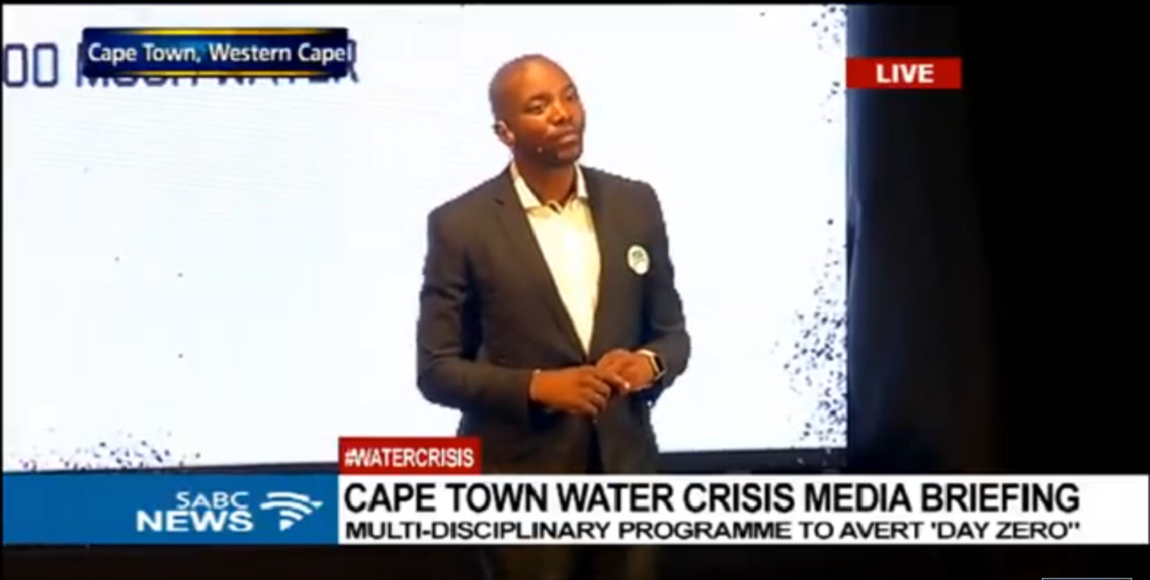

On Wednesday, the leader of the Democratic Alliance (DA) Mmusi Maimane hosted a press conference on the City of Cape Town’s looming water crisis. Flanked by city and provincial officials, he announced that he was ‘taking political control’ of the local and provincial governments’ response to the crisis. However, is he constitutionally mandated to do so? Or has he stepped over the line?

“As leader of the DA, all DA governments are accountable to me through the federal executive. I am not fully satisfied with the way the city has responded to the drought crisis, its communication, in particular, has fallen short,†Maimane said at the beginning of his presentation.

“This lack of clarity is not what citizens should expect from any DA government. It’s time for decisive action. And today I want to share some of the decisive action I have taken. Firstly, I have taken the unprecedented step of taking political control of our respective government’s responses to the situation,†he said.

To be clear, ‘political control’ of the Cape Town and Western Cape response to the drought is now led by Maimane, who in government is just an ordinary member of parliament and otherwise has no constitutionally mandated local or provincial role. In a communique sent to DA public representatives in Cape Town on Tuesday, Maimane said, “I will be taking the unprecedented step of taking personal control of how our governments respond to this crisis…â€

This control, it emerged from the conference, was the appointment of a Defeat Day Zero Team, comprising of Maimane, the Western Cape premier Helen Zille, the City of Cape Town deputy mayor Ian Neilson, the mayoral committee member for informal settlements, water and waste services and energy Xanthea Limberg, the Western Cape MEC for local government, environmental affairs and development planning Anton Bredell, and Bonginkosi Madikizela, the DA leader for the Western Cape. The City of Cape Town mayor Patricia de Lille was conspicuously absent.

Also take note of this statement from DA Leader Mmusi Maimane, in an “unprecedented move” he is taking personal control of the #CPTWaterCrisis #DayZero pic.twitter.com/DJEcTueHyO

— Aarti Narsee (@ajnarsee) January 24, 2018

How quickly things change…

Nine years seems like an aeon in South African politics, but it was just nine years ago that the then president of the republic, Kgalema Motlanthe, put to death the Directorate of Special Operations (the Scorpions), a unit in the National Prosecuting Authority. A year before, the African National Congress had resolved to disband the unit at its 52nd national conference in Polokwane – where it also for the first time elected Jacob Zuma to lead it.

The reaction to the end of the Scorpions was volcanic – no less so than from Zille, at the time the leader of the DA. She wrote : “The dissolution of the Scorpions is the logical outcome of the ANC’s model of closed, crony politics in which the interests of the party trump the rights of citizens and the higher law of the party means independent institutions must be undermined or taken over if they thwart the abuse of power by the ANC’s ruling clique.â€

Unconstitutional conflation of position of party leader with state (province and city) responsibility. https://t.co/4ZcNZk5CGu

— Pierre de Vos (@pierredevos) January 24, 2018

Zille further lamented what she said was the “the boundary between party and state†in certain deployments at national, provincial and local governments, including the appointment of Mike Sutcliffe as the city manager of Durban.

This line of attack was repeated in the UK’s Telegraph newspaper in the run-up to the 2009 national elections: “… the distinction between the party and state becomes ever more blurred, with the ANC quietly taking control of supposedly independent institutions, notably the national prosecuting authority, and turning them into tools for political struggle.â€

In 2016, the Public Protector found that the Free State provincial government had been conflating state and party by using a government food distribution programme to openly campaign for the ANC in the run-up to the 2011 local government elections. In response, Roy Jankielsohn, the leader of the DA in the Free State, said, “the DA has long maintained that the line between party and state in the province has been conflated and the public protector’s finding supports this view.â€

The line between state and party has been a DA attack against the ANC for the longest time – since the days when ‘cadre deployment’ made for substantive debate on national television and the opinion pages.

Crises have a way of upending these things. Day Zero looms upon Cape Town as the water levels that feed into the city reach critically low levels, meaning that taps in most residential areas will be turned off. Residents will have to queue for an allocated amount of water every day, at 200 collection points throughout the city. It’s a ghastly scenario – one which has not as yet prompted all the residents to minimise water usage to the required levels.

In the midst of this looming crisis, the government of Cape Town has been taken up by another political crisis – one involving the Cape Town mayor Patricia de Lille. As head of the city government, under the ordinary run of things, she would have been front-and-centre of the city government’s crisis communications efforts. She is not, though. Amidst accusations of irregularities and corruption, that task was passed on to her deputy Ian Neilson last week by the city council.

On Monday, Zille published a column in Daily Maverick, saying that in spite of the strict interpretation of the separation of powers principle, the provincial government was stepping up its interventions.

She wrote: “The principle (that each sphere of government must respect the integrity, mandate and functions of other spheres) is entrenched in our Constitution. Court judgments have been consistent: a sphere of government trying to interfere with the mandate of another has always been pushed back. Even a “mandamus†obliging the national department of water and sanitation to provide bulk water supplies would have to be sought by the City, not the province. Last week, I still accepted these stringent limits on the province’s capacity to intervene. No longer.â€

Maimane’s political intervention therefore represents the third change that has been made in the drought disaster management. The messaging has also changed – from De Lille’s fatalist “Day Zero is almost inevitable†to Maimane’s “Yes we can defeat Day Zeroâ€. Zille’s main contribution on Wednesday was to attempt to redirect blame to the national government, specifically the ministry of water and sanitation. Time will tell whether the minister Nomvula Mokonyane will be compelled to accept her portion of the blame – which is almost all of it, according to the premier. I suspect though that people will more immediately blame the local government once the reality of daily rationing kicks in after Day Zero.

We’ve reached a point of no return. 60% of Capetonians are callously using more than 87litres per day. Day Zero is now likely.Punitive tariff to force high users to reduce demand. 50litres per person per day for the next 150 days – Drought Charge likely to be scrapped by Council. pic.twitter.com/pmsn06U9Iy

— Patricia de Lille (@PatriciaDeLille) January 18, 2018

That there has been a tremendous failure in the city government – particularly of crisis communications – is vastly evident. (One wonders: amidst the litany of bad information floating around, what exactly is Tony Leon’s Resolve Communications being paid to do?) Zille’s column on Monday was a great first step towards clear crisis communications.

Maimane’s intervention could have been led by Zille, as a constitutionally mandated leader of the provincial government, with oversight powers over the municipality. Neilson, as the newly-appointed municipal disaster preparation leader, would have rightly been a part of the team. Why it was necessary for the leader of a political party to rush in and take over may perhaps be made clear some time down the line, when somehow, this is all behind us. But on Wednesday, what we saw was the blurring of lines between party and state in Cape Town and the Western Cape.

Featured image via Facebook Live