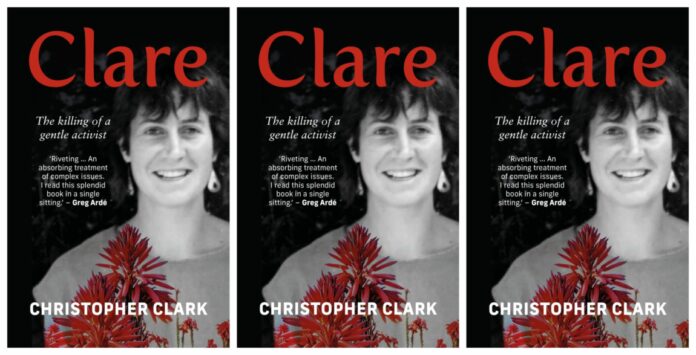

Clare: The killing of a gentle activist by Christopher Clark is the story of Clare Stewart. Clare Stewart was a much-loved ANC activist and rural development worker who was found murdered in KwaZulu Natal in 1993. When journalist Christopher Clark stumbled upon Clare’s story, it would not let him go. This is his account of the search for the truth about Clare’s killing, and his quest to better understand both her bold, intrepid life and her enduring legacy.

An extract from the book has been republished below with permission from the publishers.

Red aloes

I sent Themba a message of introduction the next day. True to her word, Puleng had already spoken with him. ‘I’m fine to speak,’ he messaged back.

We arranged to meet for lunch at a quiet and eccentric bar called A Touch of Madness in the artsy suburb of Observatory, where Themba worked as a production and venue manager for the small, youth-oriented Magnet Theatre.

As was often the case, I underestimated the perpetually terrible traffic on the M3 heading into town from Muizenberg and arrived about fifteen minutes late. Feeling slightly flustered, I walked through the old Victorian building and out onto the leafy terrace at the back to find Themba sitting cross-legged at one of the tables, smoking a cigarette in the winter sunlight.

As he stood to shake my hand, there seemed to be an intrinsic, calm self-assurance about his movements and his general demeanour. But he also immediately struck me as more withheld than Puleng, as someone who is innately aware of how much of themselves they reveal to others – particularly, I imagined, strangers like me, who were eager to dig into their past.

I had a notepad and voice recorder and placed them beside me on the table, but what followed over the next hour felt more as though Themba were interviewing me than the other way around. He asked me a series of keenly considered questions about why and what I wanted to write about his mother. I fumbled my way through the conversation in an embarrassingly waffling fashion while anxiously puffing on a cigarette I’d scrounged from him in an attempt to build rapport.

I could understand his guardedness. To a greater extent than Puleng, Clare’s story, and her trauma, were also his own. He had travelled around South Africa with her; he knew the feeling of being sent away to boarding school and pining for her; he had witnessed her rape; he had been old enough to register the rupture that followed her death. It was undeniably easier for Puleng to have a certain detached curiosity about their mother than it

was for Themba.

As an intelligent and socially conscious storyteller himself, Themba had reasonable concerns about whether I was the right person to tell this particular story, in all its nuance and complexity. ‘No offense,’ he said, fixing me with his deep brown eyes, ‘but you are a white man and you don’t speak Zulu. There are going to be things that you will not be able to fully understand or articulate about the world which Clare inhabited.’

I didn’t disagree with him. I often grappled with such concerns, as a foreign, English-speaking journalist, in a country where language was so heavily laden with a history of racism and division, and where so much could be lost in translation. Often, when I was interviewing a black Zulu, Xhosa, Sotho or Tswana speaker, I found myself wondering how my identity influenced what they were telling me and the manner in which they told it. What kind of story did they think I wanted to hear? What kind of picture did they want to paint? How much control did they feel they had over their own narrative? And in what ways would this differ if I spoke the same language, or had the same colour skin, or came from the same community?

I had come to accept that any single version of anyone’s story was always and inevitably going to be lacking in some way, whoever was extracting it from them. Nevertheless, I told Themba that I believed I could still at least fill in some of the gaps in Clare’s story, and that I also felt it would add nuance to the country’s narrative.

Themba gradually warmed to me as we spoke, and by the time we said goodbye he had agreed to act as an initial conduit between me and Clare’s siblings, who, he said, would be the gatekeepers of her story, at least from a familial perspective.

A few weeks later, Themba forwarded me a short email thread between himself, Rachel, John and Peter. I felt simultaneously flattered and condescended to, on seeing that Themba, more than a year my junior, had referred to me as a ‘young investigative journalist’. But the general response from Clare’s siblings was encouraging. ‘This looks positive,’ wrote John in the perfunctory epistolary style that I would come to learn was shared by all Clare’s older siblings.

***

It was another three months before Themba and I met up again. Just a few days after our first meeting, he went away on a three-week tour with a Magnet production to Japan, and I struggled to tie him down when he returned to Cape Town. Not wanting to pester him too much, I’d turned my own attention to a few other projects that took me back on the road for a while, first in Gauteng and then in North West. Afterwards, I took a few weeks off, and Thola and I got married on a rustic riverside farm in the picturesque Breede Valley.

Themba and I finally met in early January 2019, as Cape Town was emerging from the festive season. On a baking summer afternoon, I walked up the steep hill from my flat to meet him in his Lakeside home, where we sat in the shade on the balcony, drank Rooibos tea, and smoked a few of the cigarettes that I’d bought to repay him.

After a brief catch-up, Themba brought out a tattered Southern Comfort box full of documennts pertaining to Clare’s abduction and murder, including copies of the police and TRC reports and the hundreds of Amnesty International letters from all over the world. The box also contained Anne Hope’s unpublished ‘To Kill a Laughing Dove’. On the front cover of the ring-bound manuscript was a picture of Clare with a young Themba on her lap, his arms raised above his head and looped around the back of his smiling mother’s neck.

Themba told me that Anne had entrusted the box to him shortly before her death in December 2015; he was now passing it on to me. ‘I knew nothing of its existence before Anne gave it to me. It came out of nowhere and it kind of threw me off balance,’ he said. ‘My mother’s death is obviously something I’ve known about my whole life, but I never actually had that much information about it, so I initially became a little obsessed. But then I got to a point of saturation, where I wasn’t sure I wanted to know more. You know, there are some memories you want to keep and there are some memories you want to let lie.’

By his own admission, up until that point, Themba had spent much of his life trying to distance himself from the memory of his mother. ‘I built particular walls and coping mechanisms. I was just defending my emotional self,’ he said.

He had also been preoccupied with trying to adapt to a procession of new environments, as he moved from Manguzi to Johannesburg with Rachel, then to Zimbabwe with John and Kathy.

‘The thing about moving families often is that you have to learn to assimilate. You become adept at just moving on and shutting out stuff, so I gradually stopped thinking about Clare as time went on,’ Themba told me.

In Zimbabwe, he was enrolled in a strict Jesuit boys’ school, where the regimented conformity stood in stark contrast to the freedom of his years with Clare in Manguzi, and with the similarly progressive and pacifist leanings of her brother John. ‘I couldn’t handle that kind of school system at all, so I used to rebel a lot,’ Themba said matter-of-factly. ‘But I think I was also still just kind of silently withdrawing myself.’

At the same time, he inevitably grew apart from Puleng. Completely inseparable when Puleng was little, the two siblings then only saw each other once or twice a year for a couple of weeks during school holidays.

Published by Tafelberg, the book is available online and at all good bookstores.