Through his recollections of Ramadans past, ADLI JACOBS reflects on growing older in the tumult of South Africa.

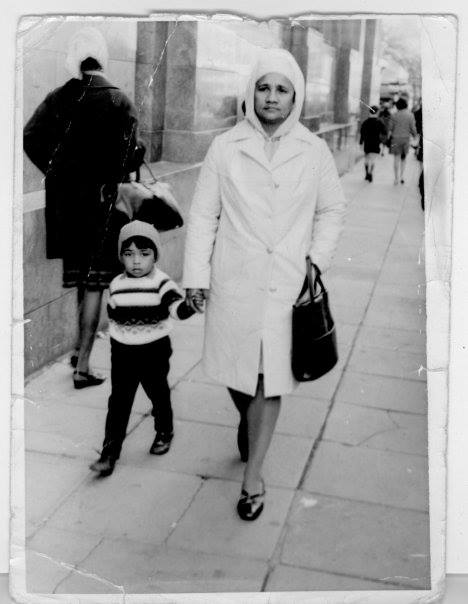

I remember a Ramadan when I was five and I was standing on the stoep of the flat we were living in in District 6 in 1970. My older siblings were already around the boeka table waiting to break their fast. The mosques in District 6 would switch on a light to indicate boeka time which is a word we used before the Muslim community in the Cape became arabised. A few minutes later, the call (or adhan) to the sunset prayer (maghrib) would sound, giving us sufficient time to eat before we make our prayers.

But I am five years old and looking out over Cape Town harbour with its many lights… As soon as I saw one flashing (clearly looking in the wrong direction) I shout at the top of my lungs, “It’s boeka tyd!” The family began eating. And even though I was not fasting yet, I ran inside to join them to get my share of boeber, sweet coconut pancakes, samoosas and other delights. My mom sits down with a stern face and says, “I don’t think it’s boeka time yet! Which mosque’s light was flashing?”

That was the last time I was left alone to look out for the light after sunset. It was also the last Ramadan we would ever spend at the foot of Table Mountain because by the beginning of 1971 we were sent the papers by the Apartheid government that District 6 had been declared a white area and we had to move to the Cape Flats. This is my earliest memory of Ramadan and when I turned six I had become one of those strange kids who wanted to fast everyday, full day.

I remember a Ramadan in the early seventies when the communities of Primrose Park and Manenberg prayed in a tent opposite my primary school. It took a while for the community to make the collections to build a proper mosque. The community would gather for tarawih (late evening prayers) in that tent dodging the water dripping from the Cape Town rain pouring down.

But while the adults were praying, the kids would be relegated to the back of the mosque. We would then tickle the toes of those in the row in front of us. This we found so amusing that we could not keep our laughter while the rest of the congregation was earnestly in prayer. My dad was one of those who resolved this by dispatching us to stand amongst the adults for the rest of the evening.

During these Ramadans, I would also compete with friends to memorise parts of the Qur’an. Even today, at the age of 50, I remember large sections of Surah Rahman (Chapter on Mercy), which I had committed to memory when I was ten years old during those Ramadans. Today, I struggle to memorise large sections of the Qur’an and find great difficulty in holding on to those parts I have memorised.

I remember a Ramadan when I was eighteen years old. My older siblings gave money so that my parents could buy meat, sweets and flowers for the Eid celebration at the end of the month of fasting. I asked my mom for money so that I could buy nice clothes for Eid. She gave me R500, which was a fortune at the time. I bought a thistle green cotton shirt with matching pants and a pair of oxblood coloured, hand-made leather shoes. I also took my dad’s red koefiyyah (cap), removed the netting inside that gave it shape and ironed it to look like the fezzes they wear in Morocco.

I thought that I looked like a revolutionary and very proud of my purchase. But on Eid day my brothers asked me, “Where are those very special Eid clothes you bought? We heard mom gave you R500.” Duh! I was wearing it! The youngest of seven kids, I only really learnt the value of money much later. But that Ramadan was also a momentous period. It was 1984. It was my matric year and nothing would be the same again.

I remember a Ramadan in 1984 when four friends (Shamiel Manie, Ebrahim Rasool, Farid Esack and I) decided that the Muslim community needed to take a clear stand against PW Botha’s government attempts to co-opt the oppressed through the Tricameral elections. The United Democratic Front had been founded the year before.

On 17 June 1984 (6 Ramadan), Primrose Park mosque saw the biggest Muslim rally (more than 8, 000 in attendance) reinforcing the Don’t Vote campaign. In the run-up to that event, I was part of a team of activists who went to various tarawih gatherings to convince Muslims to attend. In our addresses to these congregants and in our pamphlets (under the name Muslims Against Oppression) we called on Muslims to stand with the rest of the oppressed and exploited, to stand for freedom and democracy and oppose racism and apartheid capitalism.

I remember a Ramadan where we conjured up, once more, a time when earlier Muslims stood at Badr over 1, 400 years earlier to also oppose tyranny, racism and oppression. We reminded Muslims that at that battle, also in Ramadan, 300 stood against 1000. On that day, despite the odds, the forces of good vanquished the forces of evil.

I remember that in consequent Ramadans, when spirits were low because of detentions and states of emergency and police violence, we would once more remind the Muslims of the Battle of Badr. We would remind Muslims that Ramadan has a spirit that is irrepressible, that it has the ability to imbue us with a source of strength that can help us to surmount impossible odds. It was in a Ramadan then that the Call of Islam was founded.

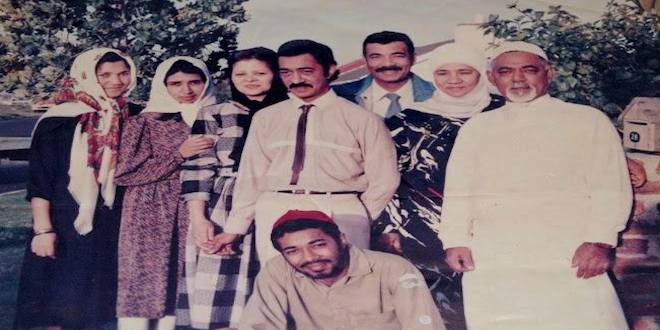

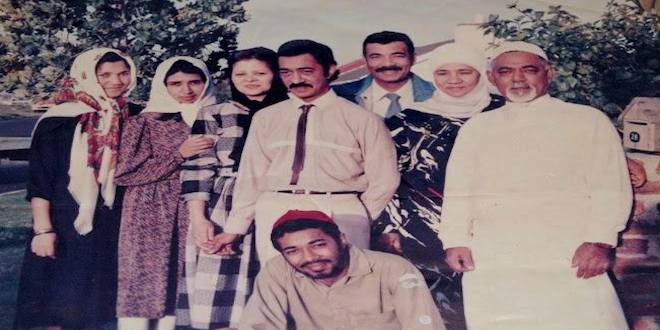

I remember a Ramadan in 1994 when my parents went for a minor pilgrimage (umrah) to Mecca. I was already married and my spouse, Sadia Fakier, was pregnant with our first child. In Mecca, my mom who was already sickly with diabetes and other ailments, had a stroke. My siblings gathered, we pooled our monies and decided that one of us had to go and help or bring my parents home. They all turned to me and said, “We are pulling rank on you and you’re the only one who is working for himself, so you must go.”

I had never been on pilgrimage before and so I sat down with my brother Faried (the middle child) to give me a crash-course. When I arrived in Jeddah, three older women who called themselves the Diedericks sisters saw me in my ihram (two pieces of white cloth and sandals) ready to go to Mecca to visit the House of God (Kaaba). They attached themselves to me by telling the customs officials that I am their chaperone (mahram). They worked out that an aunt of mine had a husband, who was also a Diedericks. According to them, this made me family.

When I got to Mecca, I found my dad waiting for me. I said, “Dad, these women want to follow me in their rituals but I only know the basics.” He said to me, “That is all you need. I will guide you the rest of the way.” As I made my seven circuits, prayed at the station of Ebrahim, ran between the two hills of Safa and Marwa, there he was giving me advice. My dad, standing, smiling, a good few inches shorter than me saying, “One more round. Almost done. Don’t worry, I have brought the scissors to cut your hair to signal the end of the ritual…”

I remember a Ramadan when I spent a blissful two weeks with my parents, able to give them support in a journey they so dearly wanted to complete. Perhaps my most memorable Ramadan because when I returned from that journey, two things were waiting for me: the birth of Bilqis Jacobs, the eldest of my four children, and the first elections in a free and democratic South Africa!

I remember a Ramadan when we stayed as a young family with now two kids in Queens Road in Woodstock. And having been the last one to leave my mother’s home, I had learnt to cook, and Ramadan treats such as pancakes and fritters are my speciality. But men standing behind a stove and cooking corn fritters is not a common sight. This meant that the kids of the area would make a line in front of our house to bring their plates of goodies to our door.

This idea of sharing cookies in Ramadan is an old ritual that I remember as a child and is still very much alive in many Muslim communities in the Cape, especially the working class areas. Ramadan is a time of sharing and there is great value in letting others break their fast with food you shared with them.

Many years later, when we moved to Gauteng, this is the one tradition that we miss and so we still try to keep it alive by driving to the homes of Sadia’s family in Joburg to take them some of what we have baked for breaking our fast.

There are so many Ramadans that I remember, most with a great fondness. Perhaps, my life is made up of these wonderful moments that make up and contribute to my enjoying of Ramadan. And despite the diabetes, cholesterol and hypertension that make fasting difficult at times, my spirit of Ramadan remain infused by these memories of light and I will endeavour to make this Ramadan equally memorable. Ramadan Kareem!

This post originally appeared on Adli Jacobs’ Facebook page, and is republished here with his permission.