The focus of Time of the Writer 2017 is on indigenous languages, the short story and the intersection of film and literature – and two other relevant topics. To kick off its second decade, the festival will pay tribute to the 100th anniversary of the sinking of the SS Mendi, as well as the launch of Professor Mazisi Kunene’s poem Emperor Shaka the Great in its original isiZulu.

Some changes have taken place between this year and last year, including the festival’s move from townships back to the Elizabeth Sneddon Theatre for evening events, but the goal of prioritising South African literature is still there.

In keeping with South Africa’s current social focus on decolonisation, access to education and the language debate, these are relevant and important topics to focus on for #TOW2017. The Daily Vox spoke to Fred Khumalo about his novel on the SS Mendi, Dancing the Death Drill, and to Mathabo Kunene about her late husband’s poem.

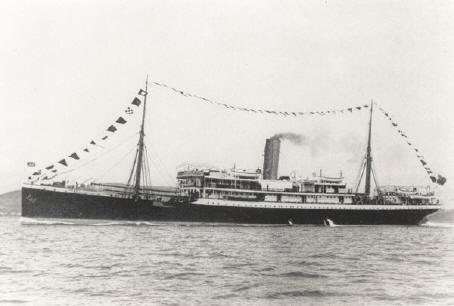

The SS Mendi was a British steamship carrying 900 black soldiers from the South African Native Labour Contingent travelling to support the war efforts. The Contingent recruited 25 000 men, and their contingency changed the course of the war. On 21 February 1917, the ship was struck by a larger ship and sank, killing 600 men.

“It’s been 100 years since the ship sunk, but not a single novel (until Dancing the Death Drill) has been published about this story! That’s a tragedy. It’s a hidden story,†said Khumalo. “I believe the organisers of the conference are sensitive to history. They want to restore this story to where it belongs: in the books of this country, but also on the lips of ordinary people who, after attending the conference, and possibly reading Death Drill would say: WOW, so this is what this SS Mendi is all about?â€

Khumalo started with the question of why black men, robbed of land and beaten into submission, would fight what was essentially a white man’s war. Though the soldiers served on the frontline performing labour, they were not even allowed to carry arms.

“It’s also important that we start telling those stories that were reduced to footnotes in our history books – because they are narratives that show the courage and selflessness of black men in the face of a dominant class that them dignity and a place under the sun,†said Khumalo.

“The tragedy was immortalised in a piece of choral music composed by Jabez Foley, from Grahamstown. We sang the song at higher primary school without really appreciating the gravity of the narrative.â€

He said it was only when he was a journalist and happened to visit Dieppe in France, that his tour guide showed Khumalo the graves of some of the survivors. “The tragedy was thus brought into sharp focus; it wasn’t just a ‘story’. The men had really existed. The graves in front of me were proof of this fact.â€

He said oral history tells us that as the ship was going down, while some of the soldiers ran for the rescue boats, a section decided to stay behind on the sinking boat under the leadership of Reverend Isaac Wauchope Dyobha. While the boat sank, the reverend is said to have told the people:

“Be quiet and calm, my countrymen, for what is taking place now is exactly what you came to do. You are going to die, but that is what you came to do. Brothers, we are drilling the drill of death. I, a Xhosa, say you are all my brothers, Zulus, Swazis, Pondos, Basutos, we die like brothers. We are the sons of Africa. Raise your cries, brothers, for though they made us leave our weapons at our home, our voices are left with our bodies.â€

it is really sad that i am only learning about #SSMENDI now, yet i can tell you about Shakespear’s birthplace.#DecolonizeEducation

— Mampho Ngakane (@MamphoN) February 26, 2017

Mathabo Kunene is currently the executive managing trustee of the Mazisi Kunene Foundation Trust, and says that the publishing of her husband’s epic poem is a historic event for Africa and the international literary platform.

“His work is often placed on the same platform as the Indian epic Mahabharata or Iliad and Odyssey which are rated as world classics in the style of epic poetry.â€

Kunene says she realised the importance of redefining the African as of equal intellectual understanding of their own history told from their languages without the colonial prejudice often expressed in books published with a singular intent to dehumanise Africans.

The first time I heard the term ‘african philosophy’ was from Mazisi Kunene way backn in early 90s, I giggled it seemed inconceivable

— Thabo (@QhaBhuti) October 15, 2016

Kunene believed that African history, told and preserved through oral methods, could not be retold in any other language other than its original. The story of Shaka, who pulled together disparate clans scattered all over the region to form one Zulu nation, and who formed the war strategies known as the Seven Principles, was immortalised through oral history. Therefore, writing the tale in an epic poem in isiZulu is one of the strongest decolonial efforts in literature.

#poetryafrica2016 #MazisiKunene deliberately wrote in isiZulu inorder to engage his soul

— Thembinkosi ngcobo (@Tnngcobo) October 10, 2016

Kunene said: “Finally, the time has come for indigenous African languages to take their own place in intellectual discourse, allowing them the liberty of referring to their own heroes at liberty.”

She said that the insistence to write close to 10 000 manuscripts ranging from nursery rhymes, love poems, epics and mythology such as Anthem of Decades all in Kunene’s language of birth now sets a precedence for the creation of a credible literary foundation for the decolonisation of present and future South Africans.

The Daily Vox is the official media partner of the 2017 Time of the Writer festival, which runs from 13-18 March 2017. For the full programme, click here.