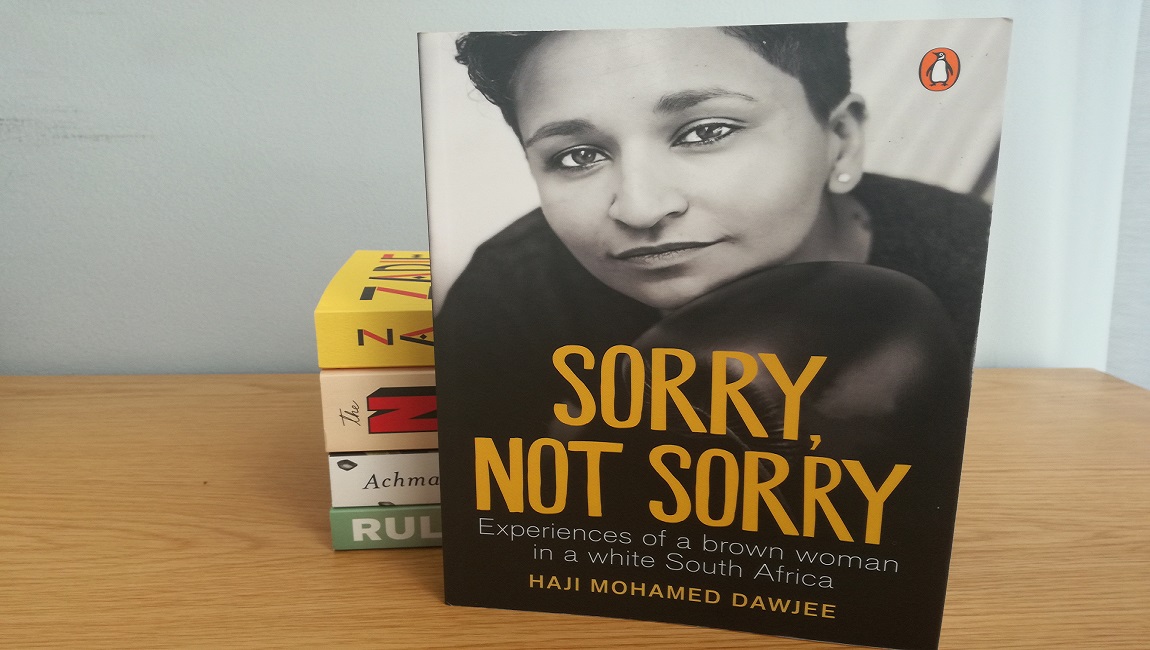

The title of Black Consciousness leader Steve Biko’s compilation of writings called I Write What I Like has become a slogan of sorts. It is influential in conversations about racism, post-colonialism, and black nationalism. But more than that, it’s a rebellious statement underpinned by the idea of choice. It’s about writing what you like, plain and simple. South Africans of colour don’t really write what we like, Haji Mohamed Dawjee says in her book Sorry Not Sorry: Experience of a brown woman in a white South Africa. Not like white men.

People of colour in South Africa own the narrative about struggle and hardship – which is really necessary in a country like South Africa – but hardly about the good stuff: the once in a lifetime excursions involving buffets, hot air balloon rides, whatever. Writers of colour just aren’t afforded those kinds of opportunities – both experiencing them and writing about them. But Dawjee takes the opportunity to do just that in her book.

The book is a collection of essays about her experiences as woman of colour in post-apartheid South Africa. The book doesn’t skimp on struggle – it’s impossible for a brown woman to lead a life that isn’t coloured by some sort of discrimination. Dawjee writes about her feelings of inadequacy, her depression, and her numerous experiences of both casual and blatant racism from her rejection of a crush in primary school to a bar brawl in Cape Town with her brother. But she also dips her toes into the fun stuff and waxes lyrical about people of colour and their affliction for sneakers (including an extremely useful guide to cleaning Converse All Star tekkies) peculiar conversations she had with her neighbour at university, and her renegade grandfather.

Dawjee grew up in a Muslim family in the former Indian township of Laudium, Pretoria. As a well-known journalist and columnist, she was the first ever social media editor at the Mail and Guardian. Today, she writes columns for EWN, Women’s 24, and The Sunday Times among other publications. This is her first book – and hopefully not her last because Dawjee is a good storyteller.

As she writes in her book, there are two very important ingredients to great storytelling. The first is memory and the second is emotion. A good story, she writes, should teach you something about the person telling it, but also about yourself as the listener. Her book was relatable to me in a way that books never quite are to a Muslim women of Indian descent in South Africa. It was so refreshing to read from the perspective of someone who looks like me and was brought up in a similar way to me.

Perhaps one of my favourite essays in the book was the one called A Better Life With Bollywood. In it, Dawjee describes one of the films of my childhood Veer Zaara and then constructs an argument to defend Bollywood to its naysayers. But the paragraph that rings the most true for me is this about what the films mean to people of the Indian diaspora: “But for those who have never visited their country of origin or never again had a chance to return, Bollywood gives them the chance to wear their patriotic hearts on their sleeves. It’s the Bollywood movie that lets them escape the existential confusion of being an immigrant. It’s the Bollywood movie that, even for a couple of hours, from doing as the Romans do, and allows sixteen million people of the Indian diaspora to be consumed by the beating heart of their country as it pounds with yearning through their veins. It provides a connection to their traditions and roots, and reminds them that while they’ve left many things behind, they have brought a lot with them as well.”

As a Muslim woman and someone who considers herself a feminist, it was wonderful to read how Dawjee writes about Islam. In her essay ‘And how the women of Islam did slay’, she tells of the way the Prophet Muhammad’s wives Khadija and Bibi Ayesha slayed. Both were pioneers for women of their time with one being a warrior and commander of armies, a lawmaker and a scholar; and the other a single mother, a businesswoman, the first believer in Islam, and a philanthropist. She speaks of the way facts in Islam are kept as secrets to deny women their freedoms in exchange for their degradation and exploitation. She writes about her faith in a way that is critical of Muslim communities with selective teachings, particularly some of the communities in South Africa.

Mohamed Dawjee lends voice to a demographic whose stories are not readily told. She brings to life her experiences in a way that is unapologetic, funny, raw, and thoroughly entertaining. Her insight is provocative and valuable in greater conversations about women of colour navigating a South Africa still dripping in white privilege.

Sorry Not Sorry is available for purchase both online or at your local bookstore at between R160-R220.