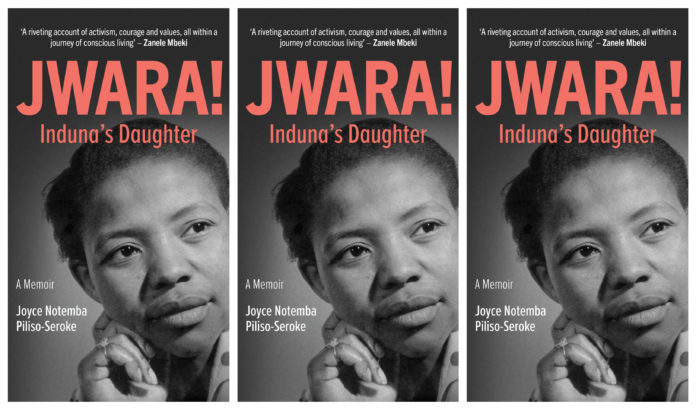

Born into privilege, Joyce PilisoSeroke questioned her environment. She grew up in a gated compound for the mining elite at Crown Mines but soon became aware of the harshness of the lives of the men in the barracks behind the fence.

Driven by an inner calling, Joyce was determined to change lives and become a social worker. At Fort Hare she studied under ZK Matthews and qualified at Swansea University in the UK. Back home she taught at Orlando High School. Politically active, she was detained as the 1976 revolt rocked South Africa. From here, her journey became increasingly political.

Piliso-Seroke championed women’s and human rights as vice-president of the World YWCA, serving on the TRC and chair of the Gender Commission. Yet, as her colourful autobiography reveals, her long life is filled also with jazz, travel, her beloved ‘stokkie’ and her unshakeable faith. Mama Joyce’s story is also the story of the tumultuous last century in South Africa.

Childhood adventures. Life as a laat lammetjie. [EXTRACT BELOW]

As the baby of the family, born when my father was already 70 years old – a laat lammetjie – I was his pet. I remember that every time when he came home from work, he always called out from the gate, ‘Nanoo, nanoo, little one.’ I would rush out excitedly to meet him, and he would swing me high in the air.

While growing up, I was a handful and adventurous, and my father always encouraged me to explore. I remember that when I was seven years old, I secretly ventured out to visit my sister Miriam in Orlando East, the first location f or Africans after they had been forcefully removed from Doornfontein and Prospect Township in Johannesburg. I had some cash for sweets that I had saved from my father’s constant gifts and walked to Mayfair Station, where I boarded the train to Orlando Station, armed with my sister’s address.

When I arrived, I asked an elderly woman for directions to 830/831 Orlando. When she realised that I was unaccompanied, she decided to take me there, and I arrived hungry and tired. Imagine my sister and her husband’s shock to see me appear out of nowhere. They were having their lunch, and I was suddenly seized by pangs of hunger. Instead of offering me food, they bundled me into their car and headed home to Crown Mines. I became aware of the gravity of the situation, and along the way back, I started whimpering, dreading the severe punishment I was sure was awaiting me.

My parents had been frantic after being told by Biza that I could not be found anywhere. My uncle M. D. was visiting from 14 Shaft. As he was a strict disciplinarian, he expected me to be punished, and he suggested to my father that I should be spanked: ‘Kats’ umntwana sibari, kats’ umntwana sibari (give this child a beating),’ and he said it with such vehemence that it seemed that he was dying to execute the punishment himself. I burst out crying, sincerely regretting my earlier impulse of going to visit my sister. Uncle M. D. was very disappointed and annoyed when my father took me into his arms and bragged that I was a bright and brave child to have ventured alone to Orlando at such a tender age, and he rewarded me with sweets. He nevertheless cautioned me and explained the dangers of travelling alone via public transport and told me that I had caused them a great deal of anxiety and made me promise never to do that again.

My home, the nduna’s residence, was detached from Mavumbuka and was much bigger than the average houses of the married quarters. Adjacent to it was the guest house, which catered for traditional chiefs and their councillors who, from time to time, visited their subjects working at the mines. My home was separated from the guest house by a row of tall blue gum trees. Hence, it was possible to maintain some privacy when the guest house was occupied by the visiting chiefs. Our stoep was shiny red and was my father’s favourite place to relax in his wingback chair in the afternoon after work. His chair was strategically placed to enable him to observe the residents as they passed in and out of Mavumbuka. Most of the men who passed by paused to wave at him, calling out, ‘Jwara.’ Others advanced to our gate to greet him or chat with him.

The front door at the top of the stoep led to the entrance hall, which had a mirrored stand with hooks on which guests could hang their coats, hats and umbrellas. My father’s bowler hat, worn only on special occasions, was always conspicuously perched on top of the stand. The sitting room was the next room, and it was simply furnished with a Chesterfield suite. The old-fashioned radiogram in one corner was only switched on for the news, the weather report and church services. Darbie played his 78 RPM records only when my father was away. In winter, it was only my parents, relatives and visitors who occupied the sitting room to enjoy the glowing coals of the fireplace; we children had to remain in the kitchen. Our dining room had a very long table and was the centre of entertainment when we had visitors. The younger girls took turns serving the meals, and we had to be sharp and prompt when my mother rang the bell. She did not tolerate any sloppiness and would always admonish us, ‘Khawuleza mntwanandini (hurry up, child).’

My father was a generous host who always bragged about my mother’s cuisine, persuading his guests to take second helpings. We children did not sit at the table with the older folk. We had our meals served in the kitchen. There, the others played a game making bets for our parents’ leftover meat. In spite of knowing that they would get their food after the best parts were given to older members of the family and visitors, they played anyway.

Much to the annoyance of the other children, I did not have to join in. My father always called me to the dining room to receive the piece of meat he had reserved for me. I remember one night that a young girl, uNozizwe, who had been visiting from Transkei, was frustrated because she never was lucky to pick a plate. To our embarrassment, she called out loudly from the kitchen, ‘Ithambo lomntu wasemzini lelam (I pick the visitor’s piece of meat).’ My mother was livid, for everyone in the dining room could hear Nozizwe’s loud plea. She was walloped by my mother, who from that day decided that in the future, we would be served at the same time as them and the kitchen door would be closed during mealtimes.

Our kitchen was always warm because we used a coal stove for cooking. Although the mine supplied us with electricity, we only started using electrical appliances in the kitchen much later in the 1950s. The kitchen also served as a study room for us children, and we spread our books on the well-scrubbed tabletop every night after supper to do our homework with strict supervision from my mother. Some of the boys slept on the floor in that warm room, and we envied them on the cold winter nights. There were four bedrooms: one for my parents, one for my aunts, one for the boys and another for the girls. There was no particular guest room, so we were made to vacate our rooms for the benefit of visitors. The bathroom had an old tub with running cold water. As there was no geyser, we had to heat the water in large pots on the coal stove before the older people and visitors could have their bath. That was the boys’ job, as they could lift the heavy pots.

My mother was a keen gardener, and our garden was the envy of Mavumbuka. Her favourite flowers w ere gladioli, carnations and roses. Gypsy, her pet dog, always kept us on our toes, as he barked and played and dug holes in the garden, much to my mother’s annoyance. When Gypsy was hit by a car, my mother was so sad that she cried unabashedly and vowed that she would never replace him. Instead, she kept four cats: Ginger, Scratch, Mpofu and Tozi. Whenever she left home to attend a YWCA conference or church committee meeting, she always sent a telegram with the standard message: ‘Arrived safely. Don’t forget to feed the cats and water the garden.’ Telegrams were the quickest way of sending messages, as we did not have a telephone.

Because of the number of visitors who came to Johannesburg from all corners of the country on business trips or for holidays, and because no hotels at the time were open to Blacks, our home accommodated people from all walks of life: relatives, friends and strangers. As a result, we children had to give up our beds most of the time and sometimes wake up in the small hours of the morning to make room for visitors who had arrived after travelling by train. But the moment our guests departed, you should have seen us jump on our beds to enjoy the fleeting comfort … knowing too well that very soon we would have to vacate our rooms again.

Published by Tafelberg, the book is available online and at all good bookstores.