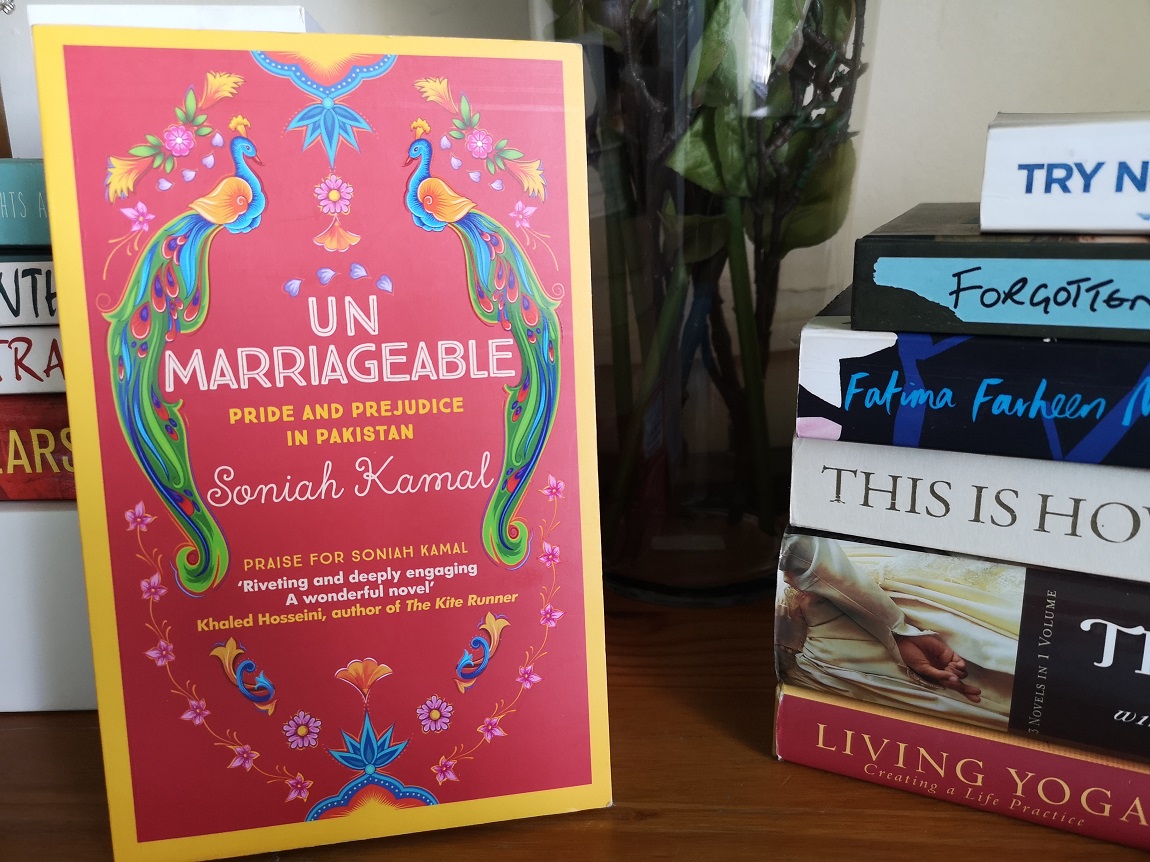

Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice is perhaps the most beloved amongst classic English literature. There have been prequels, sequels, and variations of the story with zombies, religious conversion, Bollywood, and even S&M and slash fiction. This year Soniah Kamal gifted readers with Unmarriageable: Pride and Prejudice in Pakistan: a complete retelling of Austen’s book set in Pakistan in the 2000s.

Kamal has cleverly converted Austen’s characters into their Pakistani parallels. The Bennet family became the Binats. The five sisters Jane, Elizabeth, Mary, Kitty, and Lydia became Jenazba, Alysba, Marizba, Qittyara, and Lady. Like the Bennets, the Binat’s financial and social standing is in tatters. In Unmarriageable, the situation is because a family scandal that cost the Binats their fortune. Mr Darcy is the wealthy, arrogant, and good looking Mr Valentine Darsee.

The story is a colourful retelling of the familiar.

Alys teaches English literature to schoolgirls, hoping to inspire her students to dream bigger. When the Binats receive a wedding invitation from one of Pakistan’s moneyed social elites, Mrs Binat is set on snagging wealthy, eligible bachelors for her unmarried daughters. During the celebration wealthy bachelor Fahad “Bungles” Bingla’s becomes quite taken by Jena, to the chagrin of his friend Darsee, who is unimpressed with the Binats. When Alys accidentally overhears Darsee’s dismissal of her, she doesn’t think much of him either. While the Binats hope for Jena to land a proposal, Alys discovers there might be more to Darsee than she initially thought.

Unmarriageable is a homage to Austen’s classic: addictive, charming and superbly written. It will have you laughing out loud. Unmarriageable also makes insightful commentary about colonialism, class, love, marriage, and feminism. Readers will delight in the startling similarities between Regency England and modern-day Pakistan. Kamal does great justice to the sparkling language, unforgettable characters, and social commentary that Austen is famous for.

Kamal and Jane Austen

As an award-winning writer, Kamal is no stranger to the literary world. Kamal also serves as an ambassador for the Jane Austen Literacy Foundation, founded by Jane Austen’s fifth great niece Caroline Knight to honour Austen’s relationship with libraries and literacy.

Needless to say, Kamal is an avid Austen fan and found writing the book incredibly daunting, she says in an interview with The Daily Vox.

“It’s not an ‘inspired by’ or a continuation, it’s a parallel retelling. It’s very much the entire story of Pride and Prejudice set in Pakistan. To take something like that and reorient it was very intimidating,” Kamal says.

Kamal first received her 70s edition copy of Pride and Prejudice (red with gold writing), at age 14. She didn’t immediately get stuck into it, but often paged through the illustrations and read the captions. Finally at 16 she read the book, and that cemented her admiration for Austen’s works. Mansfield Park is her favourite. Unmarriageable is flecked with nods to Austen’s body of work, Mansfield Park included.

As a reader and a writer, Kamal admires Austen’s works. “Austen’s insight into human nature and the universality she has captured is incredible. There are things about human nature that you recognise on every page. She voices her books with such brilliant satire, her books are a laugh a minute. But I also think that her pacing, her writing is very modern. She tells her story without telling you how to think about the characters, she leaves that up to you. There’s no endless boring pages, she does not give huge descriptions, it’s basically just dialogue,” she says.

What shocks Kamal the most is when she hears that Unmarriageable was a gateway for some readers to read Austen or Pride and Prejudice for the first time. “Out of all the things I thought, that is one thing that never crossed my mind,” Kamal says. But readers need not fret if they aren’t fans of Austen or Pride and Prejudice, Kamal wrote Unmarriageable as a standalone novel. Austen aside, Kamal reads widely since childhood.

Her eclectic reading tastes come as a result of her international education. What stood out was that Kamal had never read books in English set in Pakistan.

The reason Pakistani-born Kamal grew up speaking English is because of Indian colonial history, long before partition.

Unmarriageable and Pakistani colonial history

“Unmarriageable opens up with Thomas Babington Macaulay’s policy of implementing English in colonial nations in order to create confused individuals,” Kamal says. Macaulay, who served as a member of the governor’s Supreme Council in India between 1839-1848, published the “Macaulay Minute” in 1835. In it, he supported instituting English as the official language in India, and using English as the medium of instruction in schools.

For Kamal, this, coupled with her international education, meant that she grew up speaking, reading and writing in English instead of Urdu or Kashmiri which her parents spoke.

“Your written language is a record of your history. If you bring up people who cannot read that language and can only read the language you’ve given them then your revisionist history, or however you want to translate that history, becomes a history that they become aware of. They can’t read or speak or understand another language. This was a very concentrated policy on how to bring up people who didn’t have an idea of who they were,” Kamal says.

Without books set in Pakistan and written in English, Kamal started converting things while she read. “If I read bonnets I would say dupattas, if I read sandwiches or scones I’d think samosas,” Kamal says. Pride and Prejudicewas such a Pakistani book for Kamal. She says, “It’s a novel about a mother who is desperate to see her five kids married”. In the back of her mind, Kamal knew she wanted to pen a Pakistani Pride and Prejudice.

Writing the characters of Unmarriageable

Since the novel came out on January 25, Kamal has attended book clubs, readings and literature festivals. She says it’s always interesting to see how different cultural groups experience Mrs Binat. “Desi people, Pakistanis specifically, don’t find her melodramatic or exaggerated. People not of the culture are like, ‘OMG, she’s so over the top’. It’s fascinating to see that whichever culture you come from, the characters you’ve written resonate within those cultures,” Kamal says. Kamal thought she wrote a tamed version of Mrs Bennet. “I thought, ‘If I start showing the theatrics that [Pakistani] mothers are capable of, then she will really be over the top.’”

Charlotte is Kamal’s favourite character in Pride and Prejudice. “She’s supposed to be seen as the poor, lacklustre, non-brilliant friend who doesn’t have any choice. But she’s one of the characters with huge agency in the novel,” Kamal says. Charlotte ends up snapping up Elizabeth’s spurned proposal from Mr Bennet’s distant cousin and well off clergyman Mr Collins. Kamal was smitten by Charlotte’s drive. “Not only did she have the ‘balls’ to get someone to propose to her, but when Elizabeth looks down on her choice she doesn’t care. Charlotte knows that where she is in life, this is a good thing for her,” she says.

Kamal’s love for Charlotte comes through in the way she writes Sherry. In Unmarriageable, Sherry is Alys’ best friend, a single woman in her forties who wants to marry to better her family’s social standing and have socially sanctioned sex.

Regency England vs modern-day Pakistan

Like in Regency England, there is still pressure to marry in Pakistani communities. This is partly because in Islam premarital sex is unlawful, but also because of age and maternity. But more and more women are waiting because now, women can work in Pakistan.

“Many women who have good jobs and learning capacities are waiting to get married,” she says. To reflect this shift, in Kamal’s book most of the female characters work. So much depends on the class you’re born into and the family within that class when it comes to marriage, and other things, she says. In her book, Kamal reflects the realities and expectations from a more working class perspective, as Sherry is born into, and even the lifestyles of the moneyed elite.

Importantly, Kamal creates a window for South Asian representation in the classics. It wasn’t just a “fun project” for Kamal, it was a “reorienting and remapping” of identity. Kamal is comforted by a remark made by a professor at her Seattle reading that Unmarriageable was probably Macauley’s worst nightmare. “Here I am taking an Austen novel and turned it into a Pakistani version. You can’t be any more unconfused than that,” Kamal says.

Published by Allison & Busby, Unmarriageable retails online and in good bookstores.