The ruling African National Congress (ANC) is forging narratives to create a certain viewpoint. The purpose is to make sense of the past in ways that make their present actions more plausible. BY Thand’Olwethu Dlanga.

OPINION

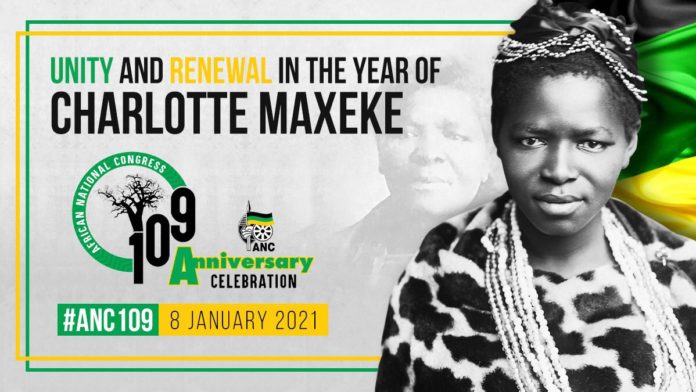

In 2020, they did it with the “public’ statue of OR Tambo” and this year, 2021, it is the ‘Year of Charlotte Maxeke’ narrative. Mama Charlotte nee Manye Maxeke, the 20th century African nationalist, theoretician and member of the Bantu Women’s League, does not singularly deserve a whole year of celebrations that uses public resources. There are other women in the liberation struggle who deserve to be celebrated in their own right. They shouldn’t be footnotes to her.

Be that as it may, my protest is not entirely about the expense involved in unveiling these symbols. It is more about the curation of public memory and heritage in post-1994 South Africa.

The Charlotte Maxeke narrative, as with the OR Tambo statue, is a post-’94 government-sponsored struggle. It relies upon a triumphalist perspective by the ANC. It presents liberation history as a dichotomy of the ‘right history’ and wrong history. The ‘right’ one being that of the Charterists and all else is wrong.

RELATED:

Heritage Day- What heritage are we celebrating? Or are we coerced to celebrate, Mr President?

The unveiling of 2021 as the ‘Year of Charlotte Maxeke’, as with that statue in 2020, demonstrates that the state apparatus is being manipulated to harness the dominance of the ruling party. This neglects and undermines the contribution of other liberation movements and people to influence post-apartheid public memory.

These two instances confirm a continuous political hegemonic narrative of the liberation project for party political ends. If it were not the case, why place ANC signs on a ‘public’ heritage or present Mama Maxeke celebrations within the ANC political ‘province’ of ‘unity, renewal and reconstruction’? It is because they are in the terrain of politics of memory. These politicians want to keep and inspire a narrative and a ‘moral excellence’ of the ruling party against the decolonisation stances of other organisations.

In April 2021, in an ANC rally, Pres Ramaphosa stated: ‘Charlotte Maxeke was an outstanding leader, we cannot talk about the history of South Africa without talking about her contribution’. This is a beautiful tribute to Mama Maxeke. Such an acknowledgement to persons of the liberation struggle is highly appreciated, but why not do it across the political spectrum?

South Africans would then know that Mama Zondeni Sobukwe, Mama Komikie Gumede and Mama Nomvo Booi were outstanding leaders who made a central contribution to South African liberation history. These Africanist women, like Maxeke, are ‘true embodiments of African womanhood’. They made intellectual contributions about the place of African women and broader issues in South Africa.

What I pursue to highlight is that the voices of the liberation struggle were not solitary affiliates of the Charterists, as is being depicted today. They also emanated from other ideo-political persuasions. Since 1994, the curation of public memory has reflected time and time again that when the ANC government says we ‘telling the world that we have not forgotten our heroes’, ‘our heroes’ implies Charterists and nobody else.

If the ruling party were so confident about its liberation struggle credentials, why do they not allow for the promotion of other liberation heroines such as Hilda Mngaza, Zubeida ‘Juby’ Mayet, Lauretta Ngcobo and others? If the country exists under democratic rule, why not democratise the liberation struggle’s history?

The commemoration of the 150th birthday anniversary of Charlotte Maxeke has little to do with public interest. instead it’s everything to do with entrenching the ANC’s credentials in our public memory. It is just a scheme of legitimation, since memory is a powerful weapon.

Featured image via Twitter.

AUTHOR’S BIO: Thand’Olwethu Dlanga is a pan Africanist and a student of History, Politics and Philosophy. His academic interests is in the field of memory and how memories are curated and constructed in post-legal apartheid South Africa. He is also an online talk show co-host (YouTube PontDePolitique) and he writes in his personal capacity.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policies of The Daily Vox.