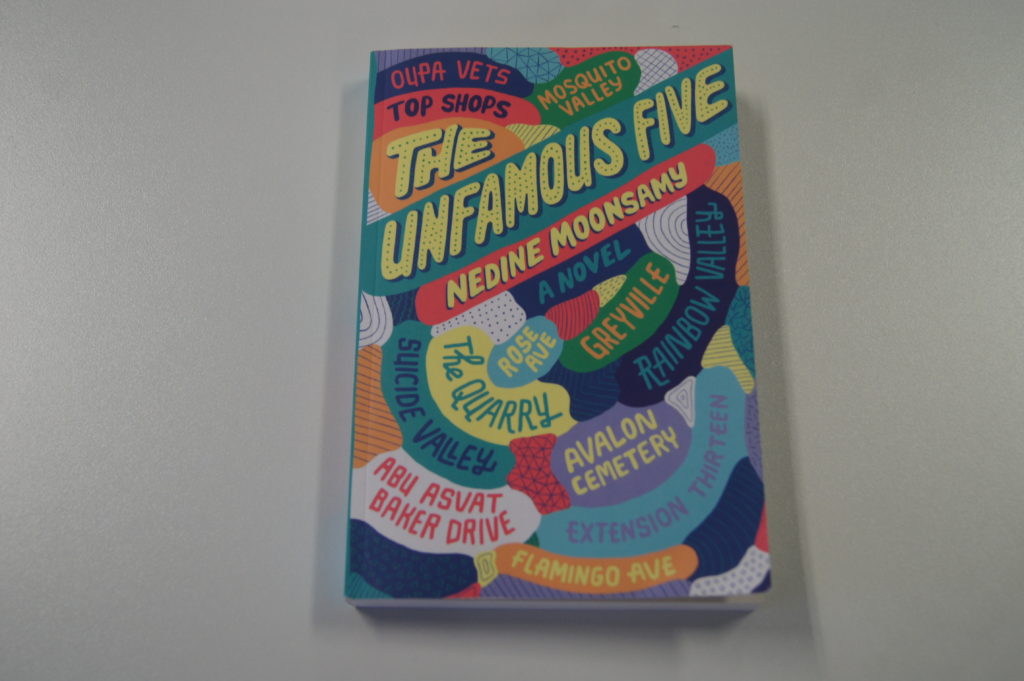

The Unfamous Five by Nedine Moonsamy opens with the five protagonists witnessing a violent crime. This act bounds the friends together and impacts their lives in ways they could never have imagined. Spanning ten years from 1993 and the end of aparthied to 2003 and the dying of the Rainbow Nation, the book is a startling reflection on race, sexuality, class, colourism, religion and identity in South Africa.

The Daily Vox sat down for an interview with Moonsamy about her book. Moonsamy is a lecturer in postcolonial literature, and researcher of contemporary literature and science fiction in South Africa.

The title of Moonsamy’s book is a riff on The Famous Five by Enid Blyton.

In the Enid Blyton series, Moonsamy says, the stories end on a heroic note after the famous five solve a mystery. However, in a contemporary South African context, Moonsamy said crime often isn’t solved so she wanted to explore the lingering trauma and unresolved agony that accompanies unsolved crimes.

This might make the book seem like it is a mystery of sorts. It even feels like the movie “I Know What You Did Last Summer”. The book isn’t anything like that. Instead, it aims to tell the story of Lenasia. More commonly known as “Lenz”, the area was classified a Indian township during apartheid. While it has evolved since apartheid, many of the racial and cultural dynamics remain. Moonsamy, who grew up in Mosquito Valley in Lenasia, said she wanted to represent the people of Lenasia – in terms of how they live, talk and who they are. She also wanted to reflect on Indian South Africans in terms of how they fit in with contemporary South Africans.

But it’s not just the title with which Moonsamy plays with readers’ expectations. In a “coming out” scene, where you would expect all manner of drama, she sought to do something different. By writing it as a kind of calm and subtle scene, Moonsamy said she wanted to “suck the drama out of the scene”.

With the book she aims to question this social mobility and what is being lost in this move in terms of memory.

South African Indians have always occupied an interesting place in South African history. During apartheid, they were classified as black and subjected to apartheid laws. However, this was to a much lesser degree than black people during the system. In post-apartheid South Africa, Indian South Africans have sometimes been accused of trying to replicate whiteness in how they interact with black South Africans. This has caused many tensions, especially on an economic level.

Moonsamy teases this out and speaks to many of these tensions in the book. More interestingly though and something which isn’t as commonly known, Moonsamy shines a light on the tensions that exist within the South African Indian community.

From the outside the South African Indian community could be seen as a homogenous group of people. However, Moonsamy shows that there are in fact many class and linguistic differences that exist. The five main characters all live in Lenasia during apartheid. However, one of the characters, Janine lives in the “poorer” part of town. She is also seen as different because she has darker skin. Later in the novel, another character is made fun of because he has a Durban South African Indian accent. These little things display these differences and serve as a window in the multi-faceted community.

“I mean, we all think we’re special or breaking with tradition to do things for ourselves, but it’s all just part of a pattern. A system that makes us think that we’re all going it differently,” remarks one of the characters.

It’s an interesting statement that encapsulates some of what the book means.

It tells the story of the life of a group of five people that becomes intertwined by the horrible murder. They work their entire lives to carve out a new path for themselves – away from their families, roots and even Lenasia. However, the books end with the five moving back to Lenasia. Their lives are quite different from their parents. They’ve formed a different idea of a family which consists of friends rather than blood relations. But it seems they’ve still replicated some of the pain from their families.

Above all the book shows the lasting power of the generational trauma and disbelonging and what difficult work it can be to unlearn and undo.