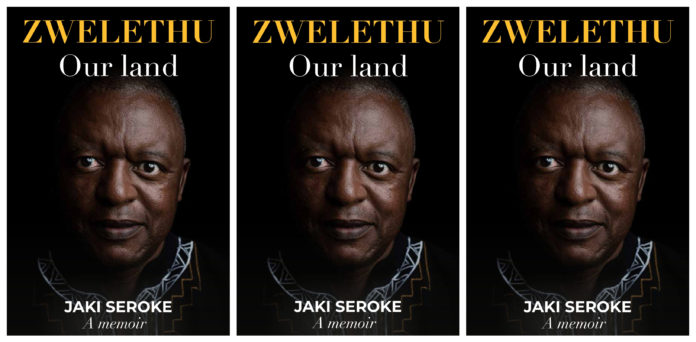

In his memoir, Zwelethu Our Land, Jaki Seroke shares the joys and the sorrows of his life. He recalls the political battles among the various Africanist groupings, his incarceration on the Island and his later work at Skotaville Press, as publisher and poet. After 1994, he joined the corporate sector and committed to a new kind of struggle – that of economic transformation in ‘our land’.

An extract from his book has been republished below with permission of NB Publishers.

Serve, Suffer and Sacrifice

I was now living dangerously. As a sworn enemy of the apartheid and settler state, I could be taken out in the ‘total onslaught’ battle that President PW Botha was conducting. It went without saying that the liberation movements in exile and at home were heavily infiltrated by enemy agents. I was a nobody. I could be whisked away in a flash and nobody would notice that a nobody was no more. You did not have to be important to feel vulnerable to elimination.

The possibility of arrest and a long time in prison was now very real. Being recalled by the mission in exile of the Pan Africanist Congress of Azania was also possible, as was being abducted by the progressive forces for my own good. It had happened in Zimbabwe, where a prominent journalist in the struggle for Zimbabwe was taken against his will by Zimbabwe African National Liberation Army guerrillas from his ranch while he visited his family. The intention was to protect him from imminent arrest by the Rhodesian security forces.

RELATED

Jaki Seroke, PAC Stalwart: “The Struggle Can Only Be Led By The African People”

My sixth sense told me repeatedly that I would be gone (detained or dead) by the year 1988. It was a feeling I couldn’t shake, but I told no-one about my fears. They would’ve said I was crazy to make such predictions about my own life. But I trusted my instincts. In analysing what had happened to me, I found that I did well in odd-numbered years and badly in even-numbered years.

Compared with Tlhaki I was a free man, without a wife and babies. He had truly lived dangerously, even using his work vehicle to travel to Gaborone and Maseru.

I was susceptible to falling in love with beautiful, innocent girls who had an honest goal to have children and form a stable family. How would I fit in with those dreams? I was an activist for political change. Dangerous. I was in the underground. Very dangerous. I had voluntarily taken on these commitments.

RELATED

Cyril Ramaphosa Should Listen To Robert Mangaliso Sobukwe

I was attracted to a pretty high school girl with freckles and a disarming smile who lived in the neighbourhood – Stokwana Kekana. I was chivalrous and walked her to the stores when she needed to shop. I made small talk with her to make her feel protected and safe. The ghetto had its two-legged beasts who forced themselves into the skirts of beautiful girls, jeopardising their education with teenage pregnancy and leaving them on the shelf afterwards. I was going to take it step by step with her. After a few days I mentioned that in the fairy tale Beauty and the Beast, Beauty grows fond of the Beast because he was caring and friendly. Eventually she falls in love with the Beast and he becomes a fine young man. A prince of peace. I would like to think that she grasped the message in my version of the story, because we were soon an ‘item’. I serenaded her with poetry and my own dizzy philosophies of life.

Stokwana lived with her brother at his house. He did his best to keep us apart, by rebuking her when I took her back home after an outing. Tragically, though, he committed suicide, leaving a wife and children. No-one seemed to know what had been troubling him. While Stokwana dealt with this emotional trauma, the struggle sucked me in. Our relationship petered out.

I was then at a new publishing house, Skotaville Publishers, in its editorial section. The African Writers Association had takena resolution to start a black-owned publishing house. Mothobi suggested the name Skotaville Publishers, after Mweli Trevor Skota. He’d been an advocate of African nationalism, and while secretary-general of the South African Native National Congress in 1933, had insisted on the name change to African National Congress. As a chronicler of events, he published The African Yearly Register.

One of the first titles we produced was Don Mattera’s Azanian Love Song, a collection of poetry. His banning order was about to end, and we planned to publish it on the day it expired. He agreed to this, and readily gave me his collection. Fikile Magadlela worked on the artwork for the cover design. Bra Don, as we fondly called him, was good to me. He introduced me to Wednesday only movies in Fordsburg, where they showed art-house movies. I came to learn all the elements of fiction and literary devices, such as allegory, flashbacks, cameo appearances, powerful diction, and dramatic performance. We would analyse all such issues while we watched these artistic feature films.

The publication of Azanian Love Songs was a great success, and as our first book did exceptionally well. The initial print run of three thousand copies quickly sold out, and we had to reprint.

We also published a collection of speeches and sermons, Hope and Suffering, by Bishop Desmond Tutu. At the time he was the dynamic secretary-general of the South African Council of Churches. This was by far the best publication, in terms of sales, that Skotaville produced. Altogether, the reprints must have totalled fifteen thousand copies. We also sold translation rights to many countries, which put Skotaville on the map.

There were other notable books, too. For example, we published a book on the social history of the Kagiso Trust by Eric Molobi, who was an executive member of the United Democratic Front. I also procured manuscripts from Catholic liberation theologists, such as Father Albert Nolan, who co-ordinated the production of the Kairos Document with the new South African Council of Churches secretary-general, Rev Frank Chikane. We worked on this document while they were both on the run from the Security Branch and from possible detention under the emergency laws. We also published a collection of essays edited by Charles Villa-Vicencio, which showed that we were not isolated from the broader struggle literature. My PAC work helped, rather than hindered, the spread of ideas as a challenge to the apartheid authorities.

There were interesting sideshows too. When it was clear that Bra Don would not be banned again, we were invited to art gatherings with him. One was at Nadine Gordimer’s Parkview house. There must have almost 30 leaders of the arts invited to talk to Hungarian billionaire and patron of the arts, George Soros. Everyone made a case for him supporting their art institution.

Don also took the opportunity to speak, and he criticised the mostly white and liberal participants for being hypocrites. He also spoke directly to Soros: ‘You have brought us sorrow, Mr Soros. We are all trying to outshine each other to get access to your money. I thank the host for calling the meeting, but I will not bow to this shame.’ I followed behind him as he walked out.

The African Writers Association also held writers’ workshops for beginners, and published the lecture notes of Es’kia Mphahlele on drama, fiction and poetry. Novelist Njabulo Ndebele mentored short-story writers at writing clinics we held at Wits University. We also had an extension programme with the National University of Lesotho, where a team went to interact with the likes of Zakes Mda and Sipho Sepamla. During this period I edited several issues of New Classic, a literary magazine first published as The Classic by 1950s Drum writer Nat Nakasa. Sepamla had reintroduced it as New Classic in the 1970s, and the African Writers Association published it in the 1980s.

Skotaville published on topical issues, starting with black theologians, political philosophies, and history. We also attended the international book fair in Frankfurt and the International Book Fair of Radical Black and Third World Books, organised by John La Rose, in London. In southern Africa, the Zimbabwe International Book Fair was a great attraction.

I used these opportunities to travel as a cover to do PAC work. I Interacted with most of the leaders. Mike Ngila Muendane was the secretary for labour. He assisted in connecting the above-ground activities on the labour front with PAC-supporting solidarity groups in Europe. The purveyors of Marxism-Leninism and Mao Zedong Thought in Belgium sent their labour unit to South Africa. We had them interact with the labour-union leaders in workshops at Wilgespruit Fellowship Centre in Roodepoort. Reverend Dale White, who ran the centre, was well disposed towards the PAC.

As part of our contribution to the unity project with the Black Consciousness

organisations, the PAC supported the National Forum Conference held at Hammanskraal in 1983. I was assigned a role in the arts and culture section, led by Benjy Francis and Zakes Mofokeng, and I chaired the evening programme, which featured play and poetry readings. I also published the conference papers with funding from the exiled PAC. The National Forum

was convened by Saths Cooper, who was a leader of the Azanian People’s Organisation. He had been one of the accused during the lengthy trial involving the Black People’s Convention and the South African Students’ Organisation, which led to his imprisonment on Robben Island for many years.