Gender-based violence remains one of the biggest scourges in South African society. Everyday, women and gender nonconforming people live in fear of being victims and survivors of GBV. However, new legislation which was signed into law aims to prevent and bring an end to GBV. Here are some of the most important GBV legislation in South Africa.

Most recently, the president of South Africa, Cyril Ramaphosa signed into law legislation aimed at “strengthening efforts to end gender-based violence”. The laws and bills are the:

- Criminal Law (Sexual Offences and Related Matters) Amendment Act Amendment Bill

- Criminal and Related Matters Amendment Bill

- Domestic Violence Amendment Bill

They emerged from the 2018 presidential summit against gender-based violence and femicide. During the summit, the declaration resolved that there was a need to address legislative gaps and fast-track all outstanding laws. From the summit, a national strategic plan on GBV and femicide was produced. It outlined the need for further policies and better implementation. The bills that were passed in parliament in July 2021 and signed into law in February 2022 were mentioned in the summit and plan.

RELATED:

At Gender-Based Violence Summit, Ramaphosa Calls For “Tangible Solutions”

New Bills

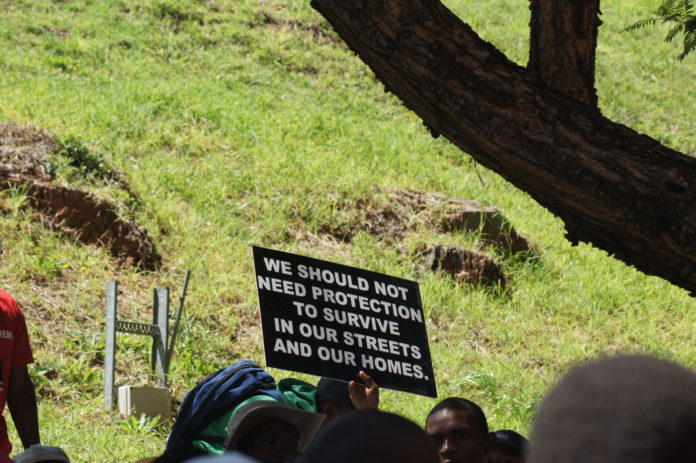

The three new amendment bills are meant to strengthen the country’s response to gender-based violence. They were first introduced to parliament following the rape and murder of Uyinene Mrwetyana in August 2019. There were national protests following her death, which called on the government to take gender-based violence more seriously.

READ MORE:

There Are No Longer Spaces For Us To Feel Safe

The Criminal Law (Sexual Offences and Related Matters) Amendment Act Amendment Bill amends Chapter 6 of the Criminal Law (Sexual Offences and Related Matters) Amendment Act. It aims to expand the scope of the national register for sex offenders (NRSO). It will expand the list of people who are to be protected. The act aims to increase the periods for which a sex offender’s particulars must remain on the NRSO before they can be removed from the register.

The Criminal and Related Matters Amendment Billamends the Magistrates’ Courts Act, 1944.It is supposed to provide for the appointment of intermediaries and the giving of evidence through intermediaries in proceedings other than criminal proceedings. The bill further aims to regulate the granting and cancellation of bail. It aims to provide for additional procedures to reduce secondary victimisation of vulnerable persons in court proceedings.

In 2021, the bills were still being considered by parliament. At the time, Bernadine Bachar, director at the Saartjie Baartman Centre for Women and Children, spoke to The Daily Vox. She said she doubted the efficacy of many of the proposed amendments. Bachar said she believed that not enough consideration has been made for potential consequences of these bills being passed.

READ MORE:

Gender Based Violence law amendments could do more harm

Finally, the Domestic Violence Amendment Bill amends the Domestic Violence Act 116 of 1998. The amendments are to address practical challenges, gaps and anomalies which have manifested since the act came into operation in December 1999. The amendments include new definitions of and expands on existing definitions. Furthermore, the bill introduces online applications for protection orders.

During the announcement by the president, Ramaphosa said: “The enactment of legislation that protects victims of abuse and make it more difficult for perpetrators to escape justice, is a major step forward in our efforts against this epidemic and in placing the rights and needs of victims at the centre of our interventions.”

Other Bills and laws around GBV

With many laws and legislations, South Africa has often been hailed as very progressive. For example the constitution is seen as one of the most progressive in the world. The laws and legislation around the LGBTQIA+ community are also seen as very forward-thinking.

Read more:

Our progressive constitution is not enough to protect LGBTQIA+ people

South Africa’s government has ratified the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights (African Charter) and the Protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights on the Rights of Women in Africa (the Maputo Protocol) and the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW). Along with ratifying these international and continental charters, the government has passed national laws which ensure the domestic laws align with the international laws. These include the 1998 Domestic Violence Act, the 2012 Criminal Law (Sexual Offences and Related Matters) Amendment Act, the 1998 Maintenance Act, and the 2011 Protection from Harassment Act.

The Domestic Violence Act of 1998 according to Smythe (2009), is considered to be one of the most inclusive and progressive pieces of legislation. This is because it recognises a wide range of GBV, it acknowledges that GBV can occur in a variety of familial and domestic relationships and it gives magistrates power to serve abusers with court orders.

The Criminal Law (Sexual Offenses and Related Matters) Act of 2007, handles all legal aspects of or related sexual offenses and crimes under one statute. It is supposed to regulate all procedures, defences, and evidentiary rules in prosecution and adjudication of all sexual offenses. It also criminalises any form of sexual penetration, sexual violation without consent, irrespective of the gender of the victim.

However, even with these progressive acts, it is noted in an academic paper that “the acts do not provide strategies that take into consideration or counter cultural, social, and economic factors as the forces within which VAW is embedded”. This along with several other reasons outline the shortcomings of these laws.

Despite these laws, women and gender nonconforming people and other marginalised communities continue to face violence. This is because a huge gap exists between the legislation and the implementation. Another element is that even when there is the political will, there is a lack of funding. The government might have these policies and laws in place but do not provide the funding to ensure these services are adequately carried out.

While shelters are available for victims and survivors of GBV, these services are often underfunded and under resourced. This was seen during the lockdown where the government didn’t provide funding for these services. This meant that many women were in lockdown with their abusers as there wasn’t anywhere else for them to go. Additionally, even as restrictions eased, the situation didn’t improve as the government didn’t prioritise funding. Important policies were also not finalised which shows how there are many gaps and limitations to having progressive legislation on paper. and

READ MORE:

Lockdown Could Mean Women Are Trapped Indoors With Their Abusers

Featured image via