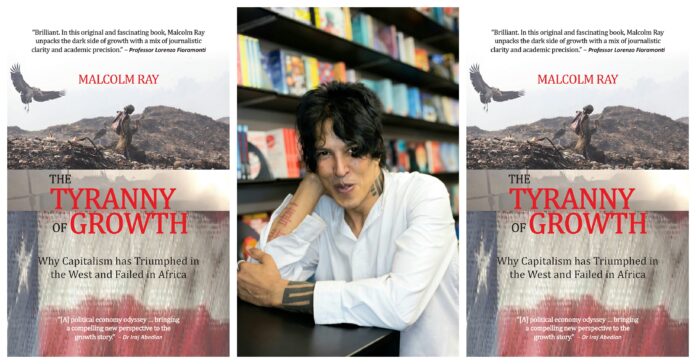

Professor Lorenzo Fioramonti has described Malcolm Ray’s book as a “original and fascinating account of the destruction, impoverishment and destitution caused by the obsession with economic growth ‘at all costs”. In Ray’s Tyranny of Growth, he explains how the official model used to calculate GDP data was designed to fit the growth myth. The Daily Vox spoke to Ray about his book.

READ MORE:

Extract: The Tyranny of Growth

*Interview has been edited for clarity and brevity.

How did you decide on (the title)?

The title was suggested to me by a combination of factors – both personal, and ideological/systemic. When the global financial meltdown of 2007 struck, it was clear to me that the problem did not reside in either regulatory or market failure. We were witnessing a systemic crisis of financialisation in a globalised economy, dominated by large institutional investors and banks in the West.

By the time the COVID-19 pandemic struck, I saw many of the shortcomings of the global economy, amplified by the unresolved issues thrown up by the 2007 crisis. By February 2021, roughly four million people had died. Many more were thrown into abject poverty. On the other side of the divide, large platform corporations were capitalising on opportunities to introduce products and services in the market created by the lockdowns. Many had doubled their net profits since the pandemic began. In other words, there was growth, just not for the poor and most vulnerable.

The word “tyranny” seemed apt in describing the growth regime that had come to dominate our lives.

How/when did you decide you wanted to write this book?

I decided to write the book in late February 2021 during one of the lockdowns. There was clearly greater awareness, driven by mass anxiety about the pandemic, among ordinary people about the limits of the economic system that governs our lives. I suspected that issues of climate change that had already become a global concern were converging, for the first time, with what people were starting to see as a humanitarian crisis during the pandemic. I was deeply unsatisfied with the public discourse in governments and within the media establishment on the economic impact of the pandemic. Lives were being lost because of inadequate healthcare. Livelihoods were imperiled because economic growth benefited elites.

By this time, I felt that tackling the concerns that the pandemic had amplified needed something more than an interpretation of the economic impact of the pandemic within the prevailing growth framework. It required a substantial reinterpretation of the growth doctrine itself and the neoclassical ideology that gave birth to it.

This was the point at which I decided on writing the book. I knew by this time that I had a solid thesis. Once I decided on the title, the narrative arc of the story formed in less than a day. I wanted to look at the distributional effects of capitalism in terms of GDP – the question of who gets what and why – from an African perspective. In dealing with this question, I wanted to rescue economics from the monopoly of economists and the false assertion that how we got here is a result of iron economic laws and not ideological and political choices by individuals and governments.

I knew that writing this story meant a process of historical layering, of getting to the core of an onion and then delayering it to figure out how it grew. I wanted to get to the weeds, to the players and agency behind the growth story, to understand the distributional effects of capitalism.

What is meant by a tyranny of growth?

What most people don’t know, and therefore accept as normal, is that GDP growth, in the sense in which we understand it today, is a recent economic goal and measure. It emerged in the United States during the Second World War in an attempt by the administration of President Franklin Roosevelt to justify the returns to the US economy of weapons manufacturing. The past 80-plus years since the formulation of GDP has shown us that nothing in the prevailing neoclassical growth paradigm makes the equitable redistribution of wealth arising from growth technically possible. The world today is on fire.

Capitalism, based on the growth at all costs doctrine, can’t be fixed. Governments were given a chance to stop the carnage. They have demonstrated that the pursuit of profit is a blind and mercenary endeavour.

The tyranny of growth is the social and environmental costs of the blind pursuit of profit.

It is a world in which we no longer produce goods and services to meet needs; we produce goods and services to make money for money’s sake. Growth is tyrannical because it is driven by a genocidal logic – a system designed to exclude from corporate balance sheets and national income estimates the social and environmental costs of what we call GDP.

Can you explain what the COVID-19 pandemic meant for the economic and social landscape in South Africa and the continent?

The economic impact of COVID had to be considered in terms of its differential social impact. On one level, COVID in SA as in other African economies has stalled trade and investment and hurt small businesses Much of what is occurring in South Africa and the continent appears to be following a global pattern of labour substitution – what has been called “the new normal”.

The new normal is nothing but a pretext by large corporates to legitimise a pre-existing malignant crisis of financialisation that magnified poverty and inequality during COVID by deploying larger ratios of technology to labour in order to cut production costs and boost returns to capital. In practical terms, poverty and informalism and resultant dependencies on social welfare nets are growing. In the near future we will see rising tax rates to pay down welfare costs, less disposable income, shrinking demand and stagflation.

How do you think the ideas and insights that emerge in your book can be practised in a practical way?

First, policy makers can start to shift policy discussions towards new measures of growth that are socially and ecologically literate. This is something that is both desirable and possible. It is a new lens through which to reimagine prosperity. It is a proposal toward a minimalist redefinition of growth that requires the inclusion of social and ecological metrics in our measure and calculation of growth. This can be complemented by similar sectoral efforts to come up with new metrics through the various sectoral associations that currently exist.

Second, the government can adjust the allocation of taxation toward incentives and disincentives that discourage social and ecological ruin and encourage socially impactful investments. Currently, corporate tax incentives in South Africa are heavily weighted toward the extractive mining sector, which is the biggest carbon emitter.

Third, and related to the above, grappling with a new growth metric and incentive systems can give us a basis to think not just about new metrics but new business models. In other words, we should be moving away from an obsession with saving toward social investments.

Lastly, individuals can play a role in moving the needle towards social and environmental literacy by developing a consciousness of self in how they exercise consumer power by becoming more discerning in what they consume.

What do you hope people take from your book and who should read it?

I hope that people will see more clearly that the growth doctrine we have come to accept as normal is an ideological construct that can be tamed and ultimately undone. My book offers a historical understanding of the economic system that governs our lives, in simple narrative form, and offers a new lens for people to re-imagine the world and how to change it. It is written for everyone, not just economists, students and policy makers. Insofar as economists and students would find the book compelling, it is written especially for the non-specialist.