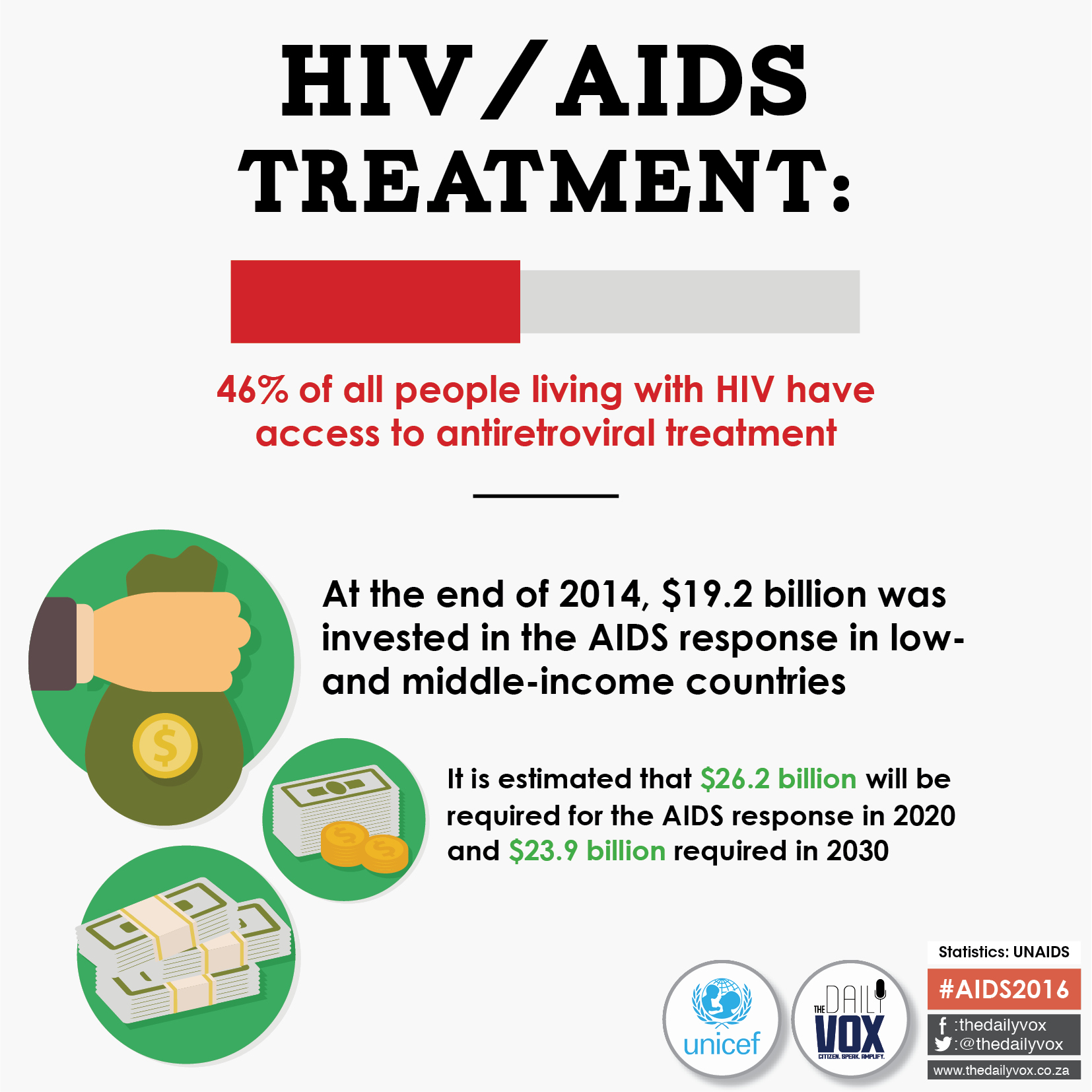

Of those 37 million people, 20 million do not have access to treatment.

And it’s not just bumbling African governments to be blamed here. There are also big pharmaceutical companies making obscene profits from the drugs that could save the lives of those living with HIV/AIDS who must share the responsibility here. Culpability must also be distributed to the donors who are scaling down their funding for the fight against HIV/AIDS.

But there is more here.

It is mostly poor, black people who are suffering on the margins with HIV/AIDS and its horrific consequences.

Yet we are force-fed a narrative that there is good news about Aids. What this has done is leave a slow burning massacre on the poor, the invisible and the apparently inconsequential populations of the world. It is these people, the young, black women, men who have sex with men, transgender people, sex workers, injected drug users and prison convicts, who are most at risk of contracting HIV. It is these people who are most likely to die of Aids-related causes.

Still, it appears we are waiting for the equivalent of an Aylan Kurdi to wash up on a European beach, with HIV+ tattooed to his arm, before we can admit that this is an emergency.

Addressing Aids in Africa, through the American PEPFAR initiative, has been effective. But it has always been about protecting the developed world from a mythical phantom in the guise of HIV/AIDS.

The new phantoms go by the names of: “terrorism”, “Muslims”, “refugees”. And so it turns out that the western world, or in particular the powers of US, France, UK, has moved on. And we, too, must move on. Hence the narrative must shift and adapt to accept that we have.

We cannot deny that progress against the pandemic has been made. Global health systems are responding better to the needs of people living with HIV/AIDS. But celebrations of these successes are premature.

The rate of new infections is said to have dropped. But have they really?

In 2015, around 2.1 million people became newly infected with HIV. It was 2.2 million in 2010. Sure, that’s a decrease of 6%. But let’s go over that again. A whole 2.1 million who didn’t have Aids before, contracted the disease last year. For an idea of scale, that’s the entire population of Botswana.

We can celebrate as well, the fact that fewer people are dying. This is great. Except that 1.1 million died from Aids-related causes in 2015. It was two million in 2005.

Let that sink it – 1.1 million people died from Aids-related causes last year. That is 1.1 million people too many.

Of course, other figures are more substantial.

New HIV infections among toddlers have decreased by more than half since 2010. But still, 150,000 children were infected with HIV last year.

We hail the fact that 17 million people living with AIDS worldwide are now on life-saving drugs. The problem, of course, is that there are another almost 37 million people living HIV and Aids across the globe.

And then we must ask, what about those who cannot possibly access the treatment? Do they merely go back to the queue and come try again next year? Not quite. They die.

In South Africa, there are some 3,5 million people on antiretroviral (ARV) treatment. Sixteen years ago, when the conference first came to the African continent (by way of Durban, South Africa) only those with money could access the treatment. Again, there are another 3 million South Africans living with HIV who are yet to access the treatment.

It is an issue the Treatment Action Campaign (TAC) has brought up repeatedly since treatment introduced in 2004. On Monday, they raised it again, when 10,000 people took to the streets of Durban to demand equal treatment. And on Tuesday, Mark Heywood, the co-founder of TAC, told journalists the TAC were demanding a government roadmap that would detail how the others would access the medication.

We support the call from civil society for government to show us exactly how they will respond to the needs of the 3-million people living with Aids who do not have access to ARVs in South Africa.

Aids is not on its way out just yet.

It is irresponsible and cruel to suggest that HIV/AIDS is no longer an emergency. We refuse and resist. We demand treatment for all, and a re-prioritisation of the lives of people with HIV/AIDS.