In Nathaniel Rich’s Losing Earth he accounts for the past failures of politicians and others to stop climate change. Looking back at 1979, Rich tells the human story of climate change and how close governments came to signing binding treaties that would have saved the world. In Losing Earth, Rich provides context for what did – and didn’t – happen in the 1980s. More importantly, he looks at what those past failures mean in 2019.

The Daily Vox published an extract from Rich’s book.

If the prospect of a wholesale political conversion seems delusional, consider that we have solved, or at least endeavored far more seriously to solve, major social crises before, some of them existential in nature. When popular movements have managed to transform public opinion in a brief amount of time, forcing the passage of major legislation, they have done so on the strength of a moral claim that persuades enough voters to see the issue in human, rather than political, terms. We do not hesitate to summon moral arguments in debates about racial injustice, nuclear proliferation, gun violence, immigration, same-sex marriage, or the accelerating rate of mechanization. Yet the public discussion of climate change rarely ventures beyond political, economic, and legal considerations. If we speak about climate as only a political issue, it will suffer the fate of all political issues. If we speak about climate as only an economic issue, it will suffer the fate of all moral crises subjected to cost-benefit analysis.

The first requirement is to speak about the problem honestly: as a struggle for survival. This is the antithesis of the denialist approach. Once the stakes are precisely defined, the moral imperative is inescapable.

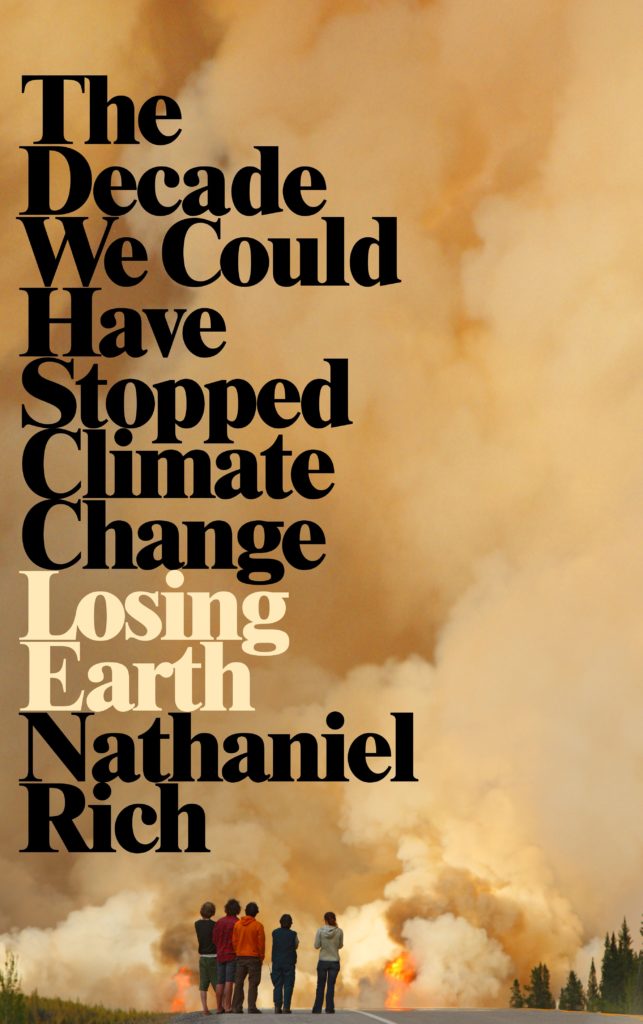

The cost-benefit analysis is rapidly shifting; the distant perils of climate change are no longer very distant. Many now occur regularly, flagrantly. Each superstorm and super fire is a premonition of more terrifying convulsions to come. But disasters alone will not revolutionize public opinion in the remaining time allotted to us. It is not enough to appeal to narrow self-interest; narrow self-interest, after all, is how we got here. Tens of millions of Americans who have no reason to believe that flames will lick at their patio doors or that floodwaters will surge up their driveways must still be moved to demand a full transformation of our energy system, our economy, ourselves.

The alternative is to wait for the suffering to become unbearable. Should we pursue the status quo for the next dozen years—the amount of time that the IPCC gives us to limit warming to 1.5 degrees—the fears of young people will continue to grow, in pace with the multiplying tragedies of a warming world. At some point, perhaps not very long from now, the fears of the young will overwhelm the fears of the old. Sometime later, the young will amass enough power to act. If we wait that long, there may be time yet to avoid the most apocalyptic scenarios, but little else.

Everything is changing about the natural world and everything must change about the way we conduct our lives. It is easy to complain that the problem is too vast, and each of us is too small. But there is one thing that each of us can do ourselves, in our own homes, at our own pace—something easier than taking out the recycling or turning down the thermostat, and something more valuable. We can call the threats to our future what they are. We can call the villains villains, the heroes heroes, the victims victims, and ourselves complicit. We can realize that all this talk about the fate of Earth has nothing to do with the planet’s tolerance for higher temperatures and everything to do with our species’ tolerance for self-delusion. And we can understand that when we speak about things like fuel-efficiency standards or gasoline taxes or methane flaring, we are speaking about nothing less than all we love and all we are.

Featured image by Fatima Moosa