During his inaugural State of the Nation Speech, President Cyril Ramaphosa announced that in an “historic†first, from the beginning of the 2018 academic year, all public schools will begin offering an African language. However, due to SONA largely being about the policy and not the implementation, there are many questions about what this actually means. The Daily Vox team takes a further look.

Could teaching children many languages help eradicate racism?

Section 29(2) of the Constitution provides that every learner has the right to receive a basic education in the language of his or her choice, where this is reasonably practicable.

NGO Section27 has said that right is “an important tool in making a break from apartheid, in which language in education was used to perpetuate oppression and inequality. In working towards the achievement of equality, and in giving specific recognition to African languages, learners now have a right to learn in their chosen language, where this is reasonably practicable.â€

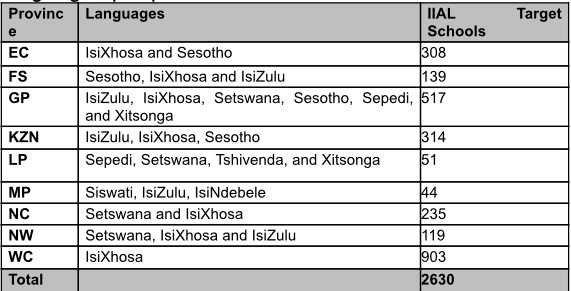

Back in 2013 during her budget speech, basic education (DBE) minister Angie Motshekga announced that a new policy would be coming into effect in 2014. This policy mandated that an African language should be taught in all schools. The policy was only formally implemented in 2016. The rollout has been slow with only 970 out of 3 558 schools which did not offer an African language now offering an African language. However, out of the 25 000 schools in the country, most were already offering a previously marginalised African language as a subject.

The policy called the Incremental Implementation of African Languages (IIAL) policy was explained at the time by the acting deputy director general for curriculum Mathanzima Mweli as overdue. Mweli said that the policy came about because of the constitutional provision in the South African Bill of Rights which allows for everyone to receive an education in the official language of their choice.

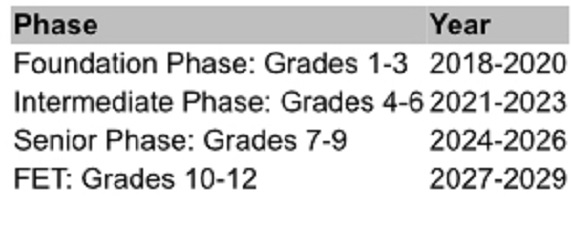

The policy planned to incrementally introduce learners to an African language from Grade 1 to 12 to ensure that all non-African home language speakers speak an African language and to provide access to languages to all learners beyond English and Afrikaans.

In the draft regulation, the policy was supposed to be implemented incrementally commencing in Grade 1 in 2015 and would continue until 2026 when it will be implemented in Grade 12.

In 2013, the plan was to introduce African languages incrementally for learners from Grade R. Mweli, who explained the plan to the parliamentary portfolio committee on education in 2013, did not answer the questions regarding the quality of the teachers as well as the availability of African language teachers.

Elijah Mhlanga, spokesperson for the DBE, said in an interview with The Daily Vox that learners are being taught a previously marginalised official African language at different language levels (Home Language level, First Additional Language level, and Second Additional Language level) and this depends on school language selection as determined by the school policy.

However, there are some problems still plaguing the implementation of this policy.

Speaking to 702’s Stephen Grootes in 2017, Mhlanga said the policy has been developed: “There is no hold-up. Remember in 2013, the minister made an announcement that she intended to force all schools to offer an African language. In 2014, we conducted a pilot. In 2015 we prepared for implementation which started in 2016. In 2017, we’ve made progress.â€

However, when questioned about whether there had been any problems with the policy implementation, Mhlanga said there were problems with getting enough African language teachers into schools.

Mhlanga said: “We have enhanced our recruitment to make sure we attract as many young people as possible to take up teaching as a profession particularly in teaching African languages.â€

Mhlanga did say they were making progress in developing the necessary learning materials like textbooks and books to be able to implement this policy.

Speaking to The Daily Vox, Mhlanga said since the inception of the IIAL Strategy, the DBE developed and distributed the IIAL Language Toolkit to all participating schools in all provinces. Mhlanga says that teachers were trained and the curriculum has been made available on the DBE website.

The Toolkit consists of Foundation Phase Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement (CAPS), workbooks, an anthology of stories, songs, and poems in all 11 languages, as well as lesson plans which include activities and exemplar informal assessment tasks.

The Daily Vox spoke to a Johannesburg teacher who has been teaching isiZulu since last year. She said that in 2017 the government provided funding and materials for the programme but the contract was not renewed for this year. Her school’s governing body (SGB) then took her on as a teacher so that she could continue with the teaching of students.

The teacher said she wishes the government programme could be reintroduced: “I so wish that they can reinstate this project so that learners can carry on with African languages because as far as I know, some of the other schools couldn’t take the teachers on as SGB so their contracts were terminated and the learners just stopped learning Zulu. Luckily mine said we want you to carry on. We don’t want to confuse them because the language [has] been introduced. I so wish the government would reconsider introducing African languages.â€

Additionally, even though many schools around the country do offer African languages, pupils still have to write examinations in a language other than their mother tongue. A linguistic lecturer from the University of Western Cape found that this put non-English or Afrikaans speaking learners at a disadvantage.

Professor Bassey Antia called on the department to introduce more teachers and examiners who would be able to give examinations in African languages.

However, due to the shortage of teachers for the initial programme of introducing African languages to schools, Mhlanga said enough teachers need to be hired to teach African languages before examinations can be administered in African languages.

There have been other voices calling for pupils to be allowed to write their examinations in their mother tongue. The Congress of South African Students (Cosas) said they would be taking the department to court to ensure this is implemented.

In an interview with the SABC, President of Cosa, John Macheke said: “We have been using English in our schools as a language of assessment but that does not mean I cannot write my question paper in Tswana, I cannot write my question paper in Xhosa,â€

The organisation said they want African languages exams to become policy and to be implemented soon.

Mhlanga said the strategy focuses on the previously marginalised official African languages but there is provision for their offering at three language levels for the National Senior Certificate by between 2027 and 2029.