On Monday evening, ratings agency Standard & Poor’s downgraded South Africa’s sovereign credit rating to junk status. On Friday, a second ratings agency, Fitch, followed suit by downgrading SA’s foreign currency and local currency ratings. But what does is actually mean for the ordinary South African? The Daily Vox asked around.

For international investors, the credit rating is a measure of how safe or risky it is to lend money to or invest capital in a country. The downgrade tells investors that South Africa is a high credit risk for banks and international investors and that means we will be charged high interest rates on any international loans we receive.

Most articles I read online only mentioned the effects of this status on the middle class, and as an individual who grew up in a lower-class household in the Eastern Cape, I wondered what the downgrade meant for an ordinary working class South African. Do they understand what junk status is and how they will be affected by the downgrade?

I decided to ask an expert. Professor Haroon Bhorat, an economics lecturer at UCT, told me junk status basically means that the South African government would have less money to spend on social needs that the lower working class depend on, like housing, education and social grants.

“Effectively then, we have less expenditure available now to reduce poverty and inequality levels in the society. Government is now poorer and individuals who are employed in the public sector will no doubt have to face lower real wages, assuming government does not try to further debt-finance higher salaries,” he said. Bhorat also said the effect of the downgrade on employment would be sharply felt.

Afterwards, I headed to the streets of Johannesburg to find out what ordinary people made of the downgrade.

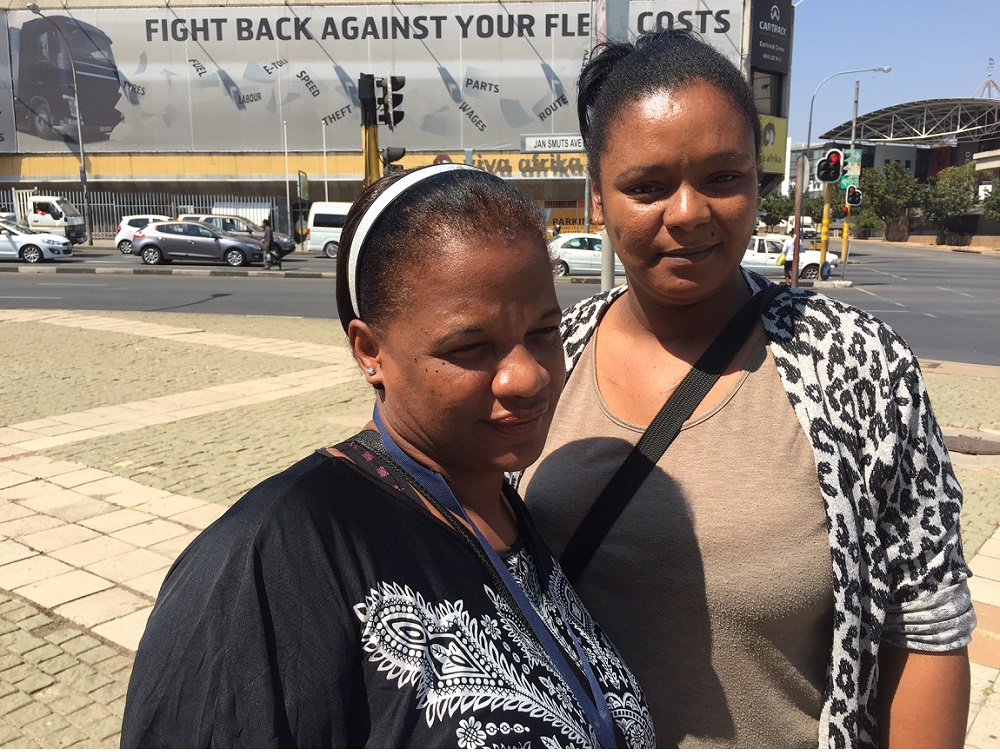

Brenda Jansen (33) and Geordia Ficks (33), were standing in front of a building at the corner of Jan Smuts Avenue carrying flip files. They told me they were unemployed and didn’t know anything about the downgrade.

Even those who were employed raised their concerns about possible retrenchments because of the downgrade, and the effect this might have on families. I found Glenda Shikwamba (22), who works for a consulting company, queuing for lunch nearby. Glenda said she was devastated by news of the credit downgrade.

Brian Shabangu (27), a bank clerk, shared her frustrations. Shabangu said President Jacob Zuma should be held accountable for any effect on youth employment.

Keshia Munsamy, 28, said the downgrade is bad for everyone because it puts borrowers in a bad position.

Munsamy said she believes citizens need to call for the restructuring of South Africa’s political economy. “Those who are corrupting the country, are hiding behind the political faces we see in the media,” she said.

Most of us don’t really understand how a credit rating will affect our lives – and there’s no way to predict its effect with any certainty. But the idea that the jobs market may get even worse or that household costs could rise more steeply, is scary to contemplate.

Additional reporting by Alinaswe Lusengo