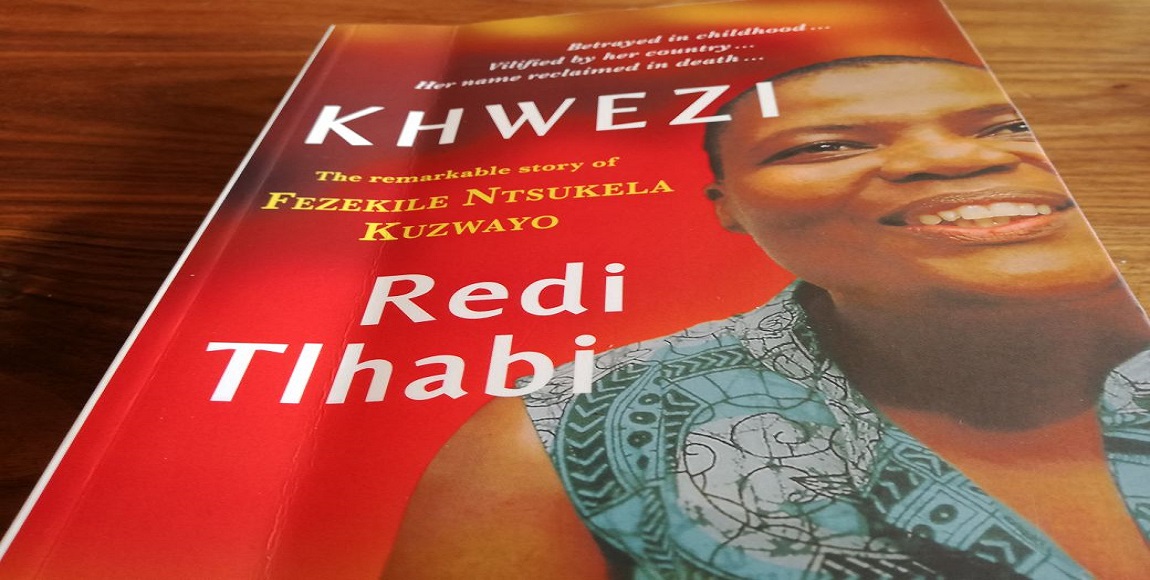

Fezekile Ntsukela Kuzwayo breathes within the pages of journalist Redi Tlhabi’s new book, Khwezi, which tells the story of the woman who accused Jacob Zuma of rape in December 2005.

Kuzwayo went through a brutal trial which Tlhabi explains over two extensive chapters. Zuma was acquitted of the rape and the act was ruled as consensual. Kuzwayo was openly hounded, called a liar and accused of setting a “honey trap” for Zuma. She eventually fled the country.

Little was known of Kuzwayo, who was known only as Khwezi until she died of an AIDS-related illness in October 2016. But Kuzwayo is much more than the woman who accused Zuma of rape all those years ago. She shouldn’t be defined by Zuma, and she didn’t want to be.

Tlhabi befriended Kuzwayo when she moved back to South Africa many years after the rape trial. Tlhabi wanted to write about Kuzwayo and Kuzwayo wanted to write about her father and her life, and so the book Khwezi was written. Tlhabi wrote the book that she and Kuzwayo had been discussing together before she passed away.

Tlhabi brings Kuzwayo to life for the reader. The story is woven together with various interviews with people from Kuzwayo’s life, her friends and family. It includes Kuzwayo’s diary entries, messages and conversations with Tlhabi. It also includes the court transcripts of the case. This rich fabric of Kuzwayo’s life is coupled with Tlhabi’s own research and analysis of apartheid and sexual violence.

She describes Kuzwayo’s talkative, warm, bubbly, and sensual nature – she also talks of her naivete and trusting nature. The book serves as a biography of Kuzwayo’s life but also, as per her request, it tells of her father Judson Kuzwayo whom she feared would be forgotten. Judson Kuzwayo was a struggle stalwart in his own right. He shared a friendship with Jacob Zuma, who Kuzwayo grew up calling “Malume” or Uncle.

Tlhabi is scathing in her criticism of the way malumes who had been entrusted to care for Kuzwayo had hurt her instead. Kuzwayo was also raped in her childhood at the ages of 5, 12 and 13 by different men she grew up with in exile.

Tlhabi describes how the heroism of the liberation struggle was tainted by the violence on women’s bodies. She writes of the way apartheid exacerbated patriarchy and how Black men felt emasculated by apartheid and sought to reclaim their masculinity through violence on women’s bodies.

However, women and their bodies are forgotten casualties of the struggle. Tlhabi writes about how the Truth and Reconciliation Commission never dealt with sexual violence and the rape of girls and women. “These are the women and girls whom the old country violated and the new country neglected,” she writes. In many ways, Kuzwayo’s story is testament to that.

Tlhabi fully believes Kuzwayo had been raped by the man who would become president. Tlhabi’s conviction is an important starting point especially because, although the book is centred around Kuzwayo, it is also about broader patriarchal structures and the sexual violence on women and children’s bodies. This is important because so many sexual assault survivors are doubted.

The book is released at an opportune time, in a year when both #MenAreTrash and #ZumaMustFall have gained a significant following. The country is seething with rage against the entitlement and violence of men on women’s bodies and a corrupt government.

It is a reminder of the continued power disparity between men and women in South Africa. Men have the benefit of the doubt, they are allowed to move on after invading a woman’s body. It is difficult, however, for women to move on. Kuzwayo is testament to how difficult it is for a survivor to move on after being subject to violence. Her psychological trauma was in her restlessness, her preoccupation with the past and her inability to fully commit to one thing. Kuzwayo found it difficult to feel settled in a particular job – she worked as a teacher for some of her life – without feeling the need for change.

The book attests to the power dynamics in the court of law, a patriarchal space where a woman is vilified for her sexual history but a man’s sexual history is accepted. Jacob Zuma escaped the trial virtually unscathed and is now the president and one of the most powerful men in the country. Kuzwayo and her mother were driven out of the country with nothing but the clothes on their backs. They returned to South Africa later, residing in the township, KwaMashu. Kuzwayo’s mother still lives there today.

The book tells the sordid tale of masculinity and the disregard it has for women and children’s bodily autonomy. It is a painful read and a powerful indictment of patriarchy in South Africa.

Khwezi is available for R175 on takealot.com and R277 at Exclusive Books.