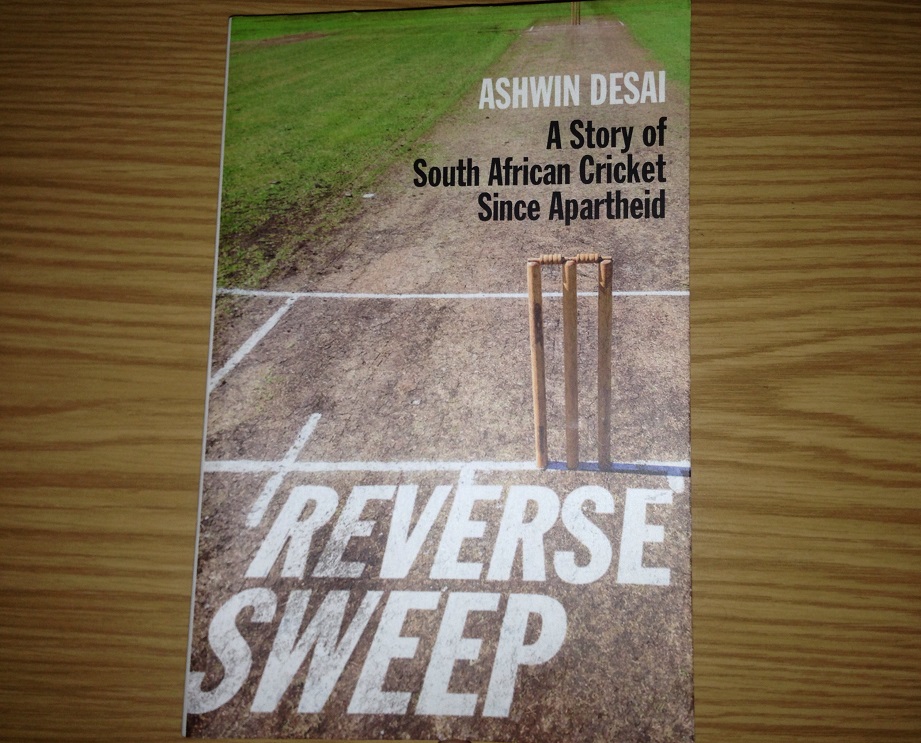

Ashwin Desai’s newest book, Reverse Sweep: A Story of Post-Apartheid South African Cricket is a compelling read. It traces the history of cricket in South Africa. It goes from the rogue tours that took place during apartheid to the post-apartheid transition of transformation and inclusion right up until the events of the 2016 cricket season. The Daily Vox team takes a look at five things we learned about the history of South African cricket from the book.

1. The Rogue Tours

Black cricketers came to realise that in a racist society cricket was more than just playing the game. It was about confronting racism with non-racism, about keeping the game alive despite the conditions – the book reads.

Rogue tours were organised by the white South African Cricket Union (SACU) to bypass sporting bans against South African teams. Many of the players with these tours – which included England’s Geoffrey Boycott, Michael Gatting, Australia’s Kim Hughes and West Indies’s Lawrence Rowe, as well as journalists like Australian journalist Chris Harte who travelled with the Australian rogues tours of 1985 and 1987 – often depicted a one-sided picture of the country.

Harte reported meeting a black man who was a supervisor at an ostrich farm during one of the tours, and based on this one interview, Harte was convinced that black people did not want to vote. Hughes also said at the end of 1986 tour that “Cricket isn’t the beat of blacks.” The realities of the time were ignored by those living in their bubble of privilege.

The rogue tours were also justified as bringing funds and development to townships cricket teams, yet this was far from the truth. It was a case of white privileged cricketers enforcing their narratives with the complete erasure of the struggles of black cricketers.

2. Ali Bacher: the case of a mistaken hero

Administrator of the newly formed United Cricket Board of South Africa, Ali Bacher has been portrayed an image of an innocent bystander who realised too late the horrible effects of the apartheid regime and who actually tried to help black communities develop their cricket.

Yet Bacher knew the reality of what was taking place and was in fact instrumental in organising the rogue tours. Grant Farred, a South African professor of Cornell University says: “Bacher, of course, is anything but naive; he simply has a cynically selective political memory, Moreover, he is in a position of cultural authority from which he can insert massive silences into black South African history.” This was evidenced by Bacher thinking of emigrating to Canada after the Soweto Uprising.

Bacher not only managed to survive career-wise post-apartheid but he also managed to flourish through his contacts in high places like then- Minister of Sport and Recreation, Steve Tshwete. Bacher, it seemed, was one of the greatest ‘winners’ in cricket during apartheid and even in the period after, managing to play everyone around him like a chess board.

“But then everything that Bacher does is dressed up in hero’s language,” writes Desai.

3. The fight for black cricketers after apartheid

“Would Hashim Amla and Vernon Philander trace their lineage back to a history from which their fathers were excluded?” asks Desai.

Once apartheid had ended, another fight seemed to start. Black cricket under apartheid has been suppressed in many ways and had to build up from nothing and yet now still compete with white privileged cricketers. Black players weren’t regarded as “good enough”, but the circumstances of their training and playing were not taken into account. The legacy of black cricketers during apartheid were also completely erased or were being told by white apartheid sympathisers.

4. Black skin, white helmets

“The last two months can be described as the worst in my entire life. In the change-rooms we are made to feel we’ve encroached into their territory. However, when we are in the eye of the public a totally different picture is painted to the masses,” Desai quotes an unnamed black Proteas player.

Although transformation and inclusion was top on the agenda post-apartheid with black players being assimilated into the new cricket squad, racism still persisted. Many of the white players, including celebrated Proteas wicketkeeper Mark Boucher, could not seem to fathom the privilege their whiteness afforded them.

Garnett Kruger, a coloured player criticised CSA after being picked for a test match in 2007, saying that there were were cliques in the squad which usually consisted of the senior white players in the team. Boucher however, was not interested in Kruger’s criticisms, and even defended the clique that existed at the time, not realising that coloured or black players would be dropped after a few bad games while white players would continuously be given chances. Imaginary white disadvantage also arose which means exactly what it sounds like. It’s difficult to know that some of the recent greats of the game like Boucher were guilty of this.

5. Failures of the post-apartheid administration

“When a newly liberated country meets on the turf of its old colonial master, as James would have it, ‘much, much more’ than cricket is at stake,” Desai says in the book.

The ANC government, current Sports Minister Fikile Mbalula and post-apartheid administrators have failed local cricket. Black cricket is still not being developed, whether in town schools or any form of grassroots level. The best players, whether black or white, are still mostly coming from private schools while the great talent that might exist at public schools, township schools and in the rural areas are laying dormant.

One such player is Temba Bavuma who might have gone through Cricket South Africa’s development programme, yet ultimately received most of his formal training from top private schools in Cape Town and Johannesburg.

Bavuma himself says: “I attended top private schools – and had access to quality schools and elite coaching. There were boys who were much more talented than I was, but early exposure gave me the edge over my peers who remained in the township.”

While Mbalula’s ban of the hosting of international tournaments until transformation standards are met might help, the government hasn’t done much to help develop a good infrastructure of cricket at schools.

The book is available at Exclusive Books, Takealot and Amazon.