uMlazi, the second-biggest township in the country, is where two Ethiopians suffered third-degree burns after about 30 people attacked them with petrol bombs during the start of the xenophobic attacks. Only one of them survived.

I had only ever been to uMlazi  once before. This week I returned to find out more about the threatening letters foreign shop owners had received,telling them to leave the area.

I was nervous about going to the area – I would be speaking to people about a sensitive topic and I didn’t want to be seen as taking either side. I decided to leave my phone behind, so I could roam around more freely knowing I wasn’t carrying anything anyone would want to steal. From the stories I’ve heard, xenophobic attacks aren’t the only crime one should be wary of at uMlazi.

My journey started at Vincent Supermarket, which a classmate had described to me as “the biggest foreign-owned supermarket in the townshipâ€.

The double-storey supermarket caught my eye while I was in the taxi, so I asked to jump off. I entered the building packed to capacity with stock and I could almost feel the stares I got from the people inside, singling me out as a stranger.

I asked a security guard where I could find the owner. He pointed me to a dark part of the store and I went there to find the nervous owner sitting behind a heavily fenced counter. I could only talk to the nervous owner through a small peephole used to exchange money with customers. Getting him to believe that I am a journalist and not an associate of the now notorious Mlazi Traders was a mission.

“How can I give you real information without a press card?†he repeatedly asked. The owner, who hailed from Somaliland, spoke English with a strong accent and this was sometimes a challenge, but what he did not fail to communicate was the distrust he had of me. He even refused to help me locate other foreign-owned shops.

Having visited the xenophobia victims’ camps in the past weeks and heard the experiences some foreigners had been through, I understood this man’s distrust and left his shop.

I wandered around the township and soon found a foreigner who runs a small spaza shop. He also couldn’t speak English very well but, although reluctant at first, he was willing to speak to me.

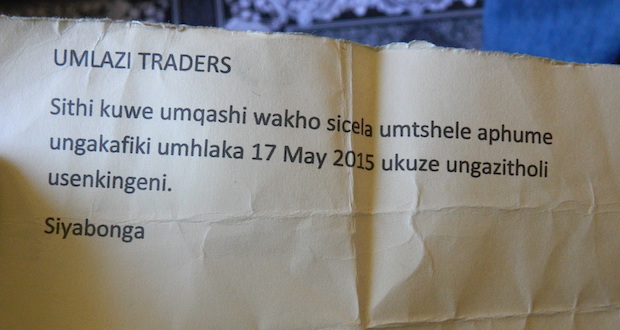

He told me how he, together with his brother who helps run the shop, received the letter telling them that they must be gone by the 17th of the month – giving them ten days to pack everything up and leave. The people who delivered the letters came in a convoy of more than 20 cars, causing traffic wherever they went and breeding panic. The cars would then park in the road and four or five men would get and deliver the letter by hand.

The shopkeeper seemed to relax when a local arrived, greeted us and had a brief, friendly conversation with him. The middle-aged man, whom I later found out was his landlord, clearly had a good relationship with the shop owner. I asked him to join our conversation and he revealed how four unknown men had come by his house late last week – a while after the shopkeeper he rents the shop space to had received his own letter. These men threatened him and left him with a very sketchy letter.

The letter to the landlord, written in Zulu, said: “We are saying to you please tell your tenant to leave before the 17th of May 2015 so that you don’t get into trouble. Thank you.†The men who brought the letter also threatened him verbally. They claimed to be representatives of Mlazi Traders, the subject heading of the letter also read Mlazi Traders. Apparently the landlord and his tenant had never heard of such an organisation until they received the letters

“I have built a very healthy relationship with this guy over the last two years; I can’t kick this guy out just like that now,†said the landlord. “I would rather fight them, than fight with my friend.â€

The landlord is unemployed and the rent from the shop owner is his main source of income.

He was the last person to tell me useful information that day. I went to more than 10 shops and no one else would speak to me. Some people thought I was a member of Mlazi Traders and was trying to get information from them. Those who did believed that I am a journalist did not want to talk for fear of angering the Mlazi Traders.

What I did gather was that – while fear and tension continue to escalate – the foreign shop owners still provide a needed service in the community. A struggle for turf may underlie much of the violence, but I’m still struggling to understand why local businessmen would want the foreigners out.