On Tuesday afternoon, the queue to register for aid at Imizamo Yethu snaked all the way around the block to the BP on Main Road. Beyond the registration queue is an open piece of land, where packets and boxes of donated clothing have been set up for people to sort through.

The fire that blazed through Imizamo Yethu has left homes in ruin and families in crisis.

“Just after midnight, we heard people crying ‘Fire! Fire! Fire!’. The fire brigade did everything they could. There are no roads on the mountain, they couldn’t get in where they needed to,†said Enoch, a painter from Zimbabwe, who has lived in the settlement for over a year.

Enoch has an uncertain future. He had been living in a rented shack. It’s gone now, together with all his belongings, and he has yet to hear word from his landlord on what will happen next.

“We lost everything, all our papers, all our things.â€

The volunteers encouraged residents to choose what they needed, and I thought there was great dignity in that.

Women, seeing all the clothes and toiletries gathered as much as they could carry, were gently reminded by the volunteers, one shopping bag per person and to remember there were others who still needed. Surprisingly, they weren’t trying to get more clothing, but blankets and sanitary pads.

For many people, just getting clothing and blankets is a priority.

After the fire, Peter, who has lived in Imizamo Yethu for two-and-a-half years, is staying at a friend’s place, in a single room together with 14 other people who were displaced by the fire. “It’s very uncomfortable. We have nothing, nothing at all. We just collected some clothing and tonight we can change clothing,†he says.

“We can’t even build for ourselves because all the space is demarcated and people will attack us because they know we don’t own land. Our best hope is to find somewhere dry and warm to stay soon. We can’t even start thinking about work until we have a safe space.â€

Jarring realities

The residents clearly welcome the volunteers’ efforts but the jovial nature of the banter made me uncomfortable too. At the food tables, a volunteer says “Oopsie. Sir, you forgot your hotdog!†and laugh. It doesn’t seem mean-spirited. Rather, it seems the levity is a way to avoid feeling overwhelmed. But it was jarring.

It’s hard not to be floored by what you’re seeing at the camp. Moms with babies younger than three months, washing out porridge bowls with cold water, to make more porridge for the baby, because there’s nothing else to eat. Or the men’s dismayed faces, as if they can’t believe that this has happened to them. Walking almost trance-like in whichever direction they’re told.

A few men have had to be calmed down by the police, who, treating these people with care, instead of removing those who seem to be behaving erratically, have offered them the opportunity to gather themselves and try again. For the women, there was this look of determination that they weren’t leaving without a semblance of a plan. Food, clothing, shelter. They smile shyly and hope that this will usher in something better.

Tatenda stands across the road from the aid camp, eating rice from a styrofoam take away, which he shares with Enoch and Patrick. His meagre parcels are at his feet. As they wait for a friend to collect some clothing, he tells me doesn’t know how he will rebuild after this.

“We have been very safe here in Imizamo Yethu, we had a plan to save,†he says. But with everything he owns and everything he’s saved destroyed in the fire, Tatenda will have to start again from scratch.

“If you make R1 000 for the month, after food and transport and rent, we almost have nothing left,†he says. “All we want is to earn a living and look after our families. How are we supposed to do that?â€

Most people were hesitant to speak about what had happened and what their situation is right now. I got the impression that they were afraid it would jeopardise any help they would get.

Some of the women I spoke to told me it was great that they were able to get clothing and other necessary supplies but now they couldn’t leave their belongings without supervision, and they had to find someone to stay with their belongings at all times.

Not leaving

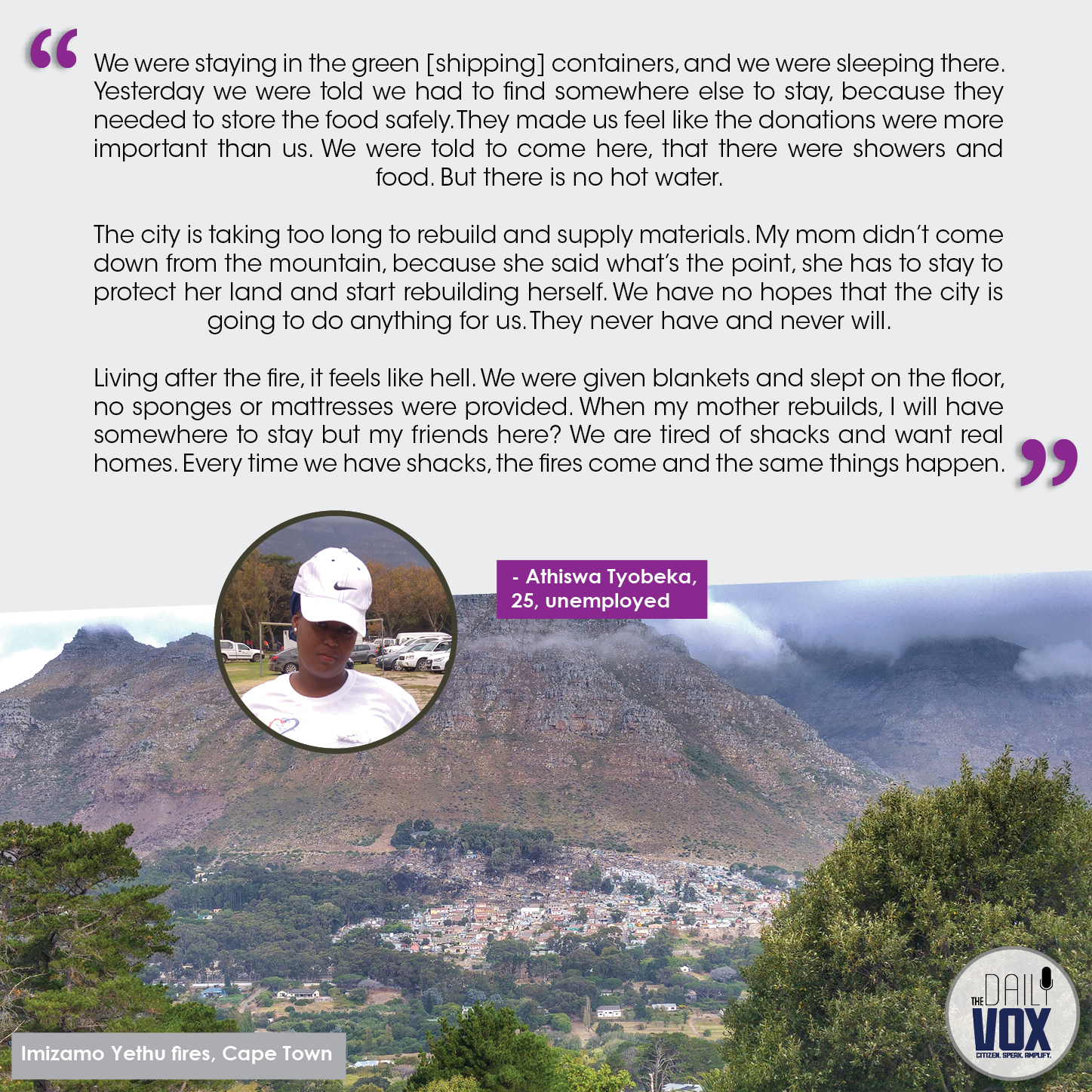

Other people, who had managed to rescue some of their belongings won’t leave their piece of land and wouldn’t come down from the mountainside to the donation point. Instead, they stayed up there with their belongings, afraid they might be stolen in their absence. They stood on whichever piece of land they’d staked out, hoping no one would claim it, and that they would get materials to begin rebuilding. Athiswa’s mother, for example, wouldn’t leave, saying there is nothing for her down there (at the donation areas). She has already organised some supplies and plans to rebuild on Thursday.

Firefighters stationed in the area, the Red Cross and other emergency services had been on hand all day, well past their shift times. The volunteers were on their second day, with some having been on site for over 18 hours.

Donations

A volunteer aid organisation started “six fires ago†called Thula Thula has been working in the area for the past three days. It’s tried to organise a starter pack with clothing, toiletries and a food parcel for everyone who’d been affected.

Vanessa*, a volunteer at Thula Thula, said that after the fire they kept waiting for the military intervention or some humanitarian group to turn up, but nothing materialised, so on Sunday they just started gathering donations. They spent all of Monday organising themselves and sorting through the clothing, food, toiletries, non-perishable goods and bedding that have been streaming in.

“The Hout Bay community really did come together to help the people of Imizamo Yethu,†Vanessa says.

The organisation has been running food banks, soup kitchens and clothing points at a few schools in Hout Bay. In Imizamo Yethu they’ve been taking people’s cell phone details and tallying the number of households that need help. They’ve registered over 2 000 people who represented about 10 000 people in their homes.

The system isn’t perfect. Some people were unable to register, or registered and didn’t receive a starter pack, but Vanessa says they’re doing the best they can.

And it’s true, the greater Hout Bay community has pulled together. At the entrance to Imizamo Yethu, I saw several white women in SUVs, offering people carrying parcels lifts into the township. Some looked afraid and apprehensive – both the drivers and the people taking the lifts. Both seemed so out of their element and still there they were. They showed up and did what they could, lifting heavy parcels and running to make sure everyone had a five-litre container of water with them before they left the donation point. These people, the victims, the volunteers, the civil servants floored me with their work ethic and dedication to helping.

*Name has been changed