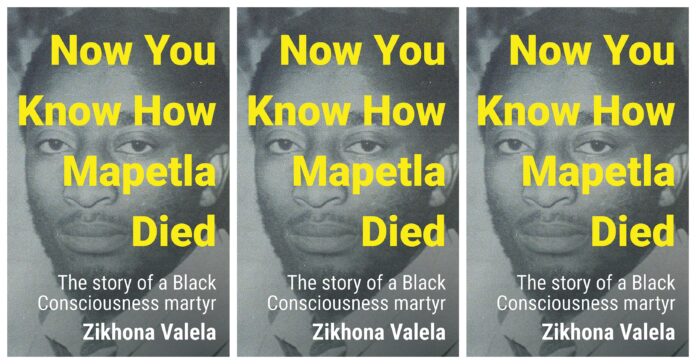

In 1976 Mapetla Mohapi was the first Black Consciousness leader to be killed in detention. His comrade, Steve Biko, tried to get justice for him, but then he too was killed. Mapetla’s widow, Nohle Mohapi- Mbetshu, has been fighting for truth and justice ever since. She was the first to testify at the TRC, yet justice still eludes the family. After his death, Thenjiwe Mtintso, a colleague of Mapetla, who was arrested in the same month, was tortured by an officer she believes was involved in his murder. But Judge Smalberger of the Eastern Cape Division later deemed her account of how his death was demonstrated to her by the apartheid police invalid, and her evidence too was invalidated. The title of this book is based on what the officer said to her as a threat. In this book, Zikhona Valela battles the erasure of this remarkable story, weaving together the words of comrades and family, mapping new understandings of the Black Consciousness Movement and of our shared history.

An extract from the book has been republished below with permission from the publishers.

Ginsberg and Zwelitsha, where Biko and Mapetla’s families lived are on the periphery of King William’s Town. Like Herschel, the small town was initially land on which a mission station was established in 1826. In 1835, Cape Colony governor, Sir Benjamin D’Urban established the area as the British Kaffraria military headquarters and also a settlement for early German settlers.

The remnants of the colonial era live on in the town’s architecture and some of its street names like Wodehouse, named after the man involved in the aftermath of the Cattle Killing, and the affluent suburb Kaffrarian Heights is an homage to the Frontier War years. It became a fully-fledged town in 1861. Some of its oldest schools exist to this day, along with the Missionary Museum, that documents the early years of the area.

The Eastern Cape is one of the earliest terrains where anticolonial resistance played out. King William’s Town was a hub of the early intellectuals who would establish the South African Native National Congress at the beginning of the 20th century.

The first black-owned newspaper was born there. King was the region where the often-forgotten prophet Nontetha was first tried in 1922 for her activities as leader of her millennial movement, which remains active to this day. A tiny statue in her honour is erected in front of the magistrate’s court, where she was tried for incitement.

Like all towns and cities during apartheid, King was segregated. The earliest instance of this goes as far back as 1898 and this was intensified in the wake of the bubonic plague. Like other small towns, it was considered the perfect place to exile and neutralise activists. The assumption was that districts like King William’s Town were impossible to rouse and that activists would simply succumb to the isolation that came with being confined to a place so far removed from where the ‘real action’ was.

It was understood that many of the activist hubs were in the urban areas like Johannesburg, Cape Town and Durban. When SASO emerged, this extended to Black (or ‘bush’) campuses like Turfloop, which were mostly found in small towns or rural areas. With banishment, activists were now forced to live in parts wherenot much political activity was happening.

Banishments proved to be a gift and evidence of just how much the apartheid regime underestimated the resolve of so many activists. The spotlight turned to rural areas and small towns – the apartheid regime unwittingly shifted the world’s attention to the periphery. Banishment simply spread the gospel of liberation further. It was a test of the urgent insistence that apartheid be brought to an end, and many activists rose to the occasion.

As for King William’s Town, the banishment of some of the most notable leaders of the BPC there was a meeting with history. The apartheid regime unwittingly facilitated the forging of a close bond between Biko and Mapetla. They met in King William’s Town soon after Biko’s banning order came into effect. The two grew to trust each other as a result of their shared commitment to bringing into existence a South Africa free from apartheid.

RELATED:

It’s 2020 and Bantu Steve Biko is more relevant than ever

Biko’s trust in Mapetla extended to his personal life. Biko’s banishment meant he was now separated from Dr Ramphele, with whom he had maintained a romantic relationship. At the time Ramphele was serving her internship at the King Edward VIII Hospital in Durban where Biko, his wife, Ntsiki Biko, and their young family had lived before Biko was slapped with banishment.

This did not stop Biko and Ramphele from seeing each other despite the distance banishment created. Mapetla was the nearest activist to him and was one of the people who enabled him to remain in touch with the movement.

After Biko was banned, the first thing he looked for was a telephone to call Dr Ramphele to say: ‘Look, we are not going to be divided and separated by this banning order, so you’ve got to make a plan so that we at least continue our relationship through regular visits.’ Ramphele took a weekend off a month in order to travel to East London, and Mapetla was one of the people who picked her up and took her to a secret meeting place, as Biko’s house was always watched. One of those secret venues was Nohle’s mother’s home. In the end they would always end up at Biko’s home anyway. The effects of banishment for Biko were such that he lived in uncertainty about what his next move would be, but he knew his work in the BCM had to continue regardless of him being restricted to the King William’s Town district. His friendship with Mapetla would prove crucial to the continuation of his work.

‘So that’s how we met’, says Dr Ramphele, who is now also an author and academic. ‘And what was striking about Mapetla was he was a handsome, super smart man. He had a wry sense of humour and was very engaging. I mean, he had big eyes so when he looks at you, you can’t help but pay attention. Mapetla had a sharp wit and nerves of steel underneath his casual exterior.

Soon Biko also wrote columns for the Daily Dispatch under Mapetla’s name. Donald Woods presents his recollections of his interactions with Mapetla to give readers a sense of what is known about the man’s work. According to Woods:

[Mapetla] walked into my office one day and offered to write a Black Consciousness column. I readily agreed to publish such a column, and he did it excellently. He was banned shortly after the column had got into its stride, and although he and his family were confined to Zwelitsha township, the authorities would not provide them with a place to live there. Eventually, after they managed to get a little house there on their own initiative, the authorities had them evicted.

Indeed, Mapetla and Nohle struggled to get a home in Zwelitsha. According to Nohle, ‘It was not easy at all until an underground ANC comrade, the late Dr Boy Mini, who was working at the Ciskei Rent Office, manoeuvred the system. He later skipped the country.”

Published by Tafelberg Publishers, the book is available online and at all good bookstores.