Salim Vally reflects on the Soweto Uprising and those who lost their lives.

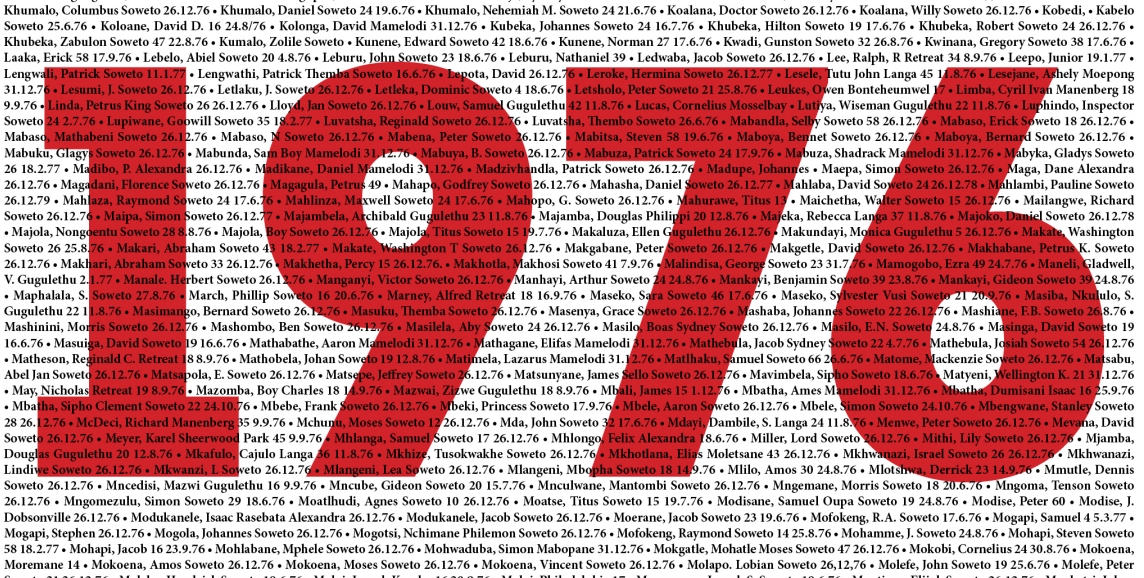

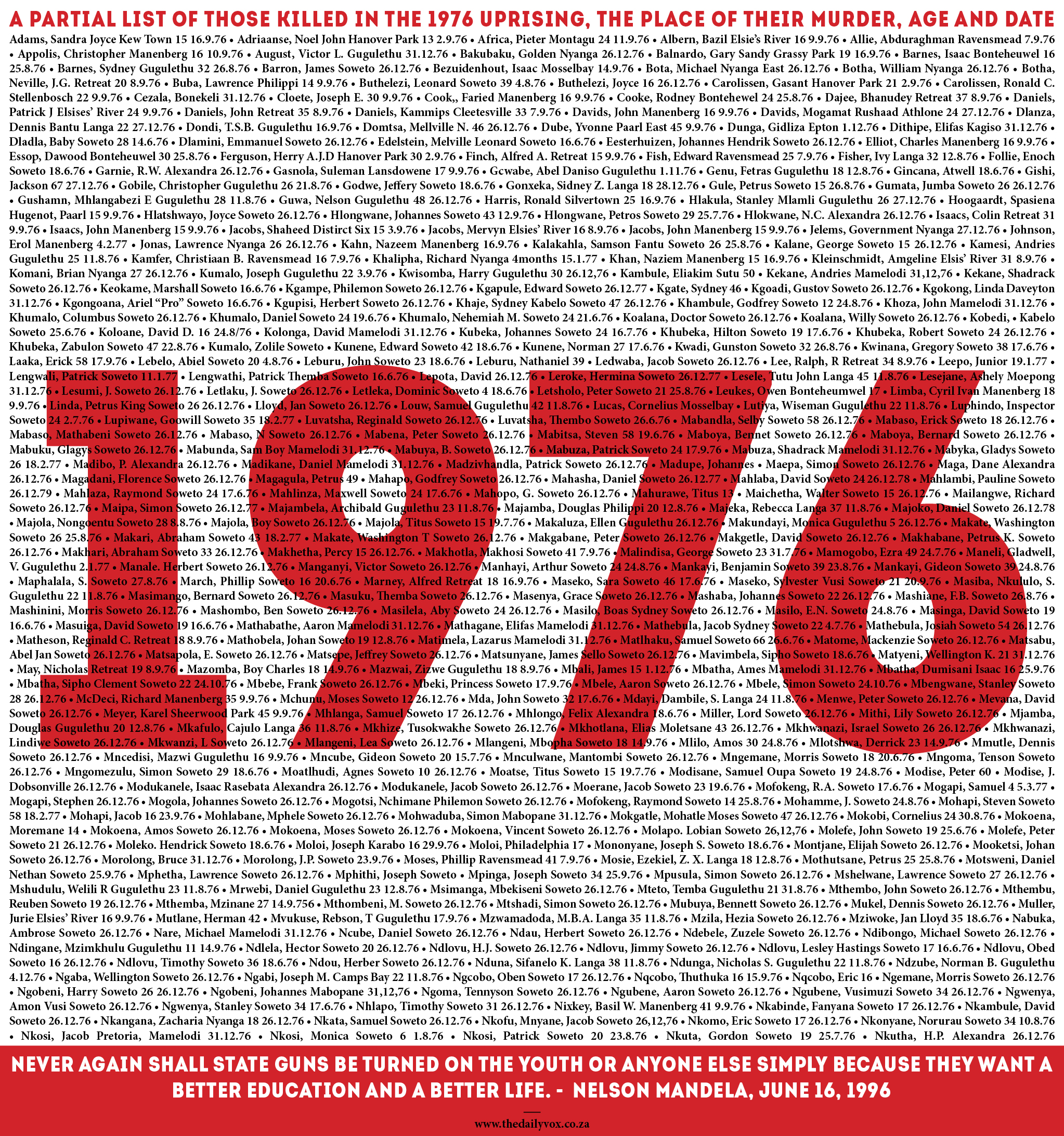

A partial list of the martyrs of the 1976 Uprising, the place of their murder, age and date below (list courtesy of SA History online).

Writing with dignity and suppressed rage shortly after the Uprising where about 800 people, largely children and youth were shot by the apartheid state’s police and those they directed, Mazizi Kunene was resolute:

‘We have entered the night to tell our tale

To listen to those who have not spoken

We, who have seen our children die in the morning,

Deserve to be listened to

Nothing really matters except the grief of our children.

Their tears must be revered, their inner silence

Speaks louder than the spoken words; and all being

And all life shouts out in outrage…

There is nothing more we can fear.’

In a seminal speech on the 10th anniversary of the Uprising, Neville Alexander presciently indicated that, “In the seamless web of South African history, the 16th of June 1976 represents both an end and a beginning – the rifles and ammunition that laid low Hector Peterson and his comrades and that sent the Tsietsi Mashininis into exile and the Dan Motsisis into prison,” put an end to illusions that the struggle for educational equality could be separated from the struggle for democracy and “eventually from class emancipation.”

Sibongile Mkhabela (nee Mthembu) from a courageous and selfless leadership collective – members of the South African Students’ Movement (SASM) the high school wing of the Black Consciousness Movement – who mobilised an estimated 10 000 students that began the march early on a cold Highveld winter morning in Soweto on June 16th.

She recalled: “As we led the big march our spirits lifted and the songs began to be more spontaneous and full of vitality: Sizobadubula ngembhay’mbhayi, a song by Miriam Makeba, was among the most popular freedom songs on that morning, but we also made up songs as we marched.”

During that march and in the ensuing weeks after, the initial joy and laughter of young people was transformed into cries of anguish and pain as the students were massacred in the dusty streets not only of Soweto but as can be seen from the list below in many other parts of the country. And tortured in the many prisons of our country. Despite the regime’s strategy of dividing the oppressed through the Bantustan policy, the Group Areas Act, and even separating, for instance, sections of Soweto into ‘Zulu’ and ‘Sotho’ areas there was a determined attempt at unity and the slogan ‘One Azania, One Nation’ baptised in blood, resonated and in the context of the times, was revolutionary. Look at the names of the young people and where they were killed: Soweto, Manenberg, Elsies River, Mamelodi, Alexandra, Gugulethu, Mosselbay, Athlone. In contrast to the crassness today we did not see ourselves through the apartheid categories imposed on us. We were not ‘minorities’ or ‘Zulu’, ‘Coloured’, ‘Indian’ or ‘Xhosa.’

We remember those who made the ultimate sacrifice and the best way to memorialise them is not through statues, false promises and rhetoric but to build a better country than what we have today.

The views expressed by this author do not necessarily reflect The Daily Vox’s editorial policy.