The Ruth First Memorial Lecture was, once again, extraordinary. Each speaker presenting on the theme, “Rage and Violence in our Politics†produced papers that spoke to the beating pulse of young South Africans. The lecture pushed the boundaries of academic thought, while at the same time offering a compelling critique of the way things are.

The Daily Vox team reflects on their Ruth First 2016 experience.

The rainbow nation lie and brewing rage

We learnt from last year’s Ruth First Memorial Lecture that the rainbow nation is a myth, but it was only at this year’s lecture that we got to look at some of the repelling effects thereof. In post-apartheid SA, blacks, whites, coloureds and Indians are supposed to sing hold hands and sing kumbaya and or do the Madiba jive under the rainbow nation, which Fellow Lwandile Fikeni’s paper describes as a silencing project that aimed to make black people un-remember all that had happened to them. The after-effects of this project becomes the “main relational aesthetic practice between citizens, between citizens and state, between citizen and institution.â€

People cannot be told how and when they should deal with their oppression and it is through gestures and slogans of racial harmony that black people’s experience of racism, systemic exclusion and social violence are erased. “Rainbowism becomes a way of disallowing black people the space to speak about their pain and oppression. And it is this silencing which comes in the form of commandment which gives the rainbow an aesthetics of racial harmony, which is, in fact, a way of policing of black rage,” said Fikeni.

This year’s Ruth First lecture, like the one before it, was nothing short of lit. The topic of conversation, of violence and rage, is one that is part of the lived experiences of black South Africans and therefore crucial to the conversations we should be having across the country.

During the Q&A session, someone from the audience asked about justifying the cost to the destruction of university property. In response, Lwandile Fikeni shut him down – saying the question is silly and irrelevant compared to the cost of poverty. This mindset is one that many people still hold in SA, where they value art and property more than their fellow South Africans.

And of course, I can’t leave out Leigh-Ann Naidoo. Her speech really struck me, especially when she spoke about how student movements need to use violence as a way to build a better future. Most people just associate the student movements with violence and destruction while she portrayed it as a gift that universities never knew they had.

The Annual Ruth First lecture always stirs up historical pain and a deep sense of hope in me. Although the event commemorates the life of Ruth First as an anti-apartheid activist, it has evolved into a safe space where different generations meet to discuss the state of the revolution.

When Leigh-Ann Naidoo gave her keynote address, she spoke about the Fees Must Fall movement as the imagination of a future nation. Not only did this affirm the work of fallists, but she mapped out a strategy for protests beyond the usual shut down and disruption of academic programs. She spoke of using that time to plot and to draft the workings of a new society. Nolwazi Tusini gave a disappointing account of the contribution of what she calls the “the 80s cohort” where she practically erased the work that they continue to do on a daily basis. Her artful comparison of Roots characters to the different generations of black students who were privileged enough to attend elite institutions of higher learning was painful to listen to. I struggled to find gems worthy of tweeting in her speech. She half-heartedly started a conversation that I hope someone responds to in a more eloquent manner someday.

Lwandile Fikeni spoke about rage in a fashion that was so familiar to student activists. He affirmed their new theoretical language in a manner that affirmed their school of thought. The level of research and consultation was evident in the way that he referenced the canon of resistance culture from the generation of our mothers and grandmothers. His use of vernacular spoke to the culture of rejecting the current institution as we have come to know it. By the end of the night, he charged the audience with the kind of fire that gave birth to the student movement last year. The night ended with singing struggle songs on the Great Hall stairs and with a great sense of responsibility lurking in the air.

I found that the entire experience left one feeling more humanised after – with a greater deal of empathy for oneself and others who’ve internalised the everyday harm of systemic violence. It’s rare that the “uglier†emotions be unpacked beyond their aesthetic appearance towards a radical questioning of their origin.

While I believe every speaker touched on an important aspect that no doubt spoke to different people on varying levels, I was especially moved by Leigh-Ann Naidoo’s piece which, for me, was one of the most accurate illustrations of fallists, their attitude and vantage point. In my opinion, it’s one of the most important reads for young South Africans this year. I enjoyed how she managed to channel and recast a stigmatised sense of rage into notions of vibrance, uncompromising optimism for the future and a refusal to be determined by the limitations of the present. I believe this specifically was important for many to hear after facing a lengthy period of internal and external assault by media and the status quo’s social power. The fallist paradigm that’s described is one that needs further fleshing out, if it is to become a truly whole philosophy.“

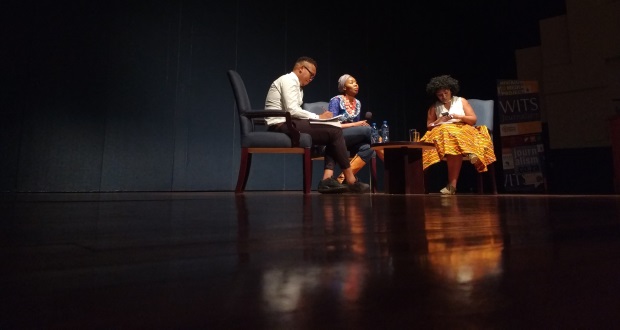

Witness the “litness” that was Leigh-Ann Naidoo, Nolwazi Tusini and Lwandile Fikeni here: