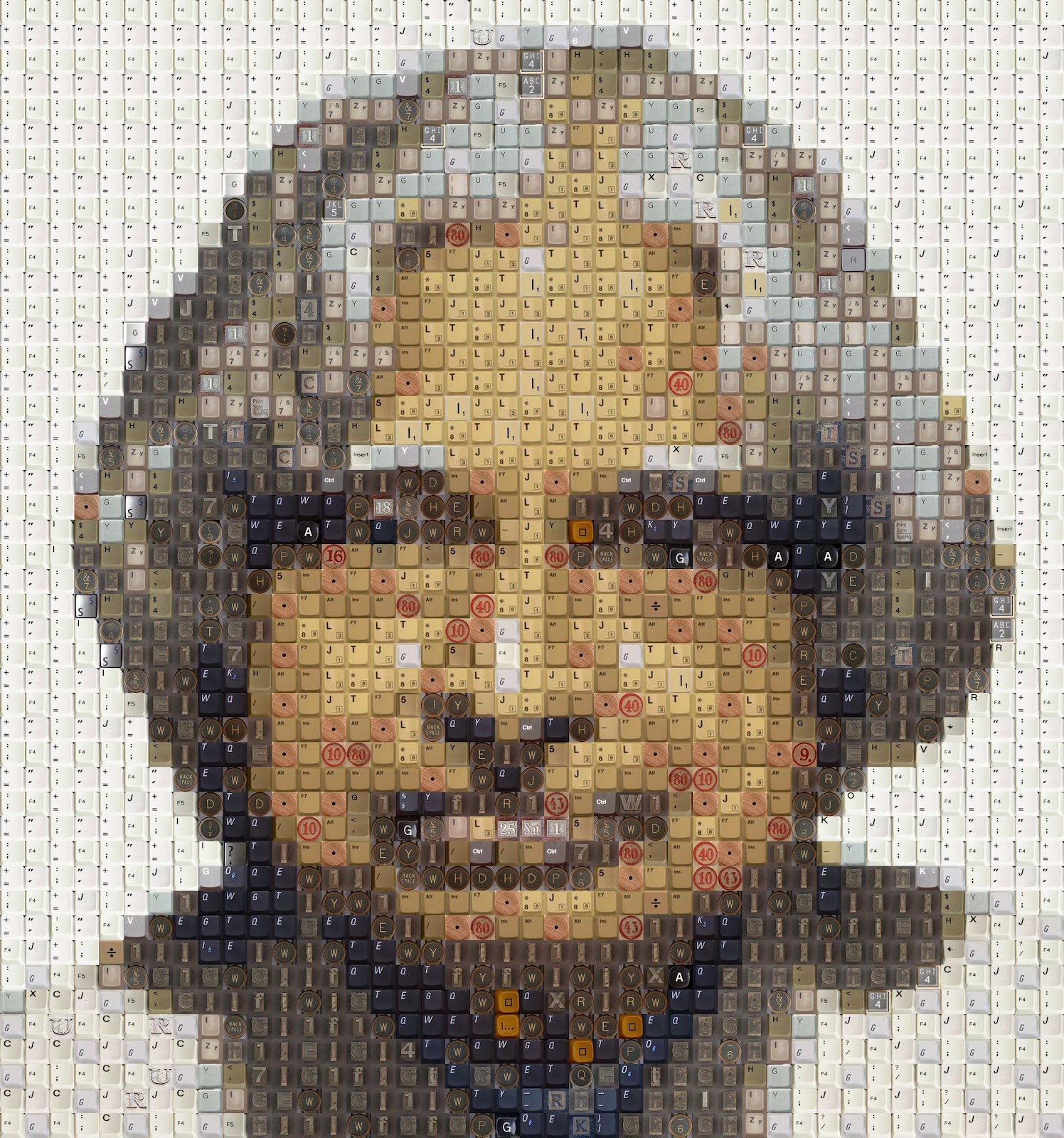

Ahmed Kathrada, affectionately known as Uncle Kathy, passed away in the early hours of Tuesday, 28 March 2017. Kathrada, one of the Rivonia trialists, a struggle hero, and contemporary of Nelson Mandela and Walter Sisulu, was 87 years old.

Kathrada had been hospitalised earlier this month following surgery. He suffered complications and contracted pneumonia, which caused his condition to deteriorate.

A close friend of Kathrada, and fellow Robben Island prisoner Laloo Chiba, who has known Kathrada for over 60 years, said:

“He has been my strength in prison, my guide in political life and my pillar of strength in the most difficult moments of my life. Now he is gone.â€

Kathy was a tower of strength and a source of inspiration to many prisoners, both young and old.” – Walter Sisulu

Kathrada was born in the town of Schweitze-Reneke, about 320km from Johannesburg, in what is now the North West province. In the foreword to the Jannie Momberg book From Malan to Mbeki, Kathrada wrote about being “wrenched away†from his mother and father at age eight, when he was sent to live with a relative in Johannesburg to continue his schooling.

“Apartheid had decreed that an Indian boy could not be admitted to the White or Black schools in Schweizer-Reneke. My first traumatic awakening to the evils of racism took place at a very tender age. In later years, I vowed to use my life to oppose it however I could,†he wrote.

The Johannesburg area he moved to was a politicised one and by the time he was 11 or 12, he’d started handing out political pamphlets and putting up flyers around town. He joined the Young Communist League (reportedly at the age of 12) and later became a member of the Communist party. Kathrada was heavily involved in the Passive Resistance Campaign, which sought to contravene a set of discriminatory laws, and by the age of 17 he’d already served a month in prison for civil disobedience. By that point he was already well acquainted with struggle stalwarts like Yusuf Dadoo, Cissie Gool and even Nelson Mandela.

Kathrada enrolled at Wits University but dropped out again to pursue political activism full time. He would later go on to complete a BA, B. Bibliography and two Honours degrees while serving a life sentence in Robben Island.

Kathrada joined the Defiance Campaign in 1952 and was sentenced to nine months in prison, suspended for two years. He was banned two years later. This meant was that at 25, Kathrada was prevented from taking part in politics or attending gatherings of two or more people. He was charged with treason in 1956, and acquitted after a lengthy trial. Then in 1962, he was placed under house arrest. He had to remain indoors from 6pm until 7am the next day, could not have any visitors at home, and had to report to the police station each day at 2pm. He soon went underground.

Then, on 11 July 1963, he was apprehended in a raid on Liliesleaf Farm. Kathrada, together with nine others including Mandela, Sisulu and Govan Mbeki would later charged and convicted at the Rivonia treason trial.

Speaking of his initial 90 days in detention, Kathrada said: “The abiding thought during those lonely and anxious days was my responsibility to myself, to my family, to my comrades, to my organisation, and most importantly to the struggle.â€

Seven of the trialists ended up on Robben Island. Kathrada, at 34, was the youngest of the group, but as he pointed out over the years, he was not the youngest at the prison. Some, like deputy chief justice Dikgang Moseneke, were held there from the age 16.

Deprivation and discrimination were standard practice in prison. Black prisoners were only given porridge to eat, while coloured and Indian prisoners were allowed to eat bread. Kathrada would share his extra bread with his fellow prisoners when he got the chance.

“If I had to use a single word to define life on Robben Island, it would be ‘cold’. Cold food, cold showers, cold winters, cold wind coming in off the sea, cold warders,†wrote Kathrada in his memoirs.

Kathrada has said that one of the greatest deprivations for prisoners during those years was the absence of children.

On more than one occasion, he related the story of how, in 1982, on being transferred to a section of the women’s prison at Pollsmoor, the trialists for the first time heard the sounds of children, laughing or crying, nearby. It was there, when a lawyer friend visited with his young child in tow, that Kathrada finally held a child again, for the first time in 23 years. “It’s an unnatural world without children,†he said.

Kathrada was 34 when he was sentenced to life imprisonment. When he was released, 26 years later, he was an old man of 60. Life had passed him and the other Rivonia trialists by.

“Many of us are often asked if our struggle and sacrifices were worth it. My reply is: it is true that prison, exile, and other experiences were hard, but at least we survived to see freedom. What about Chris Hani, Ruth Slovo, Dulcie September, and the hundreds of school kids who were killed in the 1976 Soweto uprising who did not? 18 years in the life of an individual is a long time but in the life of a country is very short.”

Kathrada has no children. But he was fond of his godchildren and his grandnieces, who grew up with him as their grandfather. He loved chocolate and ice-cream and would often spoil them with it.

After apartheid

When apartheid ended, Kathrada became a member of parliament. He served as chair of the Robben Island Museum Council and later as a parliamentary counsellor in the Office of the President. He subsequently withdrew from national politics but he continued to be an active member of civil society. Kathrada wrote books, gave speeches, opened libraries and wrote forewords to other people’s books and memoirs. His foundation, the Ahmed Kathrada Foundation, has focused on championing and deepening non-racialism.

In his writing and his speeches, Kathrada had a tendency to rattle off lists of people who had been lost during the struggle. It was as though he were constantly trying to reiterate the sacrifices of those who are often forgotten in Mandela’s shadow, and to remind us of the violence endured by the freedom fighters of yesteryear.

Joe Gqabi, he was my neighbour on Robben Island, assassinated in Harare; Ruth Slovo, we grew up together in the Young Communist League, she was killed by a bomb, letter bomb in 1982; Vuyisile Mini, fellow accused in the Treason trial, he was hanged in April 1964; Flag Boshielo who was captured by the enemy and never seen alive again; Patrick Malao, former Treason trialist, killed in combat; Babla Saloojee, killed by the security police by being thrown off the building of the Security Police Headquarters; Prakash Napier and Yusuf Akhalwava, killed by the bomb, by a bomb; and there are many more that I cannot remember, well those were just a few who I knew personally…

Kathrada wasn’t easily satisfied with the gains made after the end of apartheid. In March last year, he wrote a letter to President Jacob Zuma saying he felt “obligated to express his concernsâ€. He implored Zuma to “submit to the will of the people and resign, saying his “continued stay as president will only serve to deepen the crisis of confidence in the government of the countryâ€.

He was known for his interest in young people’s struggles and was frequently seen at student events. While his struggle compatriots often referred to him as Kathy (and Mandela referred to him as Madala), among young people he was simply “Uncle Kathyâ€.

The Daily Vox reporter Aaisha Dadi Patel met Kathrada at several campus events, including during the Fees Must Fall protests of 2015.

“It’s a funny thing, to meet someone who is a living legend, whose history you’re familiar with from your school curricula, and realise they’re basically a grandfather figure, with a whole lot of history and a tonne of hope for young people,†she said.

“What stuck out for me with Uncle Kathy was his unwavering belief in the youth, and the way that he always went out of his way to encourage and support us. He was never dismissive or patronising, but instead always attentive and truly invested in what we had to say.â€

Kathrada made it a point to come to Wits University at the height of the student protests in both 2015 and 2016, to demonstrate his support for the student movement.

“I came here knowing that the students are very determined, and I’ve been inspired by the spirit here,†he told Dadi Patel after one of the protests.

Stooped and bespectacled, with by then thinning hair, Kathrada was a prominent figure on campus, who inspired students leaders across the board, regardless of their political differences.

Kathrada always maintained that he “didn’t deserve to be elevated to the status of what I call the ‘A Team’â€. But he lived a selfless life, and from the earlier age made myriad sacrifices so that we could live in peace and not suffer the injustices of a ruthless and discriminatory state. Still, he was well aware that the struggle is not over and he implored South Africans to be active citizens.

“The preservation of democracy in our country, as elsewhere in the world, is not guaranteed, nor should it be. It is yet to be fought for, with integrity and selflessness,†he said.

Kathrada is survived by his wife, Barbara Hogan.