On Tuesday the Socio-Economic Rights Institute of South Africa (Seri) released a legal and practical guide to student protests. It is a user-friendly guide for students to better understand their rights when engaging in protests, the procedures of law and how to protect themselves when undertaking disruptive activism. It draws inspiration primarily from the experiences of student protests since 2015 and is a useful toolkit for student protesters. The Daily Vox looks at how the document answers five legal questions that come up during student protests.

1. A protest is meant to be disruptive, but how disruptive can it be before it is no longer constitutionally protected?

The Constitution is the supreme law of the country, and it protects the right to protest as long as the protest is peaceful and unarmed. Peaceful in this context means that it the protest does not involve physical harm – and sometimes even threat of it – to people or property. So harm to people or burning, destroying or vandalising public or private property is not allowed. But Seri points out that the fact that certain individuals within a protest may take part in the destruction of property, for example, does not mean the entire protest is illegal. The protesters who are uninvolved in violent acts remain protected by the Constitution.

“The Constitutional Court has said that a protest cannot simply be considered violent because some protesters are involved in sporadic violent acts or criminal activities. In other words, if you take part in a protest during which some of the other protesters commit violent acts, this will not mean that your own actions will be considered violent,†the guide says.

In terms of disruption, the interruption of “business as usual†is often the very point of protest, and this is protected. Seri uses examples of disrupting lectures, blocking entrances to universities and occupying buildings as examples. In each case, there’s a degree of ambiguity involving the context. For example, interrupting a lecture for five minutes may be short enough to ensure that the disruption is short enough to be protected by the Constitution; occupations will always be protected but only as long as people are still allowed to go about their jobs; and blocking entrances to campuses could be argued for if there are alternative ways to access the premises.

2. Do all protests have to be planned and what makes them lawful?

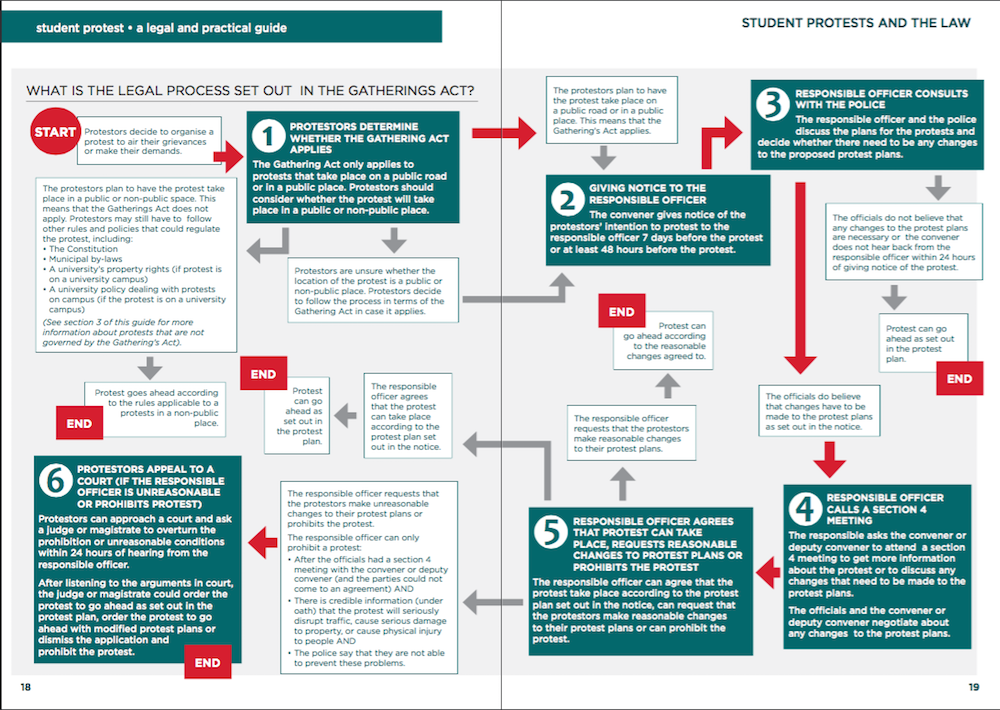

The Regulation of Gatherings Act is a law that helps govern protests within South Africa by outlining the procedures through which protests are lawful – and thus legally protected by the police. The Act applies under two conditions, the protest must take place in a public space and it must include 15 people or more – less than this is not considered a protest. If the Act is found to apply there is a process that must be followed for a protest to be authorised by city officials and the South African Police Service (SAPS). If the process is followed and the protest is both peaceful and unarmed, the protest is lawful and legally protected.

An exception to the Act’s requirement of giving advanced notice are in cases of “spontaneous protestâ€. As Seri points out, the law protects instances where a protest occurs organically without prior planning involved. But it is important to note that arguments for spontaneity almost always never come up in court as a consideration for arrests that have already taken place. Even then, providing evidence of spontaneity can be challenging – emails and WhatsApp messages indicating that the protest was not planned in advance would be useful in such cases.

3. How do you know when an interdict against a protest is unfair or infringes on your Constitutional rights?

An interdict is a court order that prohibits a person or group of people from doing something – essentially it makes it unlawful for them to do whatever is prohibited in the interdict. Universities have a legal right to apply for interdicts prohibiting specific students from taking part in clearly defined unlawful or criminal acts, but, as Seri notes, in the last few years, universities have often abused this process by getting overly-broad interdicts that try to prevent students from taking part in any type of protest. The publication cites examples where the Supreme Court of Appeal overturned interdicts that were initially granted by to universities.

Seri advises that there are usually two ways interdicts are used unlawfully: when what is interdicted is too broad and when unnamed and difficult-to-identify groups are interdicted. Overly broad interdicts are vague and prohibit students from participating in a wide range of activities that go beyond what is required to ensure the university’s rights are protected. The courts are not allowed to prohibit students from doing things which do not threaten or harm the university, especially where students rights are involved.

“Students can therefore only be interdicted from taking part in specific, clearly-defined, unlawful acts or criminal activity,†the document says.

A university can also only obtain an interdict against a specific person or group of people that are expressly named or are easily identified. Courts are not empowered to grant interdicts against the general public or large groups of people who are not named or clearly identified ordering them to obey the law, as it is unclear who the interdict is to be applied to and who ascertains that.

Seri says that such interdicts are “overly broad and unlawful, and can be set aside on appeal (be undone by a court)â€.

4. What rules do police and private security need to follow when engaging with protesters?

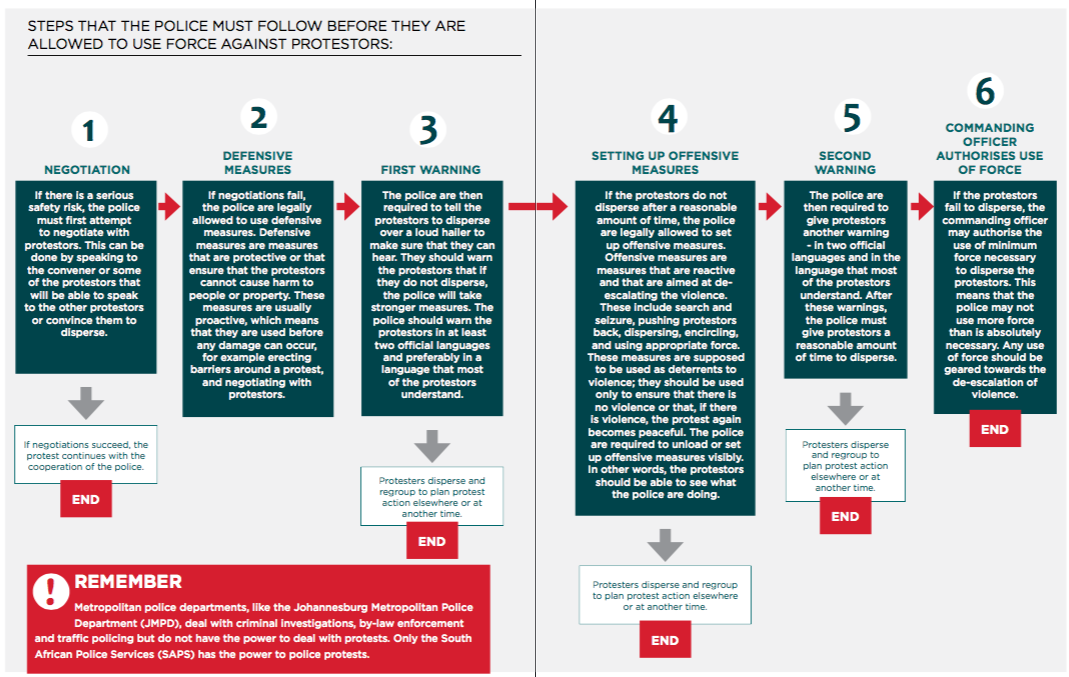

Seri says the police are legally bound to protect and create a safe space for protesters to air their issues, even spontaneous protesters. This is obviously rarely the case, but the official SAPS guidelines (SAPS National Instruction) indicates that the police are required to negotiate with protesters on an ongoing basis and try to resolve any issues that arise between the them and protesters in peaceful ways before any violence occurs.

“The National Instruction clearly says that ‘the use of force must be avoided at all costs’ and that the police ‘must display the highest degree of tolerance,’†the guide says.

The police are only allowed to use force on protesters if there are reasonable grounds to believe it is necessary to prevent injury, death or damage to property. But it is to be a last measure only used once all other possible options have been tried. Even then, the use of force needs to be proportional to the threat posed by protesters. The law even sets out steps that must be followed before the use of force is warranted.

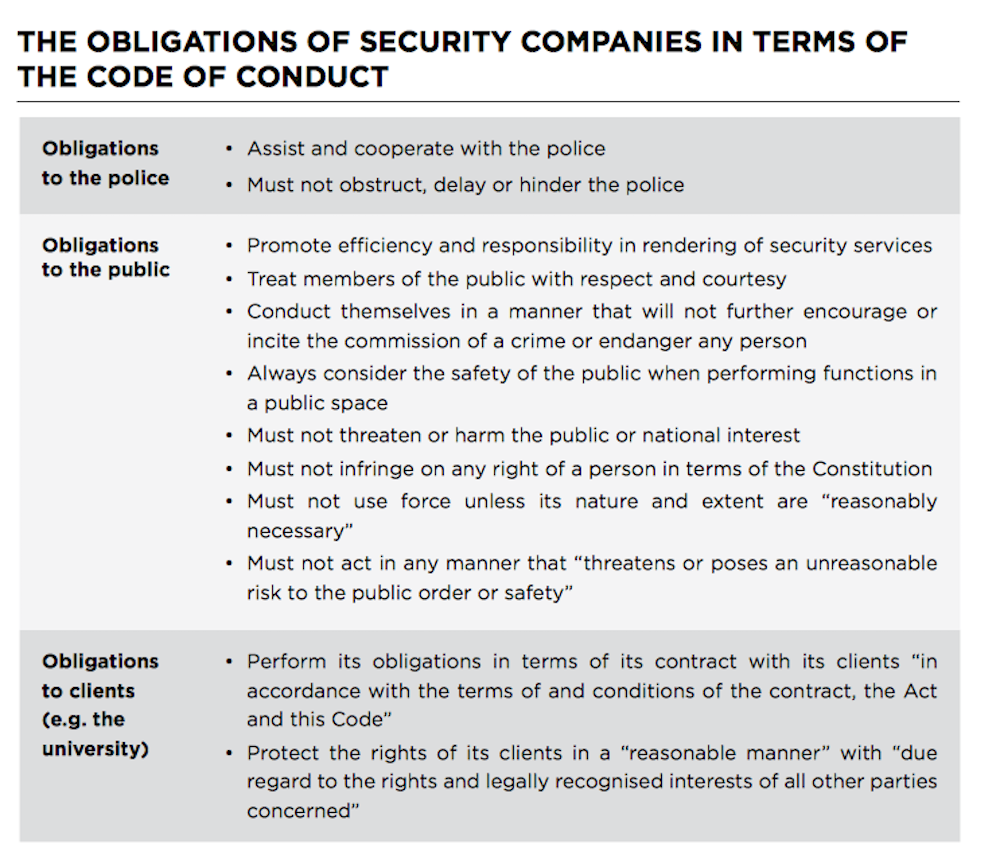

Private security guards are a common feature at many universities across SA, but don’t have any special powers to enforce the law that police do. At most they can perform a “citizen’s arrest†like any other person. Security guards are ultimately accountable to the university itself as their client. However, beyond the Constitution, security guards are bound by the Private Security Industry Regulation Act. The law says that security guards must adhere to a specific code of conduct for security service providers. Be sure to check if the guards on your campus adhere to it.

“Security guards who commit go against the Code are, in addition to the consequences for the security companies they work for, guilty of a criminal offence which is punishable by up to 2 years in prison or a fine or both,†the guide says.

5. What do I do if I’m arrested?

It’s not uncommon that the police arrest students for protest action – legal or otherwise. Police are allowed to arrest protesters without a warrant of arrest if they see the protester committing a crime or have probable cause to believe that the protester was involved in committing a crime. An arresting officer must follow the Criminal Procedure Act. This Act states that an officer must inform the protester that the arrest is taking place, tell them why it is taking place and have physical control of the protester when the arrest happens. If any of these three requirements does not happen, the arrest may be unlawful. It is often the case that student protesters are arrested without being informed of the reason.

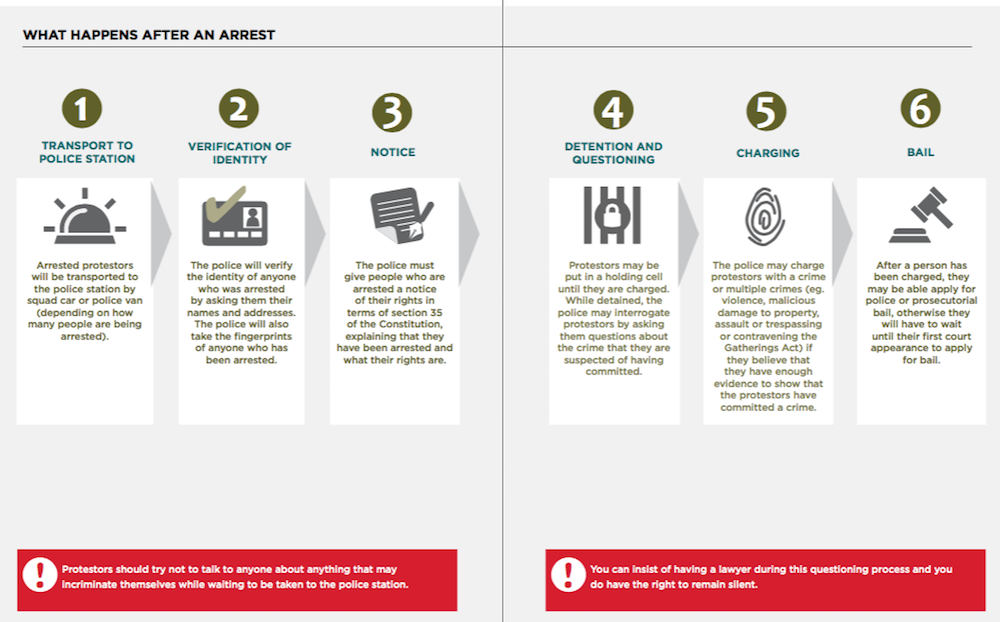

Once arrested it is handy to remember that you have the right to remain silent and the right to legal representation – the latter of which the government must pay for if you cannot afford it. Arrests should follow the procedure below.