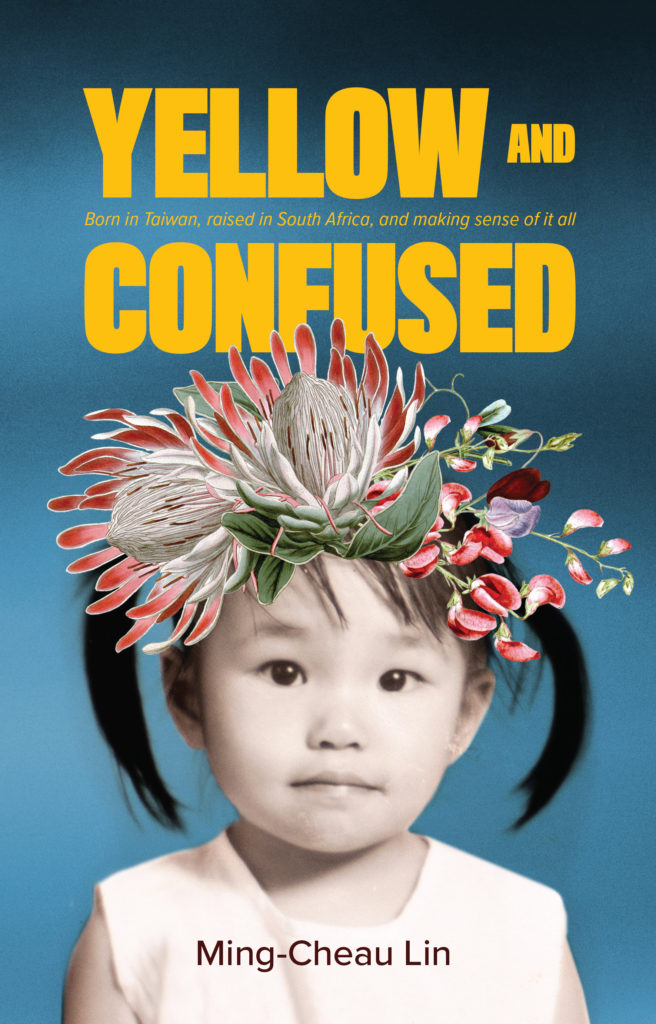

Yellow And Confused is the latest release from cookbook author, blogger and storyteller Ming-Cheau Lin. It is a deeply personal and in-depth look into her life as a third culture immigrant in South Africa. In 2018 Lin released her cookbook Just Add Rice. The book focused on Taiwanese food interspersed with stories from Lin’s childhood and growing up. She takes the conversations started in the cookbook and delves deeper into them in Yellow and Confused.

Yellow and Confused sums up Lin’s life journey in the book.

Yellow is the term used to refer to East Asians in a derogatory manner. Initially the colonisers referred to Chinese and other east Asian people as people as white as a race descriptor. However, Michael Keevak, author of ‘Becoming Yellow: A Short History of Racial Thinking says that when it became clear that Chinese and Japanese were unwilling to participate in European systems, they began to darken in published texts. They were referred to as yellow. This racist term has persisted to modern times as a way to refer to East Asian people.

Like most colonised people, East Asian people including Taiwanese people had their identities influenced by whiteness. However, to complicate things for Lin, her family moved to South Africa. Bloemfontein more specifically during apartheid. That’s why Lin speaks of something called third culture immigrant.

In a previous interview with The Daily Vox, Lin said: “Basically a third culture child is when your foundation culture is different from the society around you. I am a first-generation immigrant – even though I have no memories from Taiwan – my home culture is Taiwanese. Being in South Africa even though it’s a black country, the dominant culture is Western society.”

This leads to confusion.

Yellow and Confused is a beautiful but difficult read at times. Lin cuts to the heart of many issues facing non-black people of colour living in South Africa. She recounts her experiences of being at the receiving end of racism and sexual harassment based on her identity as a Taiwanese-South African immigrant.

However, she also touches on the issues facing her community. This includes racism, classism, homophobia and colourism from the Taiwanese community. As a South African woman of Indian ancestry, this felt so familiar and uncomfortable. When Lin speaks about the problematic nature of her community, she could be speaking about my community. This made the book extremely interesting as I could relate to a lot of what she was speaking about. Belonging to the Asian community means facing discrimination from whiteness. It also means having to deal with a community that has internalised many problematic behaviours through assimilation.

Lin takes the reader through her process of unlearning and learning the harmful and toxic behaviour she internalised as a child. There are definitely parts when reading these parts that makes one stop. To go on reading at that point would be too difficult. This includes parts when Lin recounts how she was bullied as a child for bringing Taiwanese food to school. The reactions of the children even at the age are so hurtful. Lin manages to convey the pain and hurt she is feeling so vividly.

From school friendships to romantic relationships and family relations, Lin lays it all bare. There is no area which she does not venture it. It’s the raw honesty of the book that’s refreshing. Lin is not afraid to call out her own problematic behaviour. She admits to her past faults as well as those of the people around her.

The book is an easy read though because Lin has an interesting writing style. It feels like you are sitting and having a conversation with her over coffee and listening to her story. This makes the book accessible even when she is dealing with heavy matters. At times it even reads like a fiction book. However, Lin also makes fascinating observations to bring together all her stories with a lesson she learned.

Lin ends of the book by saying: “What I have come to understand is that being Asian is Africa us multi-layered, identity is a plural.” She is likely why she included at the end of the book several short voxes from other second and third East Asian immigrants. This includes people from Burma, China, Japan, and South Korea. The people recount their struggles and realisations of their identity as Asians living in South Africa.

Asians might make up less than 3% of the South Africa population. East Asians are an even smaller number. However, as South Africa grapples with so many issues related to identity including racism, xenophobia, and inequality to name a few, this book is sure to make its mark.

If nothing less this book is a great sign of diversifying South Africa literature market. For too long the market has been dominated by certain kinds of voices. Yellow and Confused joins the ranks of diverse voices telling their stories. We can’t wait for more Asian people to be inspired by Lin and write their own stories.

Yellow and Confused is published by Kwela Books and available at all great bookstores and online.

Featured image by Fatima Moosa