Almost four months after the Heher Commission completed its work and gave President Zuma its report, the fundamental issues raised by the #FeesMustFall movement in 2015 remain unaddressed. The preparation of the mammoth 752-page report, now freely available, appears to have been an exercise of holding student protestors in a state of suspended animation, say Gugulethu Mhlungu and TO Molefe.

The exercise could prove costly in long run as fallists aren’t especially known for easily backing down from their demands, because they know they are just and justified.

The most fundamental of these demands was free, quality, decolonised higher education.

To be fair, the commission does not altogether rule out the possibility and necessity of fee-free higher education. In fact, it looks at what would need to happen to make education more accessible. The state, higher education institutions and students seem to agree that cost-sharing is a more equitable model. Closing the gap between what the private sector contributes to the public higher education sector and what it derives is one where there appears to be consensus. The benefits the private sector derives from public higher education currently dwarf its contributions to funding it.

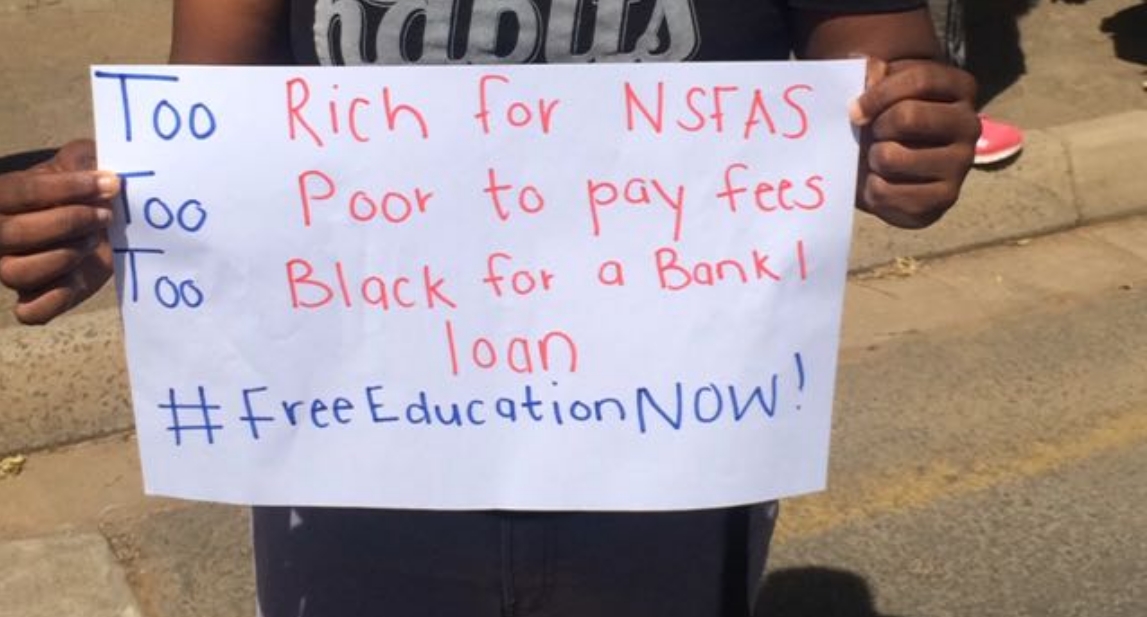

However, if there were ever a contemporary example of what intersectional politics could look like, and what the practical limits and faults are, #FeesMustFall was it. The movement articulated that access to higher education becomes inequitable when the socioeconomic conditions of the country disadvantage the poor and, increasingly, the middle-income – who are misread as actual middle class only because the media earnings in the country are so low.

R3 193 per month is, according to research by Andrew Finn, what the person in the literal middle would be earning were all working-age South Africans were lined up from lowest to highest earning. And if you look only at black people, median income falls to a figure closer to R2 500, barely a whisper above the poverty line of R992, let alone enough to afford higher education or the basket of other socioeconomic rights promised in the Constitution.

The call #FeesMustFall sounded, therefore, was not only about inequality and how it limits the aspirations and rights of poor and middle-income students, who are overwhelmingly black. It was also a demand – aggressive and confrontational it may at times been – that we engage with the history of how inequality was constructed in this country and respond to bend the arch of the moral universe towards justice. Originally articulated by Martin Luther King Jr, the idea that the moral universe bends towards justice has lulled many into believing the outcome fated; that it happens without activism or action on the part of those of us who live in this universe.

Many higher education institutions and the state responded to this important call from #FeesMustFall not with thoughtful responses, but with police brutality and other attempts to silence dissent.

University vice-chancellors chose to prioritise a narrowly defined idea of the “academic project” over social justice. As, too, did many of the towering intellectuals of decolonisation, whose livelihoods are tied to this underdeveloped, corporatised idea of what the academic project is. Instead of lending their intellect to bolster #FeesMustFall’s demand that we engage with history and act to bend our moral universe towards justice, they chose instead to liken fallists to Boko Haram, or describe them as absolutists intent on violence and burning.

The state, after responding with police brutality that left many fallists with criminal records, promised the commission inquiry would fix it all.

It is, for this reason, that the Heher commission’s work was not limited only to tuition fees. It was meant to look at the state of inequality, its costs to individuals and society, the developmental role of and right to education, and what makes it inaccessible to the majority. And what to do about it. Not in a silo of higher education alone, but throughout all of the country and with a justice-minded outlook.

The Heher commission report in this regard was a failure. It did not really engage or respond to the history of how inequality was constructed (and has been allowed to continue). As a result, its recommendations fall short when it comes to the issue of justice, justice for black people, the historical victims of injustice in this country. It was just like the other commissions that came before it that dealt with similar issues, including the Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

Commissions of inquiry in this country have proven (and continue to prove) to be expensive and largely cynical exercises in burying the truth and protecting the powerful, as Dale McKinsey noted of the Marikana Commission.

If you have not had the time, or strength, to go through the tome of a report, we do not blame you. The grand summary is that it proposes free access to TVET colleges, which it notes are largely regarded by students and employers as a second-tier, lower-quality education. One in every three TVET graduate is unemployed, compared to the university graduate unemployment rate of about 5%.

The commission then proposes to do away with NSFAS to access university education in favour of income-contingent loans (ICLs) from commercial banks, backed by government guarantees. It is, effectively, an income-support scheme for commercial banks, providing them customers to whom they would have otherwise never granted credit. A perverse proposal when you consider that many of these banks, such as ABSA, were complicit and benefitted from apartheid, which created the inequalities they now stand to profit from.

ICLs are hailed as the saviours because they allow students to defer repayment until they reach a certain threshold of income and payments continue until the loan is repaid, subject to other terms and conditions. Such as being legally barred from emigrating until the loan is repaid.

However, only the wealthy will be able to opt out of ICLs, which are, in effect, debt bondage, as the price of education. The rest, black people mostly, will be burdened with debt as a result of the historical oppression they have suffered, instead of being offered justice.

The many brave students who put their bodies and futures on the line to make this important call that we engage history and act to undo its unjust outcomes have, therefore, been let down. They have been let down by the commission, by the state and by the leadership at our higher education institutions. They have been let down by their elders, the supposed custodians of history and the guardians of our future.

Gugulethu Mhlungu is a writer, editor and broadcaster on Radio 702, based in Johannesburg. She writes about intersecting structural issues and popular culture through a black feminist lens. Gugulethu has bylines in City Press, Mail & Guardian, Cosmopolitan, Destiny Magazine and Marie Claire.

TO Molefe is an editor and freelance writer, and the coordinator of etc., an on-demand newsroom owned by media professionals.

The views expressed in this article do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of The Daily Vox.